Stray Wireless Signals Power Battery-Free Devices

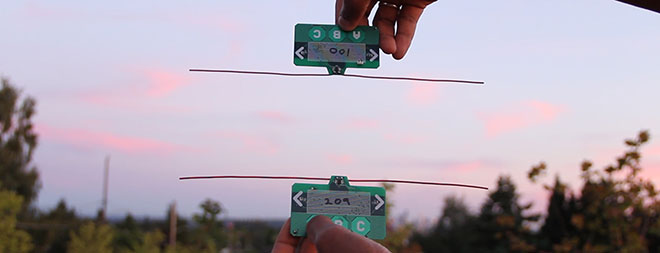

Researchers demonstrate how one payment card can transfer funds to another card by leveraging the existing wireless signals around them.

Image credits: Courtesy of the University of Washington

(Inside Science) -- In Shyamnath Gollakota’s dream world, every object can talk to every other object, which is particularly useful if you have misplaced your keys.

Imagine that your keys dropped out of your pocket and fell between the cushions of a couch. You ask your cellphone to find them. The keys tell the couch where they are, and the couch relays the information to your cellphone. If you also have misplaced your cellphone, your computer will find them both.

The transmitters for all this information are minuscule because they do not require outside power--no batteries, no wires plugged into a socket. They draw their power seemingly out of thin air.

The devices, developed by Gollakota and his colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle, make use of ambient backscatter -- converting the electromagnetic waves that surround us, from television broadcasts to cellular signals, into the power necessary to send the 1s and 0s of computer language.

“It does not generate a signal of its own and operates without a power infrastructure,” Gollakota said.

They reported their work at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Data Communication conference in Hong Kong last week, where it won the award for best paper.

Gollakota’s world has been tested on a small scale. Consider walking into a supermarket, picking up a can of soup, and deciding while shopping later that you did not want the soup after all and then put it back on the wrong shelf. Happens all the time. The Washington researchers tested a system in a store in which the soup can talks to neighboring cans, decides it is in the wrong place, and tells the humans so it can be moved.

The researchers also devised a new kind of smart credit card. If you press it in the right place, it will transfer money to another card in the vicinity. No paper, no batteries, no fuss.

Did your cell phone run out of battery power? You can still text from it using an ambient backscatter chip.

Paul Saffo, a futurist and managing director of foresight at Discern Analytics and who teaches at Stanford, calls these devices “smartifacts.” He described Gollakota’s world one in which “everything has a rudimentary intelligence and an ability to account for itself.”

To understand how it works, think of the transponder in many cars that automatically pays tolls when you drive through a tollbooth. That transponder has no power itself but the reader in the tollbooth is plugged into an electric source, and it sends out a signal that triggers the transponder to send back an identification code. A computer takes the information, and you are billed. That is called Radio Frequency Identification, or RFID.

Large stores use similar technology to keep track of what’s on the shelves.

The Washington researchers have a similar system, but their devices are not plugged in, and they don’t need batteries, so they are cheaper, smaller, and last much longer.

The energy comes from wireless signals, such as from a TV or cellphone tower, which all transmit electromagnetic energy. The transmissions stimulate the movement of electrons in the devices’ circuits, which can be harvested as electrical energy, Gollakota said.

An antenna in the device switches between reflecting and not reflecting the wireless signals. When it reflects a signal, it is sending out the analog to a 1. When it is not reflecting a signal, it transmits the equivalent of a 0.

The budding technology has serious limitations. First of all, it is extremely slow; one kilobit per second when the devices are 2.5 feet apart--so essentially it is sending out something similar to Morse code. So far, the devices have to stay within several feet of each other.

In principle, Gollakota said, the devices can transmit as fast as 600 kilobits to 1 megabit, enough for low-definition video.

Getting rid of batteries was a “really big deal,” Saffo said. “They are too expensive and too toxic.”

Saffo said one of the criticisms of the research was that it wouldn’t work in the developing world which is not suffused with wireless signals. He said the solution to that was simple: just put up a few small radio transmitters.

Saffo, who called the experiment “cool,” added that the concept was not new. He once did an industrial show when he was a consultant that involved Coke cans talking to refrigerators. The work of Gollakota and his colleagues could make that possible for everyone.