Using Social Networks to Analyze the Classics

(Inside Science) -- It is possible that a man named Achilles really did once sail across a wine-dark sea to his death, and a Nordic warrior named Beowulf really lived and fought, although it is highly unlikely he ever slew a monster. A computer says so.

Using the same mathematics that makes Facebook work, researchers at Coventry University of England analyzed three legends, Homer's "Iliad" (written around 800 B.C.), "Beowulf" (written around the 8th century A.D.), and an Irish epic, "Táin Bó Cuailnge" (perhaps 12th-14th century A.D.), and used social network analysis to see if real events might be behind any of them.

They found the characters in the Iliad and Beowulf were consistent with people in social networks; Táin less so.

Then they took works of unambiguous fiction and used the same analysis and found differences, but perhaps a hint about what makes great fiction.

The researchers are applied physicists, not humanities academics, and this kind of research is not necessarily embraced by all humanities scholars.

They started by sitting down and reading each work, said Padraig Mac Carron, a graduate student and lead author of the study.

Besides the three fables, they studied Victor Hugo's "Lés Miserables," William Shakespeare's "Richard III," J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Fellowship of the Ring" from the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the first of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter books. They then marked each character and the characters with whom they interacted. The algorithms are from social networks, a relatively new field of computational science.

"A network is a group of nodes, and each node can be linked to another node and that is called an edge. An edge links nodes. In social networks, the nodes are represented by people and an edge is an acquaintance or some form of friendship," Mac Carron said. The number of links is called a degree.

"In Facebook, the number of friends you have would be your degree," Mac Carron said.

They marked every node, edge and degree. Some books took a day, some took weeks to get into the database.

Other scientists doing similar work just upload the text into a computer, but Mac Carron said he and his advisor Ralph Kenna thought doing it by hand was more effective.

First they tackled the three legends, marking each character to see how popular they were by measuring links and degrees throughout the whole work. They found 74 characters in "Beowulf," 404 in the "Táin," and 716 in the "lIliad."

They also measured whether the links were friendly or unfriendly, something a computer would have problems doing, Mac Carron said.

Then the researchers checked assortativity, the tendency of one character of a certain degree to interact with characters of similar degrees, a measure of popularity. They looked at vulnerability, which meant if you took that character out of the story does the story collapse?

They found in the "Iliad" and "Beowulf" that the tales followed the same patterns found in real social networks, indicating they could be based on facts or might be based on real characters, embellished over time. In the case of the Irish story, the storytellers probably were combining characters.

The use of this kind of computer analysis is controversial in the humanities, part of an academic culture clash.

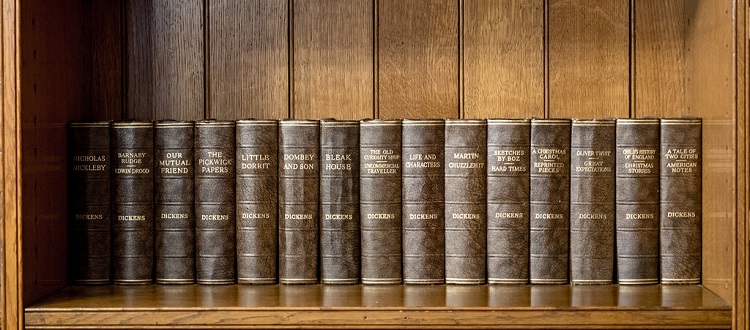

David Elson and a team of researchers from Columbia University's computer science and English departments, developed social network analysis tools for 19th century English novels, such as the works of Charles Dickens and Jane Austen. They found their interpretation of the relationship between characters differed from conventional analysis.

"There's a flood of literature that's becoming machine-readable for the first time," said Elson, who now is at Google. "The amount of literature out there even in a single genre or historical period is far greater than what any critic could read in a lifetime. Computer-aided work on literary analysis is a way we can find insights into our literary heritage and our culture at large, without giving up the 'close read' for the texts we want to look at more deeply."

Joseph Nagy, an English professor who specializes in folklore at UCLA, said he wasn't surprised with the findings.

"Myths may be inspired by historical realities or reanimated by them," Nagy said. "It's a two-way street, but myths are not distorted, poorly understood, or misremembered history."

They are, scholars think, telling us what we want to hear, which may explain what Mac Carron and Kenna found.

Even the ancient singers, who told the stories of Achilles and Beowulf before they were written down, understood social networks long before computers and algorithms, said Timothy Tangherlini, professor of folklore at UCLA who specializes in Nordic epics. They tinkered with the tales to please their audience.

"They validate tradition," Tangherlini said.

For instance, the stories are jammed with complex genealogies, but many of them may have been invented by the singers to please sponsors, some of whom wanted to be related to heroes. Over time, they may have been incorporated into the text.

Verisimilitude was demanded; that's what the audiences wanted to hear, and the best singers aimed to please.

Mac Carron and Kenna are heading to South America to do similar analysis of local myths.

The article will be published in the journal Europhysics Letters.