A Chimp's Point Of View

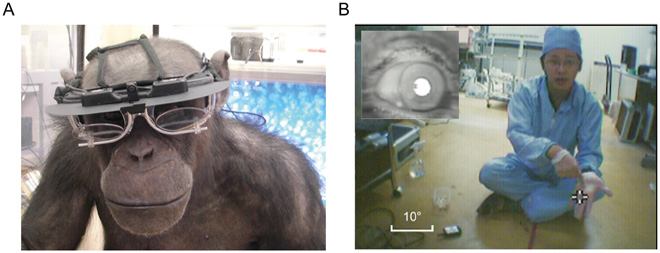

Goggles simultaneously monitor a chimpanzee's eyes and field of view.

Image

These two images show chimpanzee Pan wearing an eye-tracking system on her head (A) and also a picture from the outward-facing camera on Pan's headset (B). The cross mark in the lower-right corner shows where Pan's gaze is directed.

Media credits

Fumihiro Kano and Masaki Tomonaga | http://bit.ly/17riq0m

(ISNS) -- Chimps with camera goggles on their heads are helping scientists learn how the apes literally see the world.

From a scientific perspective, the eyes are windows to the mind. What people watch is one key sign of what they might be thinking, so monitoring their gazes can help researchers learn about what is going on inside people's heads.

Scientists have conducted eye-tracking studies on people for more than 100 years. However, comparably little work has been conducted with other primates. Such work promises to shed light on humanity's closest living relatives, and how they might perceive the world differently.

"If we know the differences between chimpanzees and humans, we will have an insight into how human perception has evolved," said comparative psychologist Fumihiro Kano at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Until recently, eye-tracking research involved desk-sized machines confined to labs. Investigators now have access to portable, wearable eye-trackers, enabling scientists to learn how people look at and interact with the world in a more natural way. This enables them to research topics such as how experts look at the world differently from novices. Now Kano and his colleagues are using these devices to study chimps.

"Everybody wants to see the world through chimpanzee eyes, right?" Kano said. "That's one of my childhood dreams. How do chimpanzees, the closest relatives of humans, see the world?"

The researchers placed lightweight goggles on a 27-year-old female chimpanzee named Pan that had one camera monitor her right eye and another aimed at her field of view, both of which sent data to a portable recorder. The mobile setup allowed the chimp to move and behave freely.

"We modified the eye-tracker goggle shape so that the chimpanzee could wear it and like it," Kano said. "If the chimpanzee felt uncomfortable wearing the goggles, she wouldn't care about throwing it away!"

When Pan wore the eye-trackers, the scientists practiced a two-minute gestural task with her that she had already learned for several years. The researchers performed one of three gestures — touching their noses, touching their palms, or clapping their hands — and gave Pan pieces of apple from a transparent box as a reward whenever she copied that task. The goggles also captured the greetings Pan often gave people before tasks, such as pant-grunting or swaying.

"No researcher has been successful in recording the natural gaze of chimpanzees before," Kano said.

The researchers found out how Pan looked at the world differently depending on what she was doing. For instance, when greeting experimenters, the chimpanzee focused on their faces and feet — the latter presumably to see where they were going — but during the gestural task, she gazed at the experimenters' faces and hands. In addition, while Pan mostly ignored the fruit reward before the gestural task, she looked at it 30 times more during the task. Kano indicated that this focus on the fruit reveals that Pan was thinking ahead to anticipate the future.

"This work builds toward an understanding not just of how chimpanzees learn about the world, but how they want to influence it," said neuroethologist Stephen Shepherd at Rockefeller University in New York, who did not take part in this research. "We can use gaze as a readout of what chimpanzees think is important to attend and affect."

Moreover, past research with desk-mounted eye-trackers hinted chimps did not look at familiar faces any longer than unfamiliar ones, but these new findings suggest otherwise — Pan looked at unfamiliar experimenters longer than familiar ones.

The researchers think one reason for the difference may have been because the previous studies used pictures of faces, shown for a shorter amount of time. In the new experiment, Pan also looked at familiar people longer if they were not in rooms where she was accustomed to seeing them.

The researchers plan on testing more chimpanzees with these wearable eye-trackers. They also want to compare the apes with people and other primates.

"It will be very interesting to see how humans, chimpanzees and other primates use gaze while performing the same real-world tasks," Shepherd said. "I would love to know if chimpanzees are intermediate between humans and monkeys, or if they're just like humans."

In addition, future research will analyze how chimpanzees predict the actions of people and other chimpanzees. How the apes predict the actions of others in real-time, "that is, within a fraction of a second, is largely unknown," Kano said.

Kano and his colleague Masaki Tomonaga detailed their findings online March 27 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Filed under