Protecting Against Concussions: Helmet Research

(Inside Science) -- This is the third post in an occasional series covering the latest science and news surrounding athletic brain injuries.

Researchers in many fields are working to develop helmets and devices that will protect athletes against concussions, especially in youth, college, and NFL football. But it's also a complicated area of research.

I'll start by pointing readers to this story from the Washington Post. It may have been written for kids, but it's still an excellent primer on what causes concussions.

The common analogy used to describe how a football helmet protects the head is that it's kind of like protecting the shell of an egg. You might be able to envelop the shell with a device that would prevent the shell from cracking after an impact, but that device wouldn't protect the egg's yolk. Like a yolk, the brain sits within a hard shell, surrounded by fluid. And like a yolk, it can be shaken up.

A study of Wisconsin high school football players found no indication that the brand or age of modern helmets was related to protection against concussion. But researchers are still trying to make improvements to these important pieces of safety equipment.

One popular addition to helmets, which writer Sean Conboy reports that players swear by, is Kevlar, the same material that's used in bulletproof vests. His stories in Wired and Deadspin are both excellent reading. Here's an excerpt from a discussion he had with Dartmouth biomedical engineering expert Richard M. Greenwald, which he shared on Deadspin:

"You're telling me that NFL players are installing Kevlar inside their helmets?" he said, dryly apoplectic. … "I can't think of a single reason why installing Kevlar would protect the brain in a collision," he said. "It's the egg-yolk-inside-the-shell analogy. Making the shell stronger will still scramble the yolk."

Meanwhile, biomechanical engineers at UCLA are working on a thin polymer sheet that would be used to reinforce the padding currently used in helmets, which lead researcher Vijay Gupta found could achieve "up to a 25 percent reduction in the force a person would feel. This translates to a similar reduction in the probability of getting a concussion," the university reported in a statement.

This review of helmets currently on the market, from Athletic Business' Michael Gaio [Editor's note: Link is no longer active.], finds little evidence that new technology is increasing protection against concussions. The story mentions soft helmet caps, which the manufacturers claim can reduce impact forces up to 33 percent (according to this story from the Coloradoan) [Editor's note: Link is no longer active], but also that various regulatory hurdles are keeping them from being used. The comments that accompany Gaio's story are also very interesting.

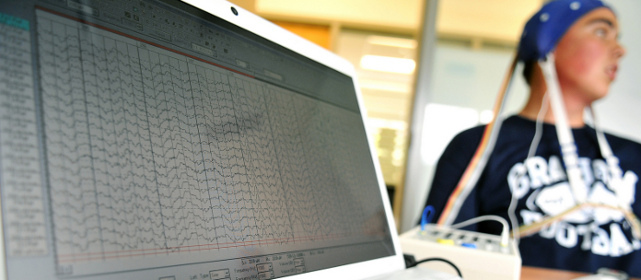

The National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment will not certify modified helmets and released a statement that adding equipment to a helmet in this way voids the certification of the original helmet. This USA Today story covers the helmet caps, and mentions other equipment intended to help monitor impacts, such as devices from helmet manufacturer Riddell, Seattle-based X2 Biosystems, and another from Reebok.

Attempts at innovation aren't limited to helmets and head coverings. This story from Deadspin explains one out-of-the-box idea that might provide help, developed by Dr. Julian Bailes, one of the founders of Brain Injury Research Institute. It's called a jugular vein compression device. In a proof of concept study, Bailes found that placing a ring around a rat's neck gently compresses the internal jugular vein, which in turn increases the amount of blood in the head, and essentially leaves less room for the brain to slosh around after a hit.

It will probably take more research before players are willing to try wearing a human version of one of these one the field, but Dawn Comstock, an injury epidemiologist at The Ohio State University, thinks that another way athletes might protect themselves is by strengthening their necks. She believes the neck acts as a shock absorber, and that the stronger it is, the more it protects against the accelerations and rotations caused by impacts that can lead to concussions, Athletic Business reported.

As research continues, from the NFL to Pee Wee football, groups are making new rules that apply to practice and games, from reducing the duration of full contact practice sessions, to outlawing hits to the head.

The Mayo Clinic is even testing a method to provide assistance to players and trainers that uses a telepresence robot to allow doctors to assess concussions in real time without having to attend a game in person.

But, no matter what precautions are taken, football players remain at risk for concussions. What's the best protocol to follow for those that have already had a concussion? The Journal of Neurotrauma reviewed the guidelines from three major reports and made the following conclusion:

"Key recommendations of all three groups are that any athlete suspected of having a concussion should not be allowed to return to play on the day of the injury, concussed athletes should not return to play until they have been evaluated by a licensed healthcare provider, and even then there should be a gradual, stepwise increase in physical activity."

In David Epstein's recent book, "The Sports Gene," he describes research that demonstrates a genetic element to concussion risk. He explains that a gene called ApoE seems to be related to brain injury and also Alzheimer's disease risk. People carry two copies, inherited from their father and mother, and if one of them is a variety known as ApoE4, the risk of Alzheimer's is increased three-fold. If both copies are ApoE4, the risk is eight times higher. Epstein wrote that one researcher told him the risk of dementia for people with "a single ApoE4 copy is roughly similar to the risk from playing in the NFL, and that the two together are even more dangerous."

NFL teams have reported at least 64 concussions through the preseason and the second week of the regular season. Teams and the league will continue to pay attention to the issue, as will scientists, equipment manufacturers and others. I'll continue to follow the research for Inside Science Currents.

Previous Currents Blogs on Concussions:

Concussions: Lots Of Ink, More To Come

Protecting Against Concussions in Football and Beyond