BRIEF: First Tree-Dwelling Birds Died with the Dinosaurs

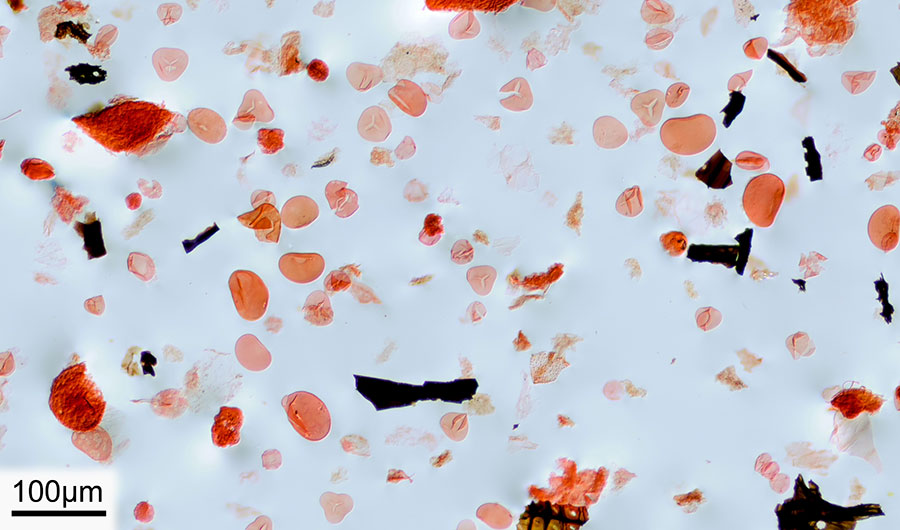

These fossilized, microscopic fern spores helped scientists connect the destruction of the planet's forests about 66 million years ago to the extinction of the first tree-dwelling birds.

A. Bercovici

(Inside Science) -- The Age of Dinosaurs ended about 66 million years ago, likely from a cosmic impact that unleashed more than a billion times the combined energy of the atom bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now scientists find this disaster not only devastated dinosaurs, but also wrecked forests and wiped out tree-dwelling birds.

The researchers analyzed microscopic plant fossils. After catastrophes such as wildfires, ferns are usually the first plants to come back, because they sprout from spores, which are each just a single cell. Seeds are far larger and so can't disperse as far, explained study co-author Antoine Bercovici, a paleobotanist and sedimentologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History.

After the cosmic impact, the fossil record from New Zealand, Japan, Europe and North America is loaded with the charcoal remains of burnt trees as well as tons of fern spores, hinting at mass deforestation the globe took centuries or even millennia to recover from. And with no more trees, the scientists found the first birds to dwell in trees likely went extinct.

Birds evolved from other dinosaurs before the mass extinction. The researchers suggested that all birds alive today are descendants of a handful of ground-dwelling species, avians whose fossilized skeletons possessed the longer, sturdier legs seen in modern ground birds such as kiwis and emus. The ancestors of modern birds likely did not move into the trees until the forests recovered, said study lead author Daniel Field, a vertebrate paleontologist and evolutionary biologist at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath in England.

Birds are now the most diverse and globally widespread group of terrestrial vertebrate animals, with nearly 11,000 living species. These findings not only shed light on how modern birds arose, but "they also shine a light on the devastating impact of mass deforestation on biodiversity," Field wrote in an email to Inside Science. "There are important implications for conserving forest ecosystems in the modern world."

The scientists detailed their findings online May 24 in the journal Current Biology.