Fossil Tracks Reveal Lightning Speed of Dinosaurs

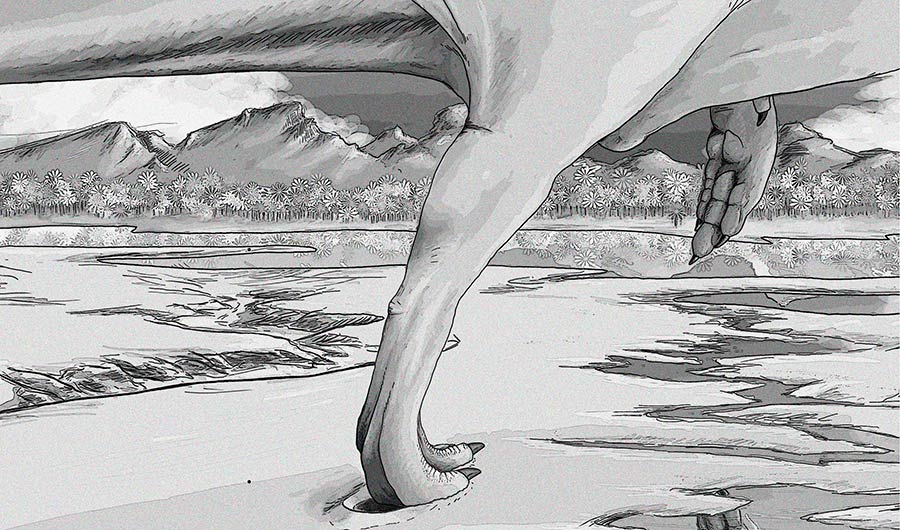

Artist's rendition of a theropod dinosaur running through sediments.

Pablo Navarro-Lorbés

(Inside Science) -- All that’s left is footprints in fossilized mud, but the tracks reveal how some theropods of the Lower Cretaceous may have ran as fast as Usain Bolt at his best sprint.

“Our speeds are the third faster dinosaur tracks registered to date,” said Pablo Navarro-Lorbés, a doctoral student in paleontology at the University of La Rioja in Spain who studied the prints.

Starting in the 1980s, thousands of dinosaur tracks dating between 125 million and 120 million years old were discovered in the area around La Rioja. Navarro-Lorbés and his colleagues wanted to see how fast some of the three-toed theropods may have been traveling, homing in on the tracks of two individuals with long strides. Theropods include a diverse group of dinosaurs that moved on two legs, including tyrannosaurs, velociraptors, and many others. One of the La Rioja tracks includes five footprints over a span of about 43 feet (13 meters), though one footprint in the middle was presumably lost to the fossil record. The other includes seven footprints over about 56 feet (17 meters), with the last print indicating the dino veered sharply leftwards.

In a study published today in the journal Nature, the researchers calculated the dinosaurs’ hip height based on the 30-centimeter (about 12 inch) length of the footprints. They then compared the hip height to the stride with an updated formula for speed calculation used by paleontologists. “The distances between footprints are huge,” Navarro-Lorbés said.

They found that one individual was moving between 14.5 and 23.1 mph while the faster one traveled between 19.7 and 27.7 mph. The top estimated speed is faster even than the roughly 25 mph estimated speed of velociraptors, though since a similar trackway study hasn’t been conducted on the latter it’s hard to make a direct comparison.

“I’m amazed at what they do -- high level science,” said David Poole, a professor of kinesiology, anatomy and physiology at Kansas State University who was not involved in the research.

Poole has studied the speed of terrestrial animals such as horses and dogs. While the top speeds of the theropod clocks in near sprinter Usain Bolt’s top speed of 27.8 mph, the dinosaurs don’t come close to animals like horses, which can reach about 55 mph, or even greyhounds, which can reach about 45 mph. Cheetahs can exceed 60 mph, according to Guinness World Records. The ostrich, which may be the closest living analogue of theropod dinosaurs, can reach about 40 mph, Poole said.

Stride isn’t everything, Poole noted. Olympic gold medal-sprinter Michael Johnson had a relatively short stride at 7.2 feet (2.2 meters), and was only slightly slower than Bolt, whose stride averaged 8.9 feet (2.7 meters).

But Navarro-Lorbés said that these considerations were built into the formula, which was tested using the strides of humans and other animals to ensure accuracy.

The researchers believe the two tracks are from the same species, but it’s unclear from the footprints alone which one it was. It’s possible they were Spinosaurids or Carcharodontosaurids, two theropods commonly found in Spain dating to this period.

It’s also difficult to say why they needed to run so fast.

“Part of this makes me wonder what it’s chasing, or what’s chasing it,” Poole said.

The dinosaurs’ size doesn’t necessarily help solve the conundrum. Based on the footprint, the dino would have stood about 2 meters tall and would have been about 4-5 meters long from head to tail, Navarro-Lorbés said.

“For this range of sizes, they were more or less big predators, but not the biggest. They needed to be fast to chase prey and to run away from bigger animals than them.”

Either way, Navarro-Lorbés said it’s likely that this speed represented short bursts, partly because “fast tracks around the world are very scarce.” Since these tracks were made in relatively deep mud, it’s also possible that these theropods might have been even faster on terrain that offered less resistance, he said.