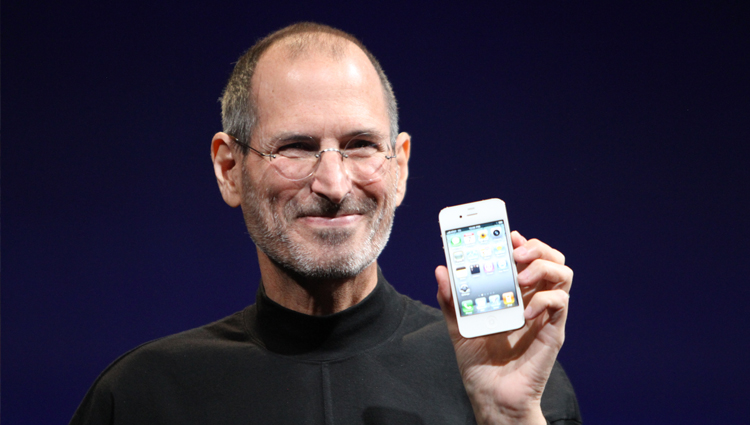

Steve Jobs: From an Appliance to Cool, United by One Philosophy

Image credit: Matthew Yohe via Wikimedia Commons

(Inside Science) -- The deaths of CEOs rarely touch as many people as the sudden announcement that Steve Jobs had died on Wednesday.

We all know his story. Jobs founded Apple, commercialized the personal computer, and introduced graphic displays that made computers accessible to everyone.

Fired by Apple in 1985, he bought a failing computer animation company. Nine years later, Pixar rewarded him with "Toy Story."

After returning to Apple, he launched the iPod, iPhone, and iPad. All three were really portable computers, and they changed how people consumed music, books, and movies.

Other companies had pioneered these products before Jobs. Yet in nearly every case, he pulled off what appeared to be magic tricks: He used technology to make technology disappear. What remained was a playfulness that gave rise to sheer delight for so many users.

A modern oven probably has more processing power than early Macintosh computers. Yet many consumers found Macs a revelation.

They were expensive ($5,000 in today's dollars), underpowered, and did not run many popular software titles. But they created a growing legion of enthusiasts by tempting them to play in ways they never imagined.

Years later, millions had the same reaction to the iPod. Many had listened to MP3 players before, but they couldn't keep their hands off the iPod. They skipped from song to song, sharing headphones. The iPhone evoked even greater wonder.

Jobs made products that people wanted to touch. Several years ago, Donald Norman, author of the seminal book, "The Design of Everyday Things," and an Apple fellow in the mid-1990s recalled, "When I was there, they were creating things that were so beautiful, our first reaction was, 'Wow, that's cool. I want it.' Our next response was, 'What is it?' Then we would ask, 'How much does it cost?'"

How did Jobs do it? Remember, this very same epitome of cool who created the iPhone also spent years talking about his Macintosh as an appliance. Yet the same philosophy underlay both.

Jobs called the Mac an appliance because, like a refrigerator or washing machine, you didn't need to know much to use it. In a world where PC users had to memorize and type commands, Macs let people point and click.

Better yet, everything worked together. You could draw something in MacPaint and paste it into MacWrite. Each application had a similar look and feel, which made them easier to learn and even fun. And you could always experiment by clicking buttons.

Starting with the Macintosh, Jobs used technology to create interfaces so simple and intuitive, anyone could figure them out. If child is father to the man, than Mac is father to iPod, iPhone, and iPad.

Chris Hammond, a designer, once noted that electronic products had complex interfaces because marketers wanted to add features to differentiate them from the competition.

Jobs went the other way. His interfaces differentiated his products, even at the expense of features.

"Think about Apple's iPhone," Hammond said. "You can access all those features and never use a single drop-down menu. Now think about the clunky interfaces on your TV and VCR."

Equally important, Jobs' designs went beyond the product to encompass the entire user experience. iTunes is an example. It made it easy for even computer illiterates to buy, download, and manage hundreds or thousands of songs. Its introduction turned a nice piece of hardware into a phenomenon.

Jobs pulled off a similar coup with his iPhone, demanding total design control, network upgrades, and even a faster store sign-up process before he would let AT&T Wireless sell it. He negotiated deals with music, movie, and book publishers to give users easy access to content.

Jobs always understood what he was selling, and had no qualms enforcing his sensibility on Apple. A case in point occurred just he introduced the iPad. Another reporter, perhaps skeptical of its utility, asked Jobs how much consumer and market research went into it.

"None," Jobs replied. "It isn't the consumers' job to know what they want."

Most corporate leaders would cover their back with reams of studies and analyses. But Jobs trusted his instincts. Sometimes they led to disaster (remember the Lisa or Apple III recalls?). More often, though, the sense of play his devices embodied was simply too infectious to ignore.

With Jobs' death, some worry that Apple will become less innovative.

Yet his influence extends far beyond any one company. Anyone who picks up an Android phone, opens a Microsoft Windows 7 laptop, or downloads music from Amazon, is meeting one of Steve Jobs' ubiquitous children.

Alan S. Brown is a long-time freelance writer who has written extensively about science, engineering, technology-related businesses, and technology policy.