How Musicians Prevent Chaos In A String Quartet

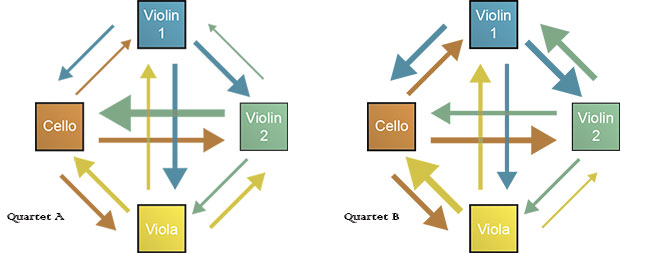

This diagram shows how musicians adjust to each other: The arrow width denotes the influence one player (arrow tail) has over another (arrow head). Researchers deemed quartet A a first-violin-led autocracy, and quartet B a democracy.

courtesy of Alan Wing

(ISNS) — When a classical string quartet starts playing, someone starts them off with a downbeat. Then it's every man or woman for themselves.

But good string quartets seem to keep perfect time, playing each note at just the right beat, blending in and out just as the composer wished, seemingly in perfect unity. How do they do that without a conductor?

A team of scientists and musicians from the United Kingdom and Germany wired two world-class string quartets with microphones plugged into computers running the same kind of program that Wall Street traders use to buy stocks and climatologists use to track and measure atmospheric changes in real time.

They found the musicians used two forms of coordination, but in both cases, they were altering their playing in degrees measured in milliseconds without any verbal or physical help, even modifying what they were playing if one of them changes the tempo.

"In some other music, people just come and play together, but in a string quartet, like any ensemble, have to become one organism," said Alan Wing, a professor of psychology at the University of Birmingham, England. "It's remarkable."

A string quartet classically consists of two violins — a first and second — a viola and a cello. Traditionally, the first violinist is the team captain — often called "The Leader" — but in recent years, quartets have become more democratic with no one leader.

It depends largely on the sociology of the group, said Adrian Bradbury, a professional cellist who has played with such orchestras as the Royal Philharmonic in London and a member of the research team.

In their study, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, the researchers wired two world-class quartets and had them play 48 beats of music from the opening of Franz Joseph Haydn's Quartet Op. 74 No.1's fourth movement. One of the quartets used the first violinist as leader, the other had no set leader.

To add uncertainty into the playing, the researchers told one or another musician to make a subtle change in the tempo to see what the other three would do, Wing said.

Then the results were fed into a computer that was running a similar program that Wall Street traders use to track stock prices and make instantaneous buying or selling decisions. Essentially, it measures the effect of one stream of data against another over time.

When any of the musicians altered the tempo the researchers looked to the next beat. Followers would have made the adjustment. Just by watching which player adjusted to whom, the researchers were able to tell which group member was following and which was leading.

In the quartet led by the first violin, the other three made their adjustments depending on what the leader was doing. Rarely did the leader adjust to them. In the more democratic ensemble, they all adjusted to each other.

Bradbury pointed out that many quartets play together for years — quartets that have been together for 40 or more are not unusual — and these kinds of seamless adjustments come naturally and without the audience ever noticing.

"You want the audience to take in information without being explicit," Bradbury said.

At rehearsals, the quartet is merely making sure they know the music well enough so that if one member varies, the ensemble follows, he said. Even in chamber music where the notes and the timing commands are clear, musicians will vary qualities such as the tempo as they express emotion. Without that spontaneity, the music would be dead, Wing said.

Michael Kannen, a cellist and one of the founding members of the Brentano String Quartet said he wasn't surprised. Good musicians do not really need a conductor; even full symphony orchestras can play well without them. Great conductors bring interpretation and shape the piece. The musicians can time themselves.

In rock groups, the musicians play off the drummer; in jazz bands, they get their timing from the rhythm section, Kannen said.

Most of the time, the first violin is playing the melody, the cello is playing the bass line, and everyone else is doing the inner voices or the rhythm, but it is constantly shifting, he said.

"Musicians play with their ears, not their eyes," Kannen said. "It's like any sport or amazing feat," he said. "Once you develop the skill it doesn't seem so hard anymore."