The Evolution of Valentine's Day

gpointstudio via Shutterstock

(Inside Science) -- Every February 14, America's romantic drives are transmuted en masse into chocolates, jewelry and fancy dinners. How do marketers achieve this remarkable feat? According to evolutionary psychologists, they do so by tapping into deep-seated patterns of thought and behavior that predate Hallmark, and perhaps humanity itself, by thousands or millions of years.

Evolutionary psychologists view human behavior as the expression of mental traits that helped previous generations reproduce. For example, imagine that an early human named Thag had genes that made him want to mate, while his neighbor Ug did not. Thag would probably father more children, and his children would inherit those mating genes, making the future of humanity slightly more Thag-like than Ug-like. Such an evolutionary lens can help scientists make predictions about modern society, from when people are likely to cooperate to which children are at greatest risk of abuse.

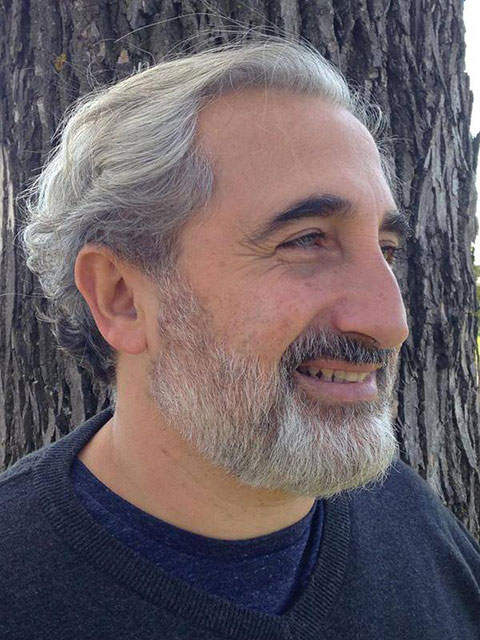

Gad Saad, an evolutionary psychologist and professor of marketing at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada, uses this evolutionary approach to study how and why people buy things. He writes the Psychology Today blog "Homo Consumericus," and he is the author of several books, including "The Consuming Instinct: What Juicy Burgers, Ferraris, Pornography, and Gift Giving Reveal About Human Nature." In this edited interview with Inside Science, Saad explains how expressions of romance in American culture, particularly in heterosexual relationships, may be less arbitrary than they seem.

INSIDE SCIENCE: Can biological evolution offer any insights into a cultural phenomenon like Valentine's Day?

GAD SAAD: Ultimately, the Valentine's ritual is one in which all of these Darwinian imperatives are manifesting themselves. I mean, it's a marketer-created event, but that ultimately pulls at our Darwinian strings. It's an opportunity for our mating rituals to manifest themselves. And so from that perspective, then, it makes sense to study that phenomenon. …

You may or may not know of all the studies that have looked at the so-called red effect. Does that ring a bell?

IS: Please tell me.

GS: As we know, typically, women redden their various -- you know, they put blush, they put red on their lips. The stilettos are red colored. Lingerie is red. The association with Valentine's is red. And so the argument then becomes, why red? What's so special about red?

And there are some incredible studies that have shown that if you take the exact same woman, and you either associate her with the color red or not, and you ask men to rate how beautiful she is, they will rate her as more beautiful when she is associated with the color red. Let's say there is a red background. Well, the woman hasn't magically changed, right? Her morphology hasn't changed. But she's viewed as more beautiful. …

Now, the argument -- a speculative one, but a compelling one -- the argument is that what this is doing is that it's mimicking the arousal, the reddened arousal that we see sexually in particular regions, that you see in other animals as well, right? So, say, in other primates, you have an engorgement and an enlargement of the genitalia during [fertile periods]. And so one argument why red becomes so important during Valentine's is that it's playing on this very basic sort of color connotation.

IS: Some people hearing that might think, "well, I don't think I'm looking at genitals when I see a woman in a red dress." How would you answer them?

GS: Right, well, I think that it's piggybacking. It's not so much that we've evolved a penchant for red stilettos. It's that that color is something that we innately associate with something, and then this ritual piggybacks on it.

IS: So what about giving gifts to your romantic partner? How might that have evolved?

