Mauna Kea’s Observatories Brace for Hurricane Lane

Humpback_Whale/Shutterstock

(Inside Science) -- Shops and restaurants have been shuttered. Locals and tourists alike are battening down the hatches as Hurricane Lane, a Category 4 tropical cyclone, sweeps across the Hawaiian Islands this week.

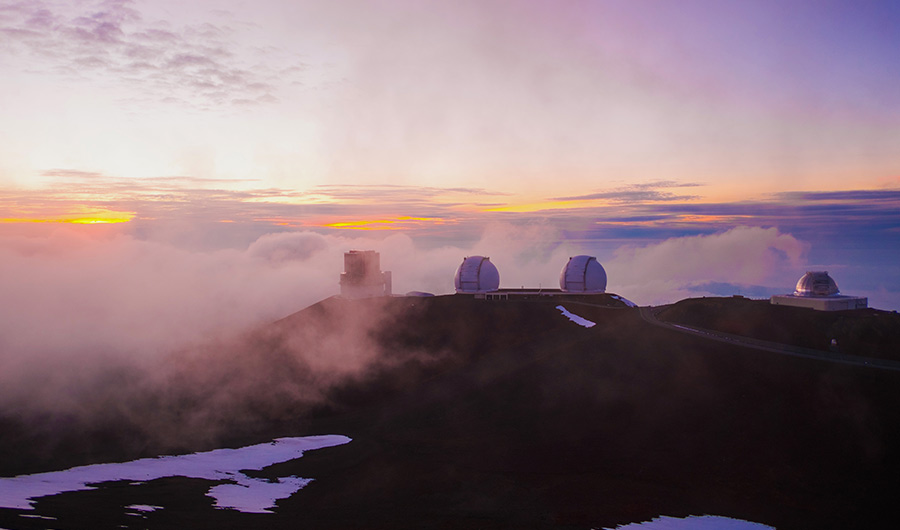

So, too, will operators of some the world’s most powerful optical telescopes. Piercing the sky at 13,796 feet, a vast array of observatories sits atop Mauna Kea volcano, the tallest mountain in Hawaii. The telescopes look like mushrooms speckled across the barren mountaintop; white and bulbous, they are responsible for charting the stars and answering some of science’s most pressing questions.

At the famed W.M. Keck Observatory -- which uncovered a galaxy composed solely of dark matter and tracked atmospheric changes on Jupiter’s moon Io, among other discoveries -- it’s Erin Petrosian’s job to ensure that the staff is safely evacuated and the premises are secured.

During the harsh winter months, the staff will typically monitor current weather conditions outside before making the decision to evacuate. But evacuating for hurricanes is different. “We use forecasting a lot more heavily than actual conditions because obviously if actual conditions deteriorate too late, we waited too long,” said Petrosian, who is the observatory’s environmental health and safety officer.

Several of the instruments at the observatory are cooled with cryogenic liquids. Petrosian’s team is responsible for filling those reservoirs so that the delicate machinery stays cool throughout the storm. They board up doors and windows, check fuel levels for the generators and prop open the doors to the computer room so the observatory’s many computer servers don’t overheat.

As Hurricane Lane creeps closer to the islands, it’s the wind that concerns Petrosian. The peak often faces winter storms that carry wind gusts between 75 and 100 mph. While the observatory is primarily built to withstand winds that streak down from the north, Hurricane Lane is approaching from the south.

For storms that come from the south, Petrosian's team has to think about the best way to orient the telescope. “We'll park it in a position so that if drips come through any seams in the dome, it's less likely that it'll drip onto the primary mirror, which can compromise the optics,” she said.

More Storms to Come for Hawaii?

In Hawaii, hurricanes like Lane are an anomaly. Conditions usually aren’t right for hurricanes to form in this part of the Pacific, which is typically dry, cooler, and has high wind shear. Only two major hurricanes have made landfall in the Hawaiian Islands in the last 60 years. Most recently, in 1992, Hurricane Iniki swept across the Pacific. Hurricane Dot made landfall in 1959. Both of those hurricanes registered as Category 4 storms.

Hurricanes need two main ingredients to form: warm seawater and calm winds in the upper atmosphere. As they move across the ocean, they gain energy from the churning waters below. It’s not just the surface temperature that has to be high: The top 300 meters of the ocean has to be warm enough to power the cyclone. High winds in the upper atmosphere affect the rotation of the storms. If the winds are too strong, they can essentially tear the storms apart.

“In the future, we're seeing an increase in the warmth of the ocean, so that's more energy for these tropical cyclones to extract -- a bigger reservoir of energy,” said James Done, an atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Some of these factors are easier to predict than others.

“We're still unsure what these upper level winds are going to do, particularly on a regional scale,” Done said.

Human-induced climate change -- caused primarily by the burning of fossils fuels and subsequent release of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere -- is reshaping how hurricanes form in the central Pacific. As the atmosphere warms, so do the oceans. While climate change is generally expected to lower the number of tropical cyclones that occur worldwide, a 2013 study published in the journal Nature predicted that the percentage of hurricanes to impact Hawaii in the coming decades will increase.

In addition to climate change, another factor that could lead to such an increase is the Pacific Meridional Mode, a naturally varying climate pattern that influences sea surface temperature, precipitation and wind direction in the Pacific, said Hiroyuki Murakami, one of the Nature study's authors and a climate scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Princeton, New Jersey.

Murakami's models also suggest that the wind current many storms follow will travel farther north, and easterly winds will become stronger. If that happens, then the storms that would have previously stuck to the west coast of the United States and Mexico will instead branch out into the Pacific.

Petrosian said the W.M. Keck Observatory is beginning to map out how a projected increase in the frequency of tropical cyclones will impact operations at the observatory. At the facility’s headquarters just below the summit, plans are in place to install shatterproof window panes. Additionally, they plan to bolster the insulation at the facilities and reseal the rubber in the domes and shutters to prevent future leaks.

How have other telescopes fared in foul weather?

Hurricane Maria's devastating 2017 sweep across Puerto Rico damaged the Arecibo Observatory. Edgard Rivera-Valentín, a planetary scientist now at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas, was part of a skeleton crew tasked with monitoring the radio telescope as the hurricane passed overhead. He and his colleagues boarded windows and mopped water that pooled in the offices. They also worked to secure the telescope’s platform, which hangs above the satellite dish.

“What we did to prepare a 900-ton platform and a 305-meter dish would be very different than the optical telescopes in Hawaii,” said Rivera-Valentín.

Unlike the telescopes in Hawaii, the Arecibo satellite dish is not shielded from the elements underneath large domes. Because the platform is suspended in the air, Rivera-Valentín and his colleagues loosened the tension on some of the telescope’s cables so they wouldn’t snap in the wind. It didn't work, though. The winds were too strong, and some of the cables snapped, dislodging equipment. The primary instruments ultimately escaped destruction, but a smaller dish was heavily damaged.

“It was entirely terrifying,” Rivera-Valentín said of witnessing the storm’s devastation. “I’m really hoping that doesn’t happen to Hawaii.”