Satellite Data Helps Predict Meningitis Outbreaks

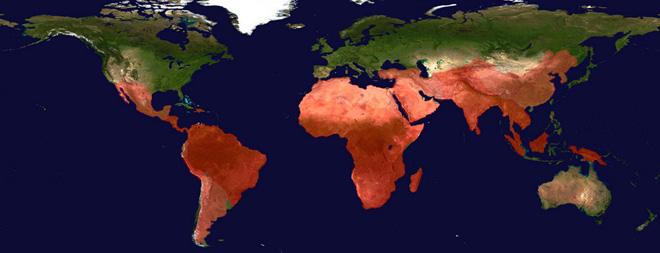

Composite map displaying global distribution of malaria, whose prevalence varies with climate conditions, with most affected areas shown in deepest red.

Genome Research Limited | http://www.sanger.ac.uk/about/history/achievements.html

(Inside Science) -- Researchers are combining satellite and land-based data in new methods to help healthcare workers prepare for climate-related disease outbreaks.

The infectiousness of many diseases, such as those carried by insects and microbes, varies with environmental conditions. Predicting outbreaks of these diseases is difficult enough, but with global climate change shaking up the Earth in unknown ways, that task is becoming even more difficult.

Pietro Ceccato, a research scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University in New York, said that in Africa, land-based environmental monitoring stations are few and far between -- so it's much easier to grab data from passing satellites and interpret it.

"By monitoring satellite data, we hope to forecast epidemics 1-2 months ahead of time," Ceccato said. "Eventually we'd like to integrate climate information into vulnerability for all kinds of diseases."

The group started by looking at two illnesses: malaria and meningitis. Both are related to environmental factors -- malaria is linked to high precipitation and temperatures that allow mosquitoes to thrive, while meningitis is connected to dry and dusty conditions in deserts.

Ceccato and his colleagues have built tools that provide information on when dusty conditions are likely to crop up in Africa. They integrate the data coming from satellites into Google Earth or NASA's SERVIR to help ministries of health in different countries know when and where to send their supplies of meningitis vaccine. The information is presented in an easy-to-use way, Ceccato said.

Meningitis prediction is a relatively new field, and researchers are honing their efforts in the Sahel region of Africa, which extends from Senegal to Ethiopia. This area, which is south of the Sahara desert, has the greatest incidence of the disease, said Ceccato. For reasons that aren't entirely clear, outbreaks of bacterial meningitis appear to favor the dry, dusty conditions common from November to April across this semiarid region, known as the African meningitis belt. The region's last major meningitis epidemic, in 1996, generated at least 200,000 cases of the disease and killed thousands.

Researchers believe that environmental factors may play an important role in the occurrence of the disease -- and so they turn to the skies for information. The satellite sensors can interpret the level of dust in the air based on colors, and the model builds a pattern of dust every three hours over the Sahel.

There is a meningitis vaccine, said Ceccato, but since there isn't enough of it to supply every vulnerable country, it's vital to target the regions with the highest risk. He works with public health ministries in Madagascar, Eritrea and other places to make them aware of where and when high-risk areas will pop up.

Ceccato's sentiments are echoed by other researchers working on new ways to harness earth science data to forecast disease. Rajul Pandya of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., said that the newest vaccine only works against one strain of meningitis -- but that when humidity rises, the epidemics start to disappear.

"Once the humidity exceeds 40 percent, the epidemics decrease significantly," Pandya said.

Pandya and his colleagues are working on a method to create 14-day forecasts of atmospheric conditions like humidity across the meningitis belt, using a number of computer models as well as satellite data. The forecasts can detect patterns in the upper atmosphere that correlate with higher humidity and the impending start of the rainy season, which tends to advance from south to north.

Ceccato explained that satellite monitoring can also give countries a good checkup on how well they are responding to climate-related disease, by letting them know which years are dry (and so may have more meningitis) and which are wetter (and may produce more malaria-bearing mosquitoes).

"We are all going to have to adapt to climate change for health," Ceccato said.

Ceccato and his team hope to expand the effort to other data-poor regions of the globe such as Latin America and Asia, as well as expand the number of diseases they can monitor from on high.

The research was presented at this month's meeting of the American Geophysical Union.