How Do Giraffes Drink Water?

Giraffes, the tallest animals on earth, seem to pump water up their long necks, a new study says.

(Inside Science) -- The giraffe's neck — useful for reaching the loftiest acacia leaves or for slugging would-be rivals — has its drawbacks. When the creature stoops to take a drink, for example, it must spread its front legs and lower its head to the water's surface. How a giraffe, the tallest animal on earth, then propels that water up its long neck to reach its stomach has been a mystery. Now, new research suggests the secret may lie with a simple device known as a plunger pump.

The spark that kindled this insight struck Philippe Binder last year in Namibia's Etosha National Park. He was sitting in a tour bus, watching a giraffe drink from a nearby watering hole.

"I thought, 'Wow, this is weird. Getting water up that long neck can't be easy,'" he said.

Binder is a physicist at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, where he studies nonlinear dynamics and chaos theory and seldom encounters giraffes. But while on sabbatical at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, Binder couldn't get the image of the thirsty giraffe out of his head.

"Physicists often have a childlike curiosity to know why things do what they do," he said. "I just wanted to understand how giraffes drink. It was sheer, pure fun."

He enlisted the help of Dale Taylor, a physicist at the University of Cape Town, and the two set about accumulating giraffe minutiae — neck length, esophagus capacity, length of typical drinking episodes — and searching for possible mechanisms behind the behavior.

More on giraffes from Inside Science

At first, the researchers thought that the animal might be using its neck like a giant, 8-foot-long drinking straw — lowering the air pressure in its esophagus and stomach and allowing atmospheric pressure to push the liquid up its esophagus. But they scrapped that idea after calculating that giraffes are likely unable to generate the pressure difference needed to lift the water from their lips to their shoulders.

Then two clues pointed them toward plunger pumps: a veterinary and medical textbook from 1890 that said ruminants like cows and sheep use their tongue like a plunger to pump water into their esophagus and a YouTube video with a close-up of a giraffe at the Phoenix Zoo in Arizona drinking in a suspiciously pump-like way.

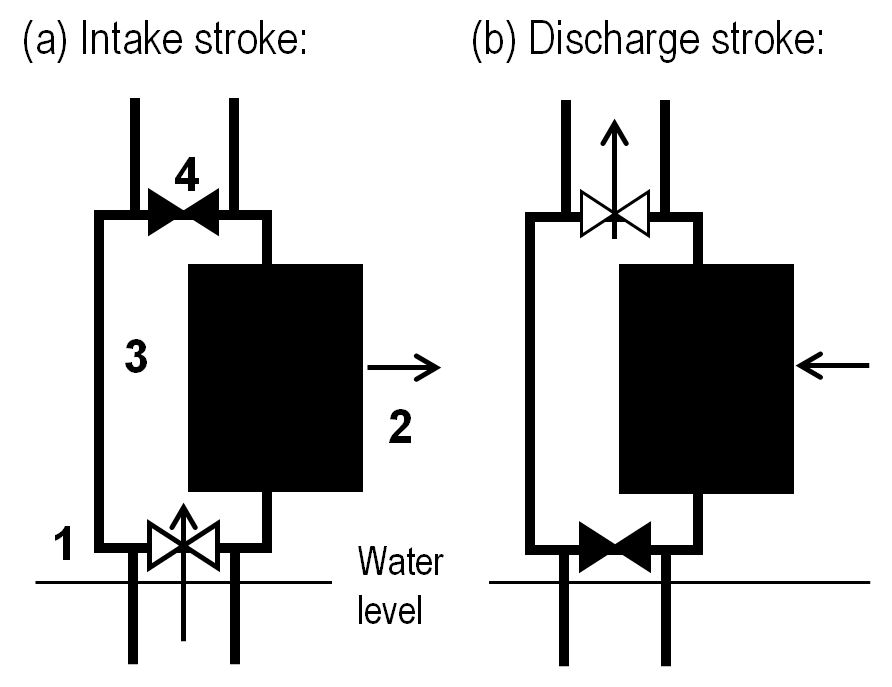

Typically, a plunger pump uses one stroke to draw water or other fluids into a cavity through one valve and then another stroke to push the liquid out again through a second valve. Variations of the pump are common in wastewater treatment and the oil and gas industry.

But where do giraffes store their plunger pumps?

In the model proposed by the researchers, the giraffe's lips form one valve of the "pump" while the animal's epiglottis, located at the back of the mouth, is the other. To start, the giraffe sinks its puckered lips into the water and then pulls back its jaw, allowing water to rush into the mouth while keeping the epiglottis "valve" closed. Next, the giraffe clenches its lips, relaxes the epiglottis, and pumps its jaw so that the captured water is pushed into the esophagus.

The cycle repeats, moving more and more water into the esophagus. At some point, the giraffe lifts its neck, and the water sluices into its stomach, thanks to gravity and the wave-like muscular contractions known as peristalsis.

The researchers estimate that the giraffe pumps water in at a speed of about 6.7 mph — fast enough to overcome the pressure from the water that's already stored in the esophagus and preventing it from rushing back out.

Based on the dimensions of a giraffe esophagus, the researchers estimated that a full one can hold about 1.3 gallons. Additional calculations revealed that each pump probably sends about 10 ounces of water into the throat and that a long drinking episode of about 25 seconds could involve up to 17 pumping cycles. Thus, a parched giraffe would nearly fill its esophagus to the brim, according to Binder and Taylor's research, published in December in the journal The Physics Teacher.

"It's a really good observation," said Sunghwan Jung, a biophysicist at Virginia Tech, who wasn't involved in the research. "But to know for sure whether giraffes drink this way, they'll need to use X-rays to see inside the mouth."

In the past, Jung and his colleagues have employed high-speed photography and engineered models to reveal how other animals such as cats and dogs drink. Those animals use a different strategy than giraffes or other herbivores like cows and horses, he said. Rather than putting their lips on the water surface and opening their mouth, cats and dogs "push their tongue in and out and create a water column in the air, which they bite down on."

X-rays would be illuminating and perhaps reveal what role, if any, the giraffe's tongue plays in the process, said Binder. But he's skeptical many people would be willing or able to secure the leggy animal's cooperation. "Besides, what X-ray machine would be big enough?"

Instead, he's considering looking into using such a technique on smaller targets like goats to see if they drink in related ways. In the meantime, said Binder, "I know I'll never look at a giraffe the same."

"I've always wondered how giraffes get water all the way up that big, long pipe," said David O'Connor, a conservation ecologist at the San Diego Zoo who has studied the stately creatures in the wild. But, he said, it's just one of the many mysteries that envelop the animals. "We don't even know for certain why the long neck evolved. It certainly wasn't for drinking."