BRIEF: Mining May Threaten Newly Discovered Ocean Ecosystems

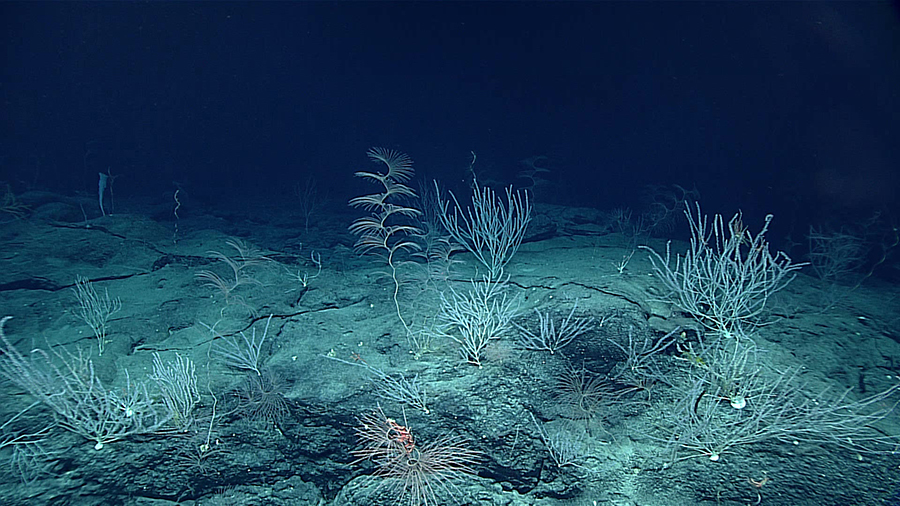

A dense field of corals grows on a metallic crust covering Pigafetta Seamount in the North Pacific Ocean.

(Inside Science) -- In 2003, researchers discovered a never-before-seen biological world: vast forests of sponges and corals growing on the metal-encrusted peaks of mountains submerged deep in the sea. Now, researchers are scrambling to document these unknown ecosystems before mining operations start grinding some of them into rubble.

The ecosystems in question grow on seamounts known as "guyots," which have flat tops at least 200 meters below the surface. Many guyots develop metallic crusts made mostly of manganese and iron. At three such places, past expeditions discovered many animals such as corals, lobsters, sea stars and fish living close together -- a rarity in the deep ocean.

Last week at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, researchers presented preliminary findings from an ongoing National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration project to explore U.S. Pacific Monuments. One of the project's goals was to search for more animal communities on ferromanganese crusts. Two years into the three-year project, they have already found more than a dozen additional sites teeming with hundreds of different kinds of animals, which the public can admire through videos on the Okeanos Explorer website.

"We found some marvelous communities," said Christopher Kelley, program biologist for NOAA's Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory at Manoa and one of the expedition's leaders. "Each one is different."

The only other known examples of dense deep-sea animal communities are at sites such as methane seeps and hydrothermal vents, where life can get energy from organic chemicals rather than sunlight. But even though they live in darkness, crust communities ultimately get their energy from the sun, feeding on organic matter that drifts down from above. This rain of food is scarce across most of the ocean, but researchers suspect that rapid currents bring more of it to crust communities. Nevertheless, the limited food supply probably means that crust communities grow slowly, says Scott France, a biologist at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and another expedition leader.

Most of the ecosystems the researchers discovered are protected, but not all similar communities are so lucky. Mining companies have long been interested in ferromanganese crusts, especially on the relatively accessible flat tops of guyots. The International Seabed Authority granted the first mining permits to China and Japan in 2013, and since then, Korea and Russia have also received permits for exploratory crust mining. Kelley fears that such actions are premature. Before leasing out seamounts, he says, people should map out the areas, learn where animals live, and get some idea of what the world stands to lose.