Safer Bricklaying with Artificial Intelligence

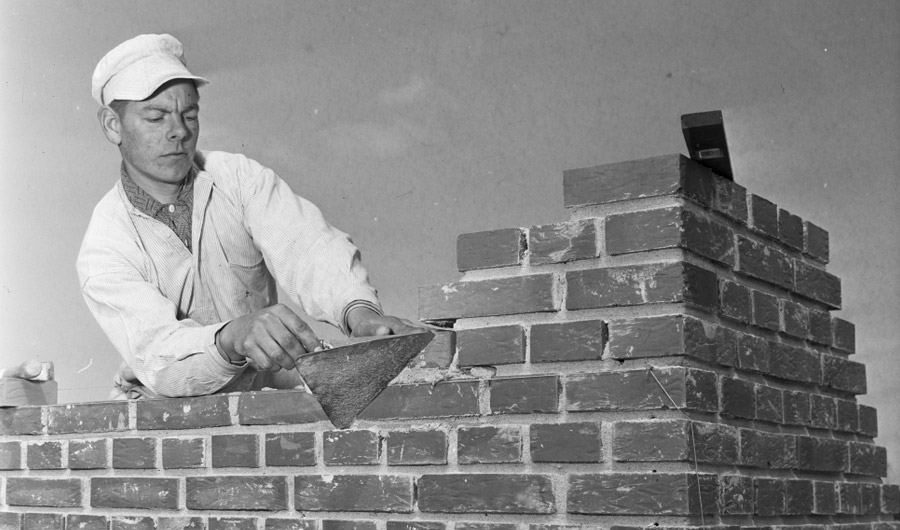

IMage credits: The Royal Library, Denmark

(Inside Science) -- Bricklaying is repetitive and strenuous. It takes a toll on your body, potentially spraining, tearing and straining ligaments and muscles. But new technology is now helping to identify the safer techniques master masons use, gaining insights that can improve training.

Musculoskeletal injuries like sprains and strains account for a third of all illnesses and injuries among general construction work, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. They cause workers to miss time and, in some cases, to leave the industry all together -- depleting an aging and already shrinking workforce.

Improved safety measures over the last couple decades have led to a steep drop in injuries due to accidents. But reducing injuries caused by cumulative stress on joints and muscles is much trickier. "It's something that people weren't aware of," said Carl Haas, a civil engineer at the University of Waterloo in Canada. As awareness has grown, he said, new tools are now available to identify the source of these injuries and how they can be prevented.

These tools include motion-capture suits, which are often used in the movie industry and in sports research. They've become relatively inexpensive. Recently, Haas and a team of engineers used the suits to learn how masons can work more safely, tracking the workers' body postures. After analyzing the data with artificial intelligence software, the researchers discovered that experienced masons have developed efficient techniques that place a lighter load on their joints, lowering the risk of injury.

"If somebody has been doing it for 25 years, they've found a way to do it safely," said Eihab Abdel-Rahman, a systems design engineer at the University of Waterloo, and an author of the study, published in the journal Automation in Construction.

For the study, the researchers observed 21 masons -- including longtime professionals, complete novices and those with one or three years of experience -- at an apprentice program in Ontario. The experts averaged five times the experience of the others. Artificial-intelligence software identified subtle-but-notable differences among the groups.

When lifting bricks, the researchers found, expert masons don't bend their backs as much as less-experienced bricklayers. Experts also carry bricks closer to their bodies. Both techniques result in lighter loads on the individuals' lower backs and shoulder joints.

The researchers are already passing on these tips to masons-in-training. They have partnered with the Canadian Concrete Masonry Producers Association and the Canada Masonry Design Centre, who in turn work with apprenticeship programs across Canada, to develop a list of do's and don'ts. "There is a way to save a lot of careers," Abdel-Rahman said.

The results also help explain a curious pattern. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, construction injuries tend to rise in the first few years of a worker's career. But after the fifth year, the injury rate drops.

The researchers saw a similar trend in a previous study on masonry. Using video cameras to measure bricklaying postures, they calculated the load placed on joints. They found that experts feel lighter loads on their joints -- but so did novices. Those with an experience level between expert and novice -- masons who had been working a couple years -- felt heavier loads. "That is not expected because you would expect that as they gained experience, they would do it in way that protects themselves," Abdel-Rahman said.

One explanation, which the new study supports, is that novices are less confident, so they're more careful and work slower. "But what we're finding is that the second or third-year apprentices, in order to keep up with master masons in terms of productivity, begin to move and work in physically unhealthy ways," Haas said. These second and third-year apprentices gain confidence and work faster, but their technique remains poor. Only after yet more years of experience do they figure out the subtler and safer tricks of a master. If they don't, they might hurt themselves and be forced to change careers.

The new approach, which can also apply to other construction work, has enabled researchers to quantify and visualize safe and unsafe positions for the first time, said SangHyun Lee, a civil engineer at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who collaborated on the older study but not the new one. "This allows us to understand how and why an experienced mason is more efficient and more safe," he said.

Most recently, the researchers performed a similar study on rebar tying, which involves tying bars of reinforcement steel together for laying concrete. According to the initial data, Abdel-Rahman said, one particular technique results in twice as much force on the lower back as another.

The technology is there to keep workers healthy, which is good both for them and the company, he said. "It's doable, and it's not just for bricklaying."