The Rural Challenge of HIV

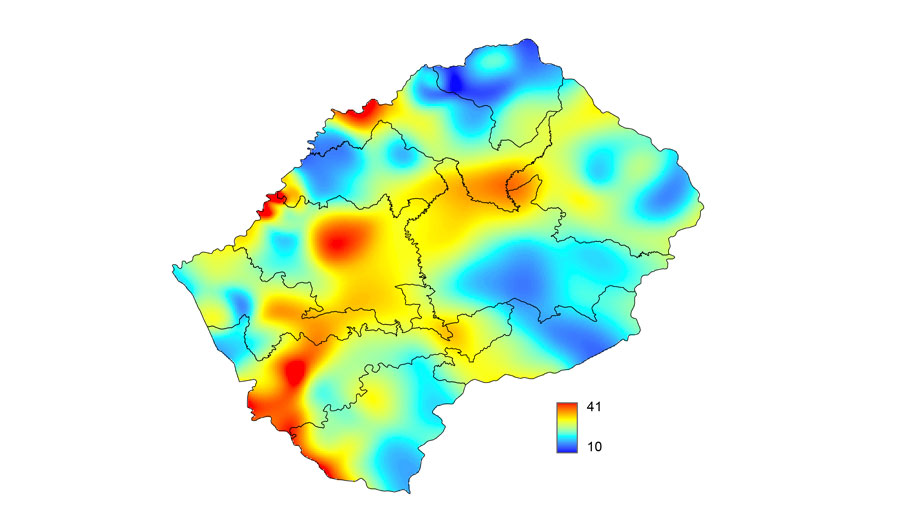

HIV epidemic surface prevalence map for Lesotho. The color scale indicates the percentage of the population aged 15-49 years who is infected with HIV.

Image created by Justin T. Okano

(Inside Science) -- A new map developed by researchers at UCLA in California calls into question whether a U.N. strategy for eliminating AIDS will succeed in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of people living with HIV reside.

The map models where people infected with HIV live among the mountains and high plains of Lesotho, a small, landlocked nation in South Africa about the size of Maryland. And in a new study, the UCLA researchers use the data from this model as a roadmap to design an optimal strategy for eliminating HIV.

Their elimination strategy is based on a concept known as "treatment as prevention," which is built on evidence that treating people with antiretroviral drugs makes them less likely to transmit the virus to others. Many experts now believe the HIV/AIDS pandemic could be ended within a generation if treatment as prevention and other existing means of stopping the virus were fully implemented.

This conviction is enshrined in the "90-90-90 goal" of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), which seeks to diagnose 90 percent of people living with HIV, treat 90 percent of those diagnosed and successfully control the virus in 90 percent of those treated, all by 2020.

However, the new research calls into question whether the 90-90-90 strategy as envisioned by the U.N. will succeed. "It won't in the very rural countries," said Sally Blower, a professor at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine, who led the study.

Everybody in the world who is infected with HIV deserves treatment, Blower said, but for treatment as prevention to work, it must account for the geographic dispersion of people infected with HIV.

The UNAIDS strategy calls for dividing treatment resources among districts based on the number of infected people therein. But in Lesotho, this would require spreading resources thinly over sparsely populated rural areas and would hinder, and possibly even prevent, HIV elimination, according to the paper, which was published in March in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

A better approach may be to optimize resources by dividing them on the basis of geographic dispersion, the paper suggested, concentrating them in districts with urban areas and rural settlements that are larger and clustered more closely together as opposed to rural areas where settlements are small and far apart.

Drugs Transformed AIDS -- Could They Someday End it?

Antiretroviral HIV/AIDS drugs are one of the greatest medical success stories in the nearly four-decade fight against the disease. Tens of millions of people around the world are now taking these drugs, and millions of lives have already been saved. The drugs work so well that they have transformed what it means to live with AIDS and have shaped the public health response to the disease worldwide -- both for treating people who are already infected and for preventing new infections.

The idea of treatment as prevention is that as more and more people take antiretroviral drug cocktails, fewer and fewer new cases will occur.

Some early evidence that treatment as prevention may work came from studies in Vancouver, British Columbia and San Francisco, which suggested widespread treatment reduced the spread of HIV in those communities.

Solid evidence directly demonstrating the "biological plausibility" of treatment as prevention came from a large clinical trial called HPTN 052, the final results of which appeared just last year -- though the initial results were unmasked in 2011 because they were considered promising enough to release years ahead of schedule.

HPTN 052 showed that when people took antiretroviral drugs and when the drugs worked -- meaning they suppressed the virus -- that in turn dramatically reduced the spread of HIV between "discordant" heterosexual partners (where one partner is infected and the other is not).

"We proved that there was virtual elimination of transmission when suppression was achieved," said Myron Cohen, a doctor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who led the HPTN 052 clinical trial.

And another study, led by UCLA's Blower, showed that treatment as prevention worked in the country of Denmark, where the number of new HIV infections has been decreasing. But that success, Blower said, came under almost ideal conditions.

Efforts to combat the disease were well established in Denmark, going back decades. The nation's system of socialized medicine guarantees universal free access to high-quality treatment, and antiretroviral therapies have been available there since they first arrived on the scene in the 1990s.

"When you have all that, you really can have treatment as prevention working," she said.

From Denmark to Lesotho

Blower's new study is the first to look at the problem of implementing treatment as prevention in Lesotho -- a country where almost a quarter of the population is infected with the virus, ranking it high among the worst HIV epidemics in the world.

To model the geographic dispersion of people living with HIV in Lesotho, Blower and her colleagues incorporated satellite data, census data and HIV testing data and applied mathematical modeling to all of it. They found that rather than residing mostly in large urban centers, people infected with HIV were geographically dispersed throughout the countryside. Only one-fifth live in urban areas, and almost all rural communities have at least one HIV-infected individual, according to the study's model.

This dispersion confounds one of the basic precepts of the UNAIDS strategy, which holds that as more people are treated, the treatment will become cheaper. "Our study turns that on its head," Blower said, because it becomes harder and more expensive to scale up treatment when that community is rural and dispersed.

Other experts acknowledge that the hurdles identified in the new study need to be considered as 90-90-90 continues to roll out.

"Ultimately there isn't a one-size-fits-all answer for this. Each epidemic is different, and each country has its challenges," said Carl Dieffenbach, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland.

NIAID is a component of the National Institutes of Health and a major U.S. funding agency for AIDS research. NIAID funds Blower's work, but Dieffenbach was not directly involved in the research and had not read the manuscript until after being contacted by Inside Science.

"Everybody wants a magic bullet," he said, "but there isn't going to be one."