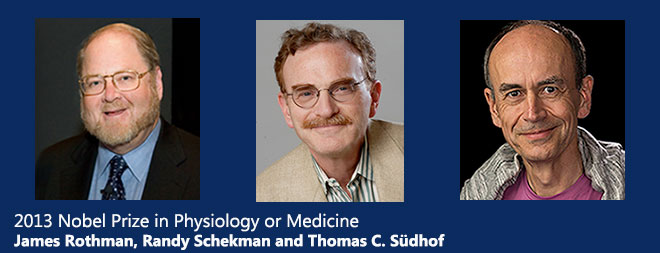

3 Share Nobel Prize For Cell Machinery Discoveries

Yale University (left), Berkeley (middle), and Stanford University (right); composite image by Lalena Lancaster.

(Inside Science) -- The 2013 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine has been awarded to three cell biologists, two American cell biologists and a German biochemist, for "machinery regulating vascular traffic, a major transport system in our cells."

The prize goes jointly to James Rothman, from Yale University, Randy Schekman from the University of California, Berkeley, and Thomas C. Südhof from Stanford University, for developing the molecular principles behind the way the cargo within cells are delivered to target areas at the right time, based on genetic and molecular machinery housed within small bubbles within cells, called vesicles. This fundamental process occurs in all cells and has implication for diseases such as diabetes and neurological disorders.

The three men worked independently over the years, but their work overlapped and synchronized into a view of the cell’s transportation system, a kind of cellular FedEx, which can transport molecules around inside a cell or deliver them to the outside efficiently and correctly. The cargo has to be delivered to the right place at the right time or the result is chaos.

The transport -- the delivery truck -- is called a vesicle, a bubble surrounded by a membrane.

Every time you think a thought, vesicles have delivered the right molecules to the right place, from one nerve cell to another. Every time a hormone is delivered to your body, it rode in on vesicles.

"Before Schekman and Rothman, we had no idea what moved things around inside a cell or how it actually worked. Their broadband approach saw a beauty and elegance--we could actually see these things happen," said Michael Marks, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. "They discovered the genes and figure out how [the genes] do it."

Schekman, a native of St. Paul, Minn., studied at the University of California at Los Angeles and Stanford, and now is professor in the department of molecular and cellular biology at the University of California, Berkeley and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Schekman, using the well-known genetics of yeast as a model, worked out how the transportation system was organized. Of particular interest to Schekman was what happened when the system went awry and the delivery system broke down. In some cases, traffic jams blocked transportation, and Schekman found the cause was genetic. He identified three kinds of mutant genes responsible.

How does the cell guarantee delivery to the right address?

Rothman, a native of Haverhill, Massachusetts, has degrees from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and is chairman of the department of cell biology at Yale in New Haven, Conn.

While Schekman was studying yeast, Rothman was doing the same with mammalian cells. He discovered a multitude of proteins that make sure the vesicle docks with the target membranes and only the target membranes, whether inside the cell or through the cell’s outer membrane. In other words, that the delivery was made to the right address.

The discovery by the two men showed that the system was the same in mammals as well as in simple organisms, which means it was set up early in the history of life on Earth.

Meanwhile, Südhof was working on timing -- when the delivery is supposed to be made.

A native of Göttingen, Germany, he studied at the Georg-August-Universität in Göttingen and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, where he worked with two other Nobel Laureates, Joseph L. Goldstein and Michael S. Brown. He also is an investigator at HHMI and now is professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford.

His specialty is nerve cell communication, the transfer of molecules from one nerve cell to another. Neurotransmitters, which carry the needed information between cells will only release the needed molecules at exactly the right time. Südhof found that the trigger was calcium ions.

If this ancient and complex system breaks down, the result in humans can be anything from neurological and immunological disorders to diabetes.

Rothman, in an interview with Nobel Media, said the key was to think about the system as machinery.

“One of the major lessons in all of biochemistry, cell biology and molecular medicine is that when proteins operate a subcellular level they behave as if they were a mechanical machinery. It’s absolutely fascinating,” he said.

He said that when someone is in the field as long as he was, he sooner or later learns if he is on the short-list for a Nobel.

“But to actually win it is an out-of-body experience,” he said.

Schekman, also in an interview with the Nobel’s website, said he was slightly primed for the announcement because he had recently won another award and people kept asking him about the forthcoming Nobel announcement. When the telephone rang early Monday morning, his wife said, “Well, there it is.”

He said he used a classical analytical technique while Rothman used more of a biochemical investigation. The two men were aware of each other’s work and Schekman said they did their research “sometimes collaboratively, sometimes competitively.”

Südhof was driving in Spain when the Nobel committee’s Adam Smith reached him by phone.

“Oh my God. I thought it was a friend calling because I’m lost,” he said.

He was pleased to share the award with the other two, he said. “It is incredibly fair.”