Why You Should Probably Get a COVID-19 Vaccine Even if You've Already Had the Disease

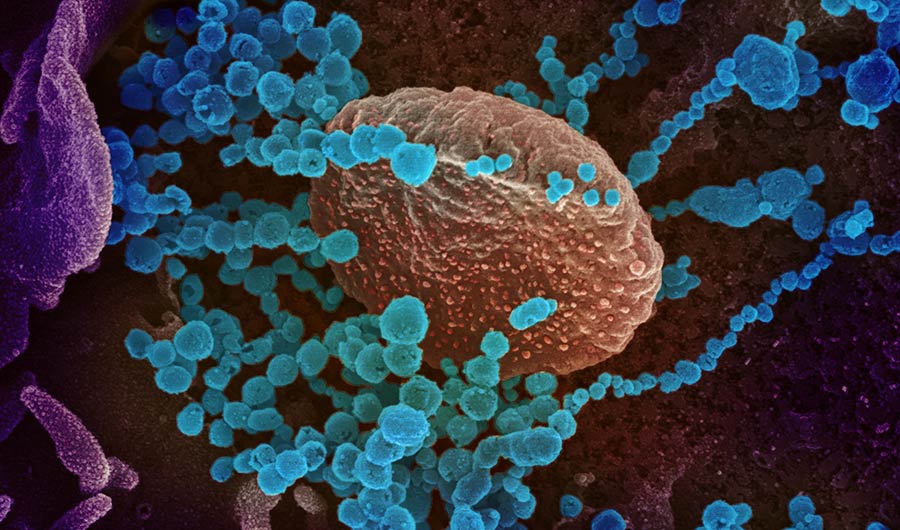

A scanning electron microscope image showing SARS-CoV-2 virus (blue dots) emerging from cells cultured in the lab.

NIH Image Gallery via Flickr

Public Domain Mark 1.0

(Inside Science) -- COVID-19 vaccines could provide stronger, longer-lasting immunity than recovering from the disease itself, say experts.

Most people who recover from COVID-19 probably enjoy some degree of protection against getting the disease again. Both the strength of that protection and how long it lasts remain open questions, with the answers complicated by a mixture of conflicting evidence. Some studies suggest the virus that causes COVID-19 may interfere with immune memory, leaving people vulnerable to repeat infections months or years later.

But even if that's true, there is no reason to think vaccines, once approved and available, would suffer from the same limitations.

"We're thinking that with the vaccines, we should be able to do better than nature," said Peter Doherty, a Nobel Prize-winning immunologist at the University of Melbourne's Doherty Institute in Australia.

More COVID-19 reporting from Inside Science

How Nobel-Winning Research is Helping Battle Covid-19

Fighting Misinformation About a Novel Disease

Disgust Evolved To Protect Us From Disease. Is It Working?

How the immune system remembers COVID-19

There are several ways the immune system can "remember" a virus after an infection has been vanquished. One involves B cells, which produce the virus-busting structures known as antibodies. Some B cells continue to produce antibodies even after an infection clears, while others linger in a dormant state until they are reactivated. Another type of immune memory involves killer T cells, which attack human cells that have been infected and turned into virus factories. Killer T cells reach their highest concentrations during infection, but a small population may remain for decades, ready to launch a faster response next time.

New research that is not yet peer reviewed indicates B cell and T cell immunity may remain strong six months after infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But it's not clear how much longer that protection will last, and there are other studies suggesting that both types of immune memory may be impaired by the disease.

"What this virus is doing is in some way compromising aspects of our immune response," said Doherty. "We do think long-term immunity following infection is problematic."

In a study published last month in the journal Cell, researchers examined the lymph nodes of people who had died of COVID-19 and found they lacked structures called germinal centers. Germinal centers are where B cells mature into long-lived forms that produce better antibodies -- antibodies customized to bind strongly to a specific enemy. The process is similar to Darwinian natural selection, with B cells going through repeated rounds of genetic mutation. Mutated B cells that produce better antibodies are sent back to mutate again; B cells that produce worse antibodies die.

While the body can produce effective B cells without germinal centers, those B cells tend not to last as long as ones that have been through the germinal center process, said Shiv Pillai, director of the Immunology Graduate Program at Harvard Medical School, who conducted the study with his colleagues. If COVID-19 prevents people from forming germinal centers, said Pillai, that could mean people can only produce antibodies for a limited time after infection.

The researchers could only examine lymph nodes from deceased people, so the germinal center problem might only crop up when illness is severe, noted Godelieve de Bree, an internist and infectious disease specialist at Amsterdam University Medical Centers in the Netherlands, who is studying COVID-19 antibodies. Immunologist Michel Nussenzweig at Rockefeller University in New York agreed, saying that findings from deceased patients do not necessarily indicate anything about people who recover.

