Laboratory In A Needle Promises Rapid Diagnosis

Image credits: Courtesy of Houston Methodist Research Institute and Nanyang Technological University

(Inside Science) – Researchers in the U.S. and Singapore have designed a miniature chemistry laboratory inside a needle that could yield almost instantaneous results from routine laboratory tests, potentially accelerating the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions.

The prototype device, created by miniaturizing existing "lab on a chip" technology, has shown its capability in studies of mice with liver toxicity, a common side effect of cancer chemotherapy in humans.

"It really integrates the whole laboratory process in one testing without any human in between," said Stephen Wong of Houston Methodist Research Institute and Weill Cornell Medical Center, who created the idea for the new technology.

Diagnosis of medical conditions depends on the results of blood tests to identify toxicity and potential reactions to drugs. Obtaining the results of the tests can typically take a week. However, Wong said, "Using our approach, it takes less than an hour."

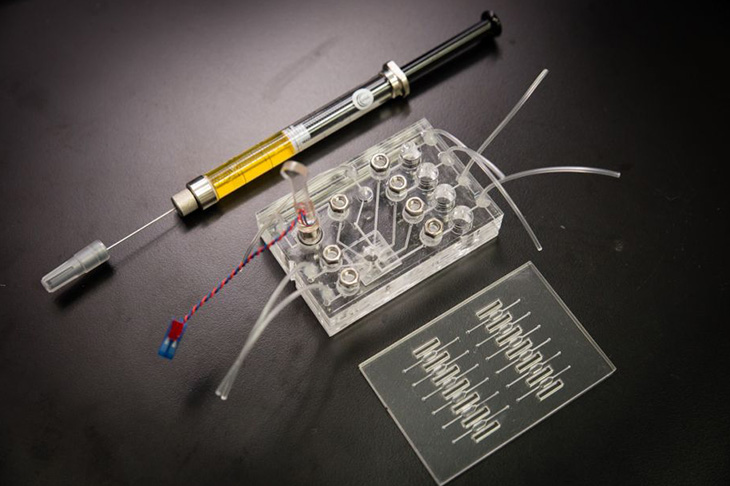

The patented design combines individual components from a chemistry laboratory into a single small package attached to a conventional 32-gauge needle, a size used for several simple injections.

"This is a change in paradigm – a really disruptive technology," Wong said. "You are no [longer] tied down to the lab" to carry out diagnostic procedures. "You can have a wireless device attached to your cell phone."

Medical specialists could use the technology in healthcare offices, patients' homes, or even remote locations to carry out diagnoses normally performed in hospitals.

"It's a point-of-care mobile device," Wong said. "But it can also be a device that you can use during the surgery to get instant results." That would permit doctors and patients to discuss treatment options as early as possible.

"I found it very exciting," said Shari Rubin, an internist at Houston Methodist Hospital. She was not involved in the research.

"Many of our patients travel really far to come to the medical center for blood work," Rubin added. "If you can have them do things at home, that would be incredibly helpful. Anything that can keep patients away from the hospital is wonderful."

She noted, however, that developers of the technology would need to persuade patients to use it at home and to convince insurers to cover it.

The technology stems from the "lab on a chip" approach.

"This is basically a device that includes one of several functions on a single chip, measuring square millimeters to a few square centimeters," Wong said. The approach combines microfluidics, a technology that deals with miniscule volumes of liquids, and semiconductors, the gizmos at the heart of all modern computers and communications methods.

The lab on a needle is designed to carry out several steps in testing a patient's tissue sample for any particular medical condition. It extracts the sample; prepares it; amplifies the material in it called messenger ribonucleic acid, or mRNA, a carrier of genetic material; and runs a process called the polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, to detect the existence and concentration of the gene or genes related to the sought-after disease.

The prototype needle uses two chips. The first carries out the initial three tasks while the second contains the chemicals that perform the PCR process.

"The prototype puts the two chips together and obtains a readout," Wong said. "We've proved that the two can be put together in one package."

To test the prototype needle, the team hit on liver toxicity, which has the advantage of needing only two genetic markers to identify it.

Wong's group induced liver toxicity in mice and used the needle to identify the markers for it, and the lack of the markers in untreated mice. They reported the results in the online publication Lab on a Chip.

The researchers emphasize that their lab in a needle is still in the development stage.

Wong's team, along with collaborators in Singapore's Nanyang Technological University and the Singapore Institute for Manufacturing Technology (SIMTech), are now engineering a practical version of the technology.

The teams also plan to develop the necessary procedures for testing the needle in humans. Those tests will seek the same genetic markers as the studies involving mice. But they will have to comply with much tighter government regulation.

The research team also aims to apply the technique to various medical conditions.

"We are planning to test other tissues or body fluids based on respective testing protocols for other human disease detection and diagnosis beyond liver toxicity," said Zhiping Wang, director of research programs at SIMTech, in an e-mail message.

"The concept is working; the rest will be engineering," Wong said.

If it passes the trials, the device could yield significant improvements in clinical practice.

"It's less risky, faster, and cheaper than current methods," Wong said. It also puts the lab on a chip concept at the service of medical personnel in addition to life scientists in the laboratory.

"In the long run if it's successful it can deal with everything," Wong said. "We try to bring the hospital to the patient, not the patient to the hospital."