Two Liver-Destroying Viruses, Two Nobel Prizes

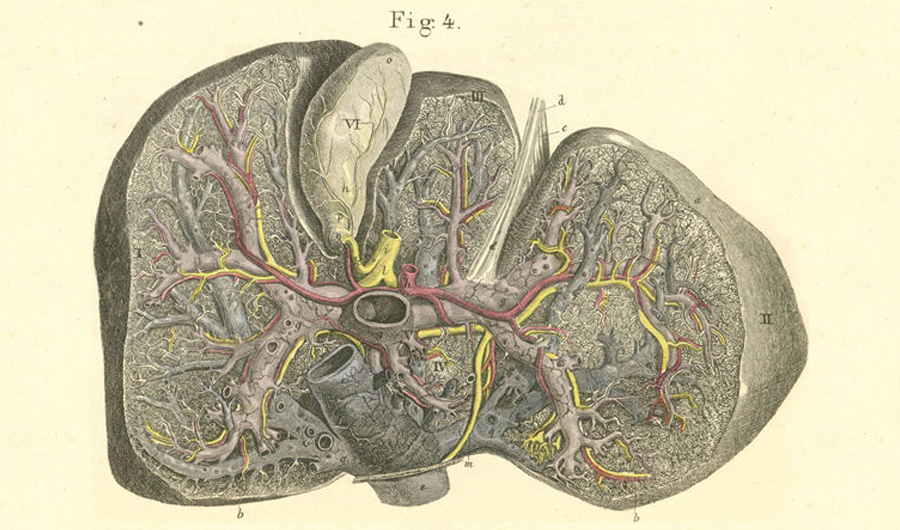

Qasim Zafar via Flickr. From "Atlas of Human Anatomy" by Carl Ernest Bock.

Public Domain Mark 1.0

(Inside Science) -- If you need a blood transfusion today, you can receive one without the fear of catching a life-threatening liver disease. That's largely thanks to research that has now been honored with two Nobel Prizes. On Monday, Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles M. Rice were named the winners of the 2020 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for their discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C. But 44 years ago, Baruch S. Blumberg won his own Nobel Prize for discovering the virus that causes hepatitis B.

Hepatitis is the term used to describe inflammation of the liver, and it can lead to liver failure and cancer. Several types of viruses can cause hepatitis, but the bulk of cases transmitted by blood are hepatitis B or C. In one study that reanalyzed old blood samples from people who underwent open-heart surgery in the 1960s, 44 out of 66 people apparently became infected during the procedure; 13 contracted the hepatitis B virus only, 24 contracted the hepatitis C virus only and seven caught both viruses. About two-thirds of the infected people developed the disease hepatitis.

Most healthy adults can clear hepatitis B from their bodies within a few weeks, and some people will clear hepatitis C infections as well. But in many cases, the infections turn chronic, often lurking for years before emerging to cause serious damage. The ability of the viruses to hide without causing symptoms made them hard for researchers to identify. The discovery of hepatitis C involved hunting down the virus's genetic material, an approach that wasn't available to Blumberg in the 1960s.

Blumberg was a doctor and geneticist who collected blood from people from all over the world. He and his colleagues -- including Alter, one of this year's Nobel winners -- found in laboratory tests that blood samples from an Aboriginal Australian person reacted with blood samples from people with hemophilia who had received multiple transfusions. The reason, it turned out, was that the first person's blood contained hepatitis B virus particles, and the blood from people with hemophilia contained antibodies that attacked that virus. When drops of blood from both people diffused toward each other through a slab of gel, a telltale sliver of protein crystals formed at the spot where the viral particles and the antibodies met.

The people with hemophilia most likely had antibodies because they had recovered from hepatitis B in the past, said Timothy Block, president and CEO of the Hepatitis B Foundation and its Baruch S. Blumberg Institute, a nonprofit medical research organization. The Aboriginal Australian person must have had a chronic infection that was not prompting production of antibodies.

While the hepatitis B and C viruses were discovered in different ways, both advances pioneered the use of influential research techniques, said Block. And while the viruses still pose major health challenges worldwide, he added, their discovery has already saved millions of lives.

"What a wonderful thing to be able to celebrate and recognize," said Block. "It's really what the Nobel Prize is all about."