"I think you see a problem with everything in people [who] are dying," said Nussenzweig.

Further evidence leads to conflicting interpretations. Pillai noted that antibodies collected from COVID-19 patients during and soon after infection have few of the telltale mutations that would indicate they have been through germinal centers. That's true regardless of the severity of illness, suggesting that immune memory from B cells may be limited even in mild and moderate cases, according to Pillai. But Nussenzweig's team recently found evidence that mutation levels are higher six months after infection, suggesting that long-lived B cells may develop gradually after people are well.

There are also hints that killer T cells may be impaired by COVID-19. In a study published in September in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by Katherine Kedzierska at the Doherty Institute found that killer T cell counts in COVID-19 patients didn't rise nearly as much as the researchers expected, and there was no sign that any remained after recovery to provide immune memory. Even at the height of infection, there were only a tenth as many killer T cells for the COVID-19 virus as a typical person has left over from influenza A infections sometime in the past.

"The killer T cell system in this virus seems to be compromised. It's not as good as it should be," said Doherty, who also took part in the study. He added that the study only looked at one of several types of killer T cells involved in COVID-19, and more research is needed.

So how long can people who recover from COVID-19 expect to be protected? It's still unclear, and opinions are divided. Pillai suspects most COVID-19 patients will lose any protection they gained from B cells and antibodies within a year of recovery, and potentially sooner. De Bree thinks immunity may last around a year, as that's how long it lasts in other coronaviruses that cause seasonal colds.

It's now clear that reinfections can happen. As of Nov. 11, there are 421 suspected and 25 confirmed cases of people being infected twice, according to a tracker maintained by the Dutch news organization BNO News. In most cases, the second illness has been mild or asymptomatic, but one man in Nevada came down with severe COVID-19 barely more than a month after recovering from a milder version.

Nussenzweig noted that those reinfection numbers are low, considering the millions of people who have been infected. But with the pandemic less than a year old, it is still early days.

"I think it would be very important not to depend on getting immunity from being infected," said Pillai.

Why a vaccine could be better than nature

If it turns out that COVID-19 does leave people vulnerable after recovery, why should researchers expect a vaccine to provide longer-lasting protection?

A few decades ago, they might not have. For diseases like measles, mumps and hepatitis B, all a vaccine has to do is mimic nature, since people naturally develop lifelong immunity after infection. But many viruses avoid or manipulate the immune system in ways that leave people open to repeat infections. Modern vaccine development aims to correct for such problems.

"Our goal in this case is to definitely do better than natural immunity," said Barney Graham, deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Graham helped isolate and stabilize the viral spike protein that is being used in many COVID-19 vaccine candidates, including the vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech that made headlines on Monday after the companies announced promising early results from a clinical trial. Graham's team is now collaborating with the biotechnology company Moderna on another COVID-19 vaccine candidate.

One example of a vaccine that typically provides better immunity than a natural infection is the HPV vaccine, which protects against strains of human papillomavirus that cause cervical cancer. HPV spends most of its time hiding inside cells of the skin and the lining of the cervix without doing anything to draw the attention of the immune system, said Richard Schlegel, a virologist and pathologist at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, who helped develop the vaccine in the 2000s.

In contrast, vaccination involves injecting viral proteins directly into the muscle, and from there the proteins spread throughout the body -- a challenge the immune system can't ignore. Afterward, the trained immune cells can recognize HPV proteins wherever they crop up, even in the tiny quantities produced by natural infections.

COVID-19 presents a different set of challenges, including the possibility that the virus may be thwarting aspects of the immune system’s memory. A vaccine may be able to get around this, researchers say.

Many of the vaccine candidates don’t use the whole virus, delivering instead a single viral protein or protein fragment to stimulate the immune system. Some vaccines deliver the protein directly, while others deliver a gene that induces the body to produce the protein in its own cells. Researchers might not understand exactly how SARS-CoV-2 manipulates the immune system, but it likely takes more than a single protein.

"We're taking away all those other viral genes that are probably screwing up the immune response," said Doherty.

Many vaccines also include substances called adjuvants that enhance the immune response and guide it in certain directions, said Graham. And in some cases, vaccines can be delivered in multiple doses to further boost their effects.

Even with such advantages, a COVID-19 vaccine probably won't make people completely immune for the rest of their lives. Graham expects vaccinated people will still be susceptible to infection, but will fight off such infections quickly, hopefully before feeling sick. Some people will probably still transmit the virus to others, but not as often. People may also need yearly booster shots.

That may not sound like the magic bullet some people are hoping for. But if a vaccine can be proven safe and effective and made widely available, it could offer a path forward, out of a crisis that is still crippling economies and killing thousands of people around the world each day.

"Everything is telling us, if you want to be protected, whether you got infected or not -- please, get vaccinated," said Pillai.