Mouse Sperm Kept in Space Station Produced Healthy Young on Earth

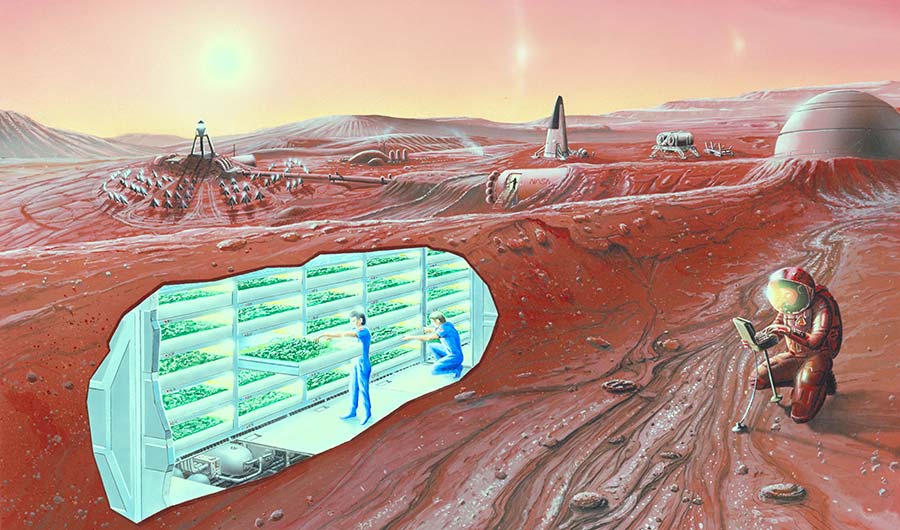

Artist's concept of possible colonies on future Mars missions.

(Inside Science) -- To the best of anyone’s knowledge, no one has had sex in space.

Only one married couple have been on the same mission, the Americans Mark Lee and Jan Davis, and according to NASA, nothing happened. There being no privacy in the space shuttle or the International Space Station, that is likely true.

But with NASA exploring ideas such as two-year voyages to Mars and eventual colonies on Mars and the moon, the question of reproductive safety is important, especially if humans wish to one day travel to the edges of the solar system and even beyond. Can space voyagers conceive healthy human babies?

Two factors are involved -- microgravity and radiation -- that could affect sperm, eggs and fertilization. Microgravity tests on birds, sea urchins, amphibians and fish have proven inconclusive. If there was any damage, researchers were unable to detect it.

But radiation from the sun and cosmic rays is 100 times stronger in space than on Earth, which is protected by a layer of ozone and the Van Allen radiation belts. In tests on Earth, radiation similar to what astronauts would encounter has been shown to cause mutations in DNA and embryos, as well as an increase in tumors. Unprotected astronauts might be more susceptible to cancers.

But what would happen if scientists tried to use artificial insemination with preserved sperm and eggs to help space travelers or colonists get pregnant?

Earlier experiments in labs hinted that mammalian reproduction is adversely affected by space conditions. But for various reasons, the results mostly showed how difficult it was to produce verifiable results.

A team of Japanese scientists decided to see how well mouse sperm kept if it was freeze-dried and sent aboard the International Space Station for an extended period.

They sent the sperm in glass vials to the station Aug. 4, 2013, where it was kept at -56 degrees Farenheit, and brought it back to the ground 288 days later, on May 19, 2014. They used a similar setup in a laboratory on Earth as a control. Both sets of sperm samples were exposed to the same temperature changes, but only those that traveled to the space station experienced microgravity and the radiation present in space.

The researchers then used both the space sperm and the lab sperm for artificial insemination into female mice, and compared the individual cells, embryos and offspring.

They found some changes to the DNA in the space samples, but not enough to affect the ability of the sperm to fertilize eggs or produce baby mice. The survival rate and the fertility of the babies was the same.

In a paper published online today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers suggested the DNA was able to repair itself.

What works on mice, scientists know, does not necessarily work for humans. The question is: What good does it do to know how this experiment worked out? It's unclear when it would be necessary or desirable for humans to reproduce in a space station or on another body in the solar system. Whenever that time comes, having babies might require the use of assistive reproductive technology.

"Already a lot of babies were born from preserved sperm. I think this will continue even for humans [who] live in space," said Sayaka Wakayama of the University ofYamanashi, in Japan, one of the researchers who conducted the study.

But human reproduction in space may not be the only concern. Future space colonists might want to have terrestrial fauna with them, either for work, for food, as pets, or just for aesthetics. Carrying and keeping horses, cows and chickens into space would be too expensive and difficult. Bringing the ability to artificially inseminate eggs -- to build your own horse, for example -- would be the solution. Such projects would have to make use of artificial wombs.

Freeze-dried sperm can probably be kept at room temperature for two years, and it would last indefinitely in a freezer, the researchers said. Since the strength of a species depends on diversity, reproduction could be managed for maximum efficiency.

But what about humans?

"Astronauts are already aware of the radiation risks and are currently counseled about cryopreservation of sperm and eggs as a measure to minimize risks due to radiation exposure," said Joseph Tash, professor of molecular and integrative physiology and urology at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. Tash is also past president of the American Society for Gravitational and Space Research.

"As for the astronauts and future long term space habitants, ovaries and testes are the most sensitive organs to both acute and chronic radiation exposure," he said.

Tash also points out a possible flaw in the Japanese research, demonstrating how hard it is to do these investigations.

The International Space Station orbits beneath the Van Allen belt, so the radiation the mouse sperm endured was not even close to what would happen in deep space.

"Long term," Tash said, "the feasibility of mammalian reproduction in space beyond the Van Allen belt will depend on the creation of radiation-hardened facilities that can protect gametes from [cosmic] radiation exposure.

"The pregnant mother would also need to be protected by such a facility. So it presents very real habitat, medical, social and psychological questions that need to be addressed as well."