Fighting ISIS and Fake Facebook Accounts with Physics

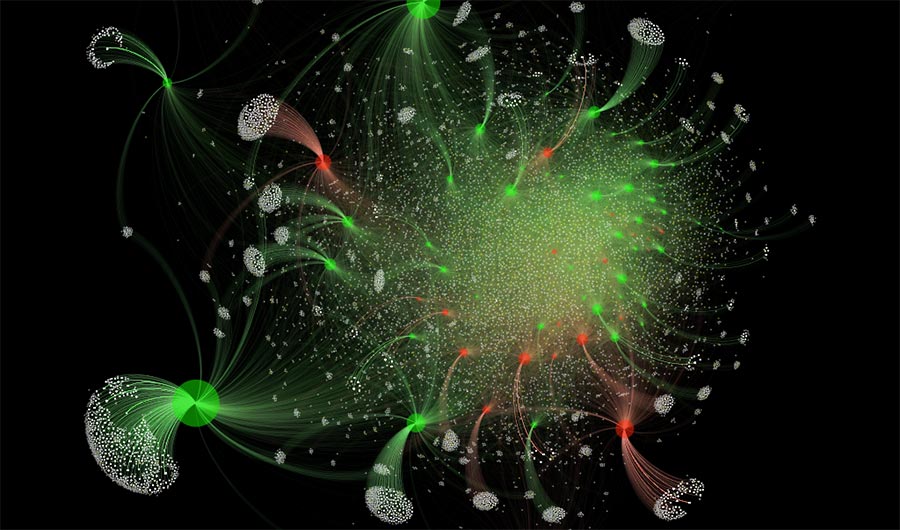

This graphic represents an online web of extremism and hate on social media (e.g. in support of ISIS) showing how individuals ‘gel’ together around particular extremist ideas and topics on a given day. Black dots represent pockets of extremism/hate, white dots are online users whose connections are shown as red links.

N. Johnson, P. Manrique and M. Zheng

(Inside Science) -- In late 2014 and early 2015, pro-ISIS groups proliferated on VKontakte, a Russian online social network. Within months of their founding, the groups had amassed more than a hundred thousand members -- including at least one who would lead ISIS fighters in Syria.

The emergence of these groups, seemingly out of nowhere, is much like how milk curds appear, according to a new analysis. The study, published last week in the journal Physical Review Letters, could help law enforcement and intelligence agencies identify extremist groups -- and possibly even fake social media accounts aimed at stoking division and discord, said Neil Johnson, a physicist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and one of the authors on the new paper.

To make and test the model, Johnson and his colleagues used data from VKontakte, collected during the flurry of activity between 2014 and 2015, before the social network shut down the extremist groups. For the last few years, the team has been modeling the behavior and evolution of these groups. Now, in the new study, they have homed in on how such extremist groups begin.

Johnson realized that the sudden appearance of these groups is similar to something he learned in graduate school: the physics of gels. Milk curds are a type of gel, and when they form, the microscopic milk particles glom onto one another until, at a certain point, they become macroscopic chunks. "You wouldn't visibly see any curds form," Johnson said. "Then there's a moment that it just appears out of nowhere." The researchers took the equations that describe this phenomenon and applied it to groups in social networks.

But while milk curdling is due to the clumping of proteins that are similar, people are different. So to mimic this diversity, the researchers assigned a number between 0 and 1 that represents an individual's "character." It's an oversimplification, Johnson said, but the point is to hint at the variety of a social network in real life.

The approximation was good enough, as the gel model closely matched the data from VKontakte. The extremist groups that exploded in number and size between 2014 and 2015 accumulated followers similar to how particles clump together to form gels. The researchers could even predict when groups would form. The more similar individuals are in terms of their "character" rating, the faster they coalesced into groups.

This rapid growth is unique to extremist groups, Johnson said. "The local karate club does not do that." By finding the online groups that behave like gels, you could then, in principle, identify groups that have a higher likelihood of breeding extremist activity. With tens of thousands of online groups on VKontakte, finding the few hundred extremist ones -- whose members often communicate in code and hide their motives -- is a challenge. By filtering out those 1 percent that may harbor individuals with intent to harm, the model could narrow down which groups need to be investigated, Johnson said.

It's always a struggle to predict which individual might inflict harm, said Paul Gill, a crime scientist at the University College London, who wasn't involved in the work. "We've got finite resources, and far too much noise" in social networks, he said. "How models can help is guide our finite resources toward as small a group number as possible."

The model's usefulness will depend on whether it also mimics the behavior of other groups on other social networks, said Gill, who studies how those with extreme views turn violent. "The next big challenge now is to collect data on ISIS supporters on multiple social media platforms and look at other extremist groups to see whether there really is something here that's generalizable."

The researchers are now turning their model to other groups like white supremacists, Johnson said. They're also analyzing whether groups that are passionate -- but whose views may not be necessarily violent or extremist -- also exhibit gel-like growth. If so, the model may help suss out fake social media accounts meant to fan the flames of political passions.

For example, just last week, Facebook announced it identified 32 fake accounts trying to disrupt and influence U.S. elections. The company couldn't confirm who was responsible, but the methods of the faux profiles were similar to those of the Russia-linked Internet Research Agency.

The accounts created pages and events that contained content appearing to appeal to left-wing politics and exploit today's heated political climate. If such pages and events indeed grow like the pro-ISIS groups, Johnson said, then the model could also help Facebook and government agencies identify the fake accounts. While these political groups may not be as extreme or violent as pro-ISIS groups, they may grow and behave similarly, attracting followers spurred on by a sense of urgency and the feeling that they're under attack, Johnson said.

The new model underlines the importance of looking at collective behaviors rather than individuals, he said. In fact, the conventional strategy of sifting through social networks for individual terrorists may be misguided.

Gill agrees that studying group behaviors is important, especially since group settings can embolden people. "Rarely does radicalism or extremism happen by itself," he said. "To understand radicalization and extremism, we need to keep looking at it through a group lens."