Bacterial Bullet Takes Aim at Red Tides

Bloom of Karenia brevis, also known as Florida red tide.

P.Schmidt, Charlotte Sun

(Inside Science) -- Harmful algal blooms are a rising threat worldwide, triggered when colonies of microscopic plants grow out of control. As the algae that cause these blooms multiply, they clog the water and use up all the oxygen. The toxins they release, tossed into the air by waves, make it hurt to breathe. Oysters and clams that filter their food from affected water become unsafe to eat. Beachgoers take a look and a sniff and turn on their heels.

Now, University of Delaware researchers are using algae-killing bacteria, packaged in what they call “bacterial bullets,” to target the small, simple plants known as dinoflagellates that are responsible for many harmful algal blooms.

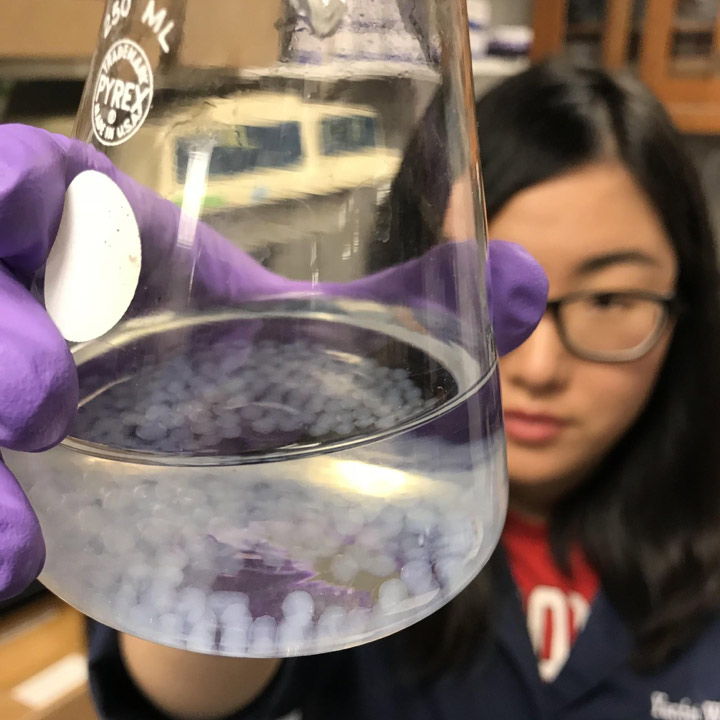

The “bullets” are made from a common industrial ingredient called alginate. Mixed into food, medicine and cosmetics, alginate gives products a smooth texture. Kathryn Coyne, the marine biochemist who led the project, had the idea to incorporate bacteria-laced water into a batch of alginate. The resulting gel could be shaped into small spheres reminiscent of tapioca pearls.

“By embedding bacteria into these gel beads and deploying them in risky areas, we could treat existing outbreaks and stop new ones from happening,” she said. Concentrating the bacteria in the beads magnifies their potency.

A visiting scientist unknowingly launched this project when he stored away a hodgepodge of bacterial samples from the bays surrounding the University of Delaware. For almost 20 years, those cultures sat frozen. Then, graduate student Clinton Hare, who was interested in natural chemicals called algicides -- which kill algae -- thawed a vial of the bacteria Shewanella and began testing them on dinoflagellates.

Shewanella releases a chemical that kills dinoflagellates, seemingly without harming other marine life. Coyne and her team exposed fish, crabs, plankton and larger seaweeds to the bacteria with no ill effect. She now thinks that Shewanalla is targeting a vulnerability in the way dinoflagellates organize their genetic material.

“Dinoflagellates are really interesting because they have this unique way of packaging their chromosomes in their nucleus,” said Coyne. “So whatever these algicidal compounds are, they just cause the chromosomes to unravel. It’s really quite striking.”

Dinoflagellates cause red tides throughout the world, and research has shown that Shewanella is common in both oceans and freshwater environments. Coyne herself carried out a thorough search in the bays of Delaware and said she was able to find the bacteria almost everywhere she looked.

The bacteria’s ubiquity may mean it can be used in other places with blooms caused by dinoflagellates. Florida, for example, experiences an intense annual bloom caused by a different dinoflagellate species. But like all its cousins, it contains that same genetic vulnerability encoded in its DNA.

Raphael Kudela, a plankton ecologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz who was not involved in this research, counts this project among several creative approaches to treat red tides.

“There have been efforts to do similar things before, but they were either too specific or they were bad for the environment,” he said. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tracks blooms across all 50 states, and research is projecting an increase in harmful blooms worldwide for both freshwater and marine systems as temperatures and nutrient runoff rise.

Coyne and Kudela both emphasize responsibility when using a living control like bacteria. It’s why Coyne needed to be sure Shewanella targeted only dinoflagellates and why she verified its presence throughout Delaware. Spreading bacteria loosely within the water could work well in theory, but it cannot be undone. The beads, deployed in grocery-sized mesh bags, hold the bacteria in place while they release their algicidal chemical into the surrounding water. Once the bloom has dissipated, the beads are removed.

“This bacteria is something you can already find in the environment, something we can use to address human health concerns and stop fisheries collapse,” Kudela said. “And the way they are proposing to use it is removable, so if you don’t like what it’s doing you can always take it out.”