Children Learn Cursive by Teaching Robots

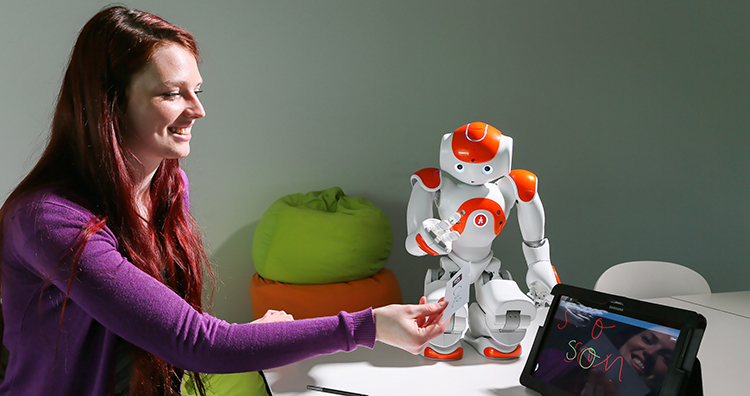

Image credits: Courtesy of EPFL

(Inside Science) – A team of Swiss and Portuguese scientists has developed a "learning by teaching" program intended to help children improve their handwriting skills by teaching robots to write letters of the alphabet.

In preliminary studies of the prototype system, elementary school children starting to learn cursive script successfully engaged with a small humanoid robot and improved the robot's handwriting to a level that satisfied the children.

The next step will quantify the impact of those interactions on the children's handwriting.

Séverin Lemaignan, a member of Computer-Human Interaction in Learning and Instruction Laboratory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (abbreviated in French as EPFL) outlined the group's philosophy at the Conference on Human-Robot Interaction in Portland, Oregon this month.

"Get a child-proof robot to write badly," he explained. "Then make it able to learn with the help of children."

Essentially, Lemaignan added, "the goal is to provide a tool for teachers that is given a new role in the classroom – that of a student who knows even less than the slowest student in the class."

The bottom line, said James Hendler, director of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute's Rensselaer Institute for Data Exploration and Applications in Troy, New York, and coauthor of the book Robots for Kids: Exploring New Technologies for Learning, "is this was a really clever project that took several emerging trends and put them together in a very cool way."

The project brings together robot technology and child psychology.

"One of the breakthrough technologies we're seeing in robotics is an increasing ability for robots to be trained, rather than programmed, by humans thanks to new sensor- and machine-learning technology," Hendler pointed out. "The EPFL team has come up with the extremely clever idea of combining this with the motivation children find in working with robots to make it so that both the robots and the humans learn together, each strengthening the other's skills."

The research program, called the CoWriter Project and carried out in collaboration with the school of engineering at the University of Lisbon in Portugal, started with the choice of robots.

The team selected the off-the-shelf Nao robot made by Aldebaran Robotics. This 2-foot tall robot "is well suited for this kind of experiment because it is robust and safe enough to be operated with children in natural environments," Lemaignan said. "It also looks human-like yet not impressive, which fits well the role of 'the student who faces handwriting difficulties' that the robot plays."

Software engineers then programmed the robots to act in precisely that way.

"That definitely constitutes one of the main scientific contributions, and relies on pretty advanced mathematics to analyze existing samples of handwritten letters to first extract the natural variations and then exaggerate them to build new, deformed letters," explained Lemaignan, who carried out the research with EPFL colleagues Deanna Hood and Pierre Dillenbourg.

In their initial studies, the team paired robots with French-speaking children between 6 and 8 years old who had begun to learn cursive writing.

In action, each child uses small magnetic letters to show his or her robot a word. The robot writes the word on a tablet and asks for feedback. The child takes the tablet, corrects the entire word or individual letters with a stylus, and gives the tablet back to the robot, which has another try at writing the word.

"We repeat this turn taking until the child is satisfied, and decides to show a different word," Lemaignan said.

To validate its technology, the team carried out studies in two schools, involving about 50 students, as well as a third experiment with a 6-year-old child who had been having difficulties with writing.

The students interacted with the robots as the experimenters had hoped. "When asked, children would say that the interaction was playful, in that they saw the robots as playmates," Lemaignan recalled. "They also took it seriously; they had to help the robot to improve, and were quite engaged in this role. In that sense, they also perceived the robot as a student."

But did instructing the robots improve the children's writing skills?

"The impact of the robot on the children's handwriting is yet to be assessed in a formal way," Lemaignan said. "We are currently preparing a new set of experiments to take place before the summer, focusing on this last, key point."

The next steps in the program will depend on the results of those experiments.

"We first need to be sure that the robot has indeed the positive effect on handwriting that we expect," Lemaignan said. "We also need to improve its autonomy; even if the robot is autonomous from a strict technical perspective, the interaction is currently quite basic, and the presence of an experimenter/teacher is required to prompt the child to give feedback, to decide when to switch to a different word, and other tasks."

The team is also planning long-term studies. These have the goal, Lemaignan said, "of getting a better picture of what kind of long-lasting interaction shapes up between the children and the robot."