GS: In 2003, I had published a paper with one of my former doctoral students where we looked at the motives that men and women give gifts to one another. And we broke up those motives into two types: into tactical motives, and situational motives. Tactical motives would be "I give gifts with my partner to have sex with her." … Situational would be, you know, "I give gifts when it's his or her birthday. The situation demands it."

And what we found is that when it comes to situational motives, there were no sex differences. In other words, men and women equally give gifts for situational reasons. But tactical reasons -- men were much more likely to use them. In other words, men use gift-giving with an ulterior motive, or to communicate something. To communicate generosity, to communicate wealth, to communicate my interest in you. …

If you then ask men and women "why do you think the opposite sex gives you gifts," here you get an incredible finding. Men think that the reason why women give them gifts is the same reason why they give gifts to women. So if you give me a gift, it's because you're trying to have sex with me, from a male psychology. Whereas women are blatantly aware that the reason why men give them gifts is different than why women give men gifts.

And so then the question is, well, why are women so capable of understanding the dynamics of the situation, but men are somehow blissfully unaware? And so we speculate here -- this was a post-hoc speculation after we saw the data -- that there is no evolutionary reason for men to be able to understand the dynamics of the situation. I mean, who cares, right? If you lie to me -- if you come to me and say "here's a flower, I'll be with you forever, now let's go behind the shed and have massive sex" -- and you're lying to me, great! Please introduce me to as many women as possible who will lie to me this way. On the other hand, if women were as easily duped by the duplicity of that approach, then they very quickly lose, you know, the judicious nature of their mate choice.

IS: Why is it so important for women to be able to know the motivation of a man giving them a gift?

GS: Right, so, here there are two evolutionary principles at work. Parental investment theory is a theory that was proposed by [Rutgers anthropologist and evolutionary biologist] Robert Trivers that basically says that if you want to understand sex differences within any species, simply look at the minimal obligatory parental investment that is required of each sex. Now, for most species, it is much more weighted toward females. And that certainly is the case for humans. Even though human males are really good dads compared to other mammalian species, we still don't invest as women do in terms of a minimal obligatory investment. Therefore, we would expect that the cost of making a sub-optimal mate choice looms much larger for women than it does for men. They have to be more judicious in their mate choice.

But -- and here's the but part -- in some cases, women are shopping for good genes. That's a short-term mating pursuit. In that case, they might actually not care whether the man is going to stick around or not. For example, when women cheat on their long-term partner, they typically cheat with a man who is of superior genes.

IS: How might these different pressures that men and women face, based on how much they have to invest in a child -- how might those shape other aspects of gift-giving behavior?

GS: When it comes to Valentine's, I mean, yes -- it is a tango between a man and a woman. But it's really an opportunity for a man to exhibit all of those characteristics that women desire: attentiveness, generosity, and so on.

IS: Is there anything about Valentine's Day that presents a puzzle or a surprise for an evolutionary psychologist?

GS: I could answer on a personal level, and this may not be relevant for your article. But I don't usually like to have some external agent ask me to participate in a ritual, you know? … I don't like the idea that there is a marketer-determined day on February 14th where I'm supposed to exercise this Darwinian imperative.

IS: Do you have any insight into how we might have gotten there? If we have these biological, psychological tendencies that make it so that we're going to be engaging in these behaviors anyway, how did we end up with a specific day when someone else is telling us we have to?

GS: A good marketer is one who doesn't go against human nature, right? And so therefore, whether they do it consciously while realizing what they're doing, or they do it instinctively without knowing the fundamental ultimate cause, they are in the business of trying to find ways to get you to spend. And so it's not difficult. You don't have to be, you know, the president of [the Human Behavior and Evolution Society] to understand, "hey, if I can create a day where I can get you to celebrate this very basal mating ritual, it's likely to work." And guess what? It does.

IS: What kinds of reactions or objections would you expect people to have to the way that we've been talking about Valentine's Day?

GS: People have a disdain of imagining that some of the things that they do, and in this case something as wonderful as sort of celebrating the love that you have for each other, could be explained by 'vulgar biology,' right? Somehow it removes the mystical nature, the mystery of love, if you somehow vulgarize it by explaining that 'here is the fundamental biological reason why you're doing this.' Of course, it doesn't. I mean, the love that I feel for my wife doesn't suddenly disappear or get cheapened if I also explain the evolutionary reason why romantic love has evolved.

By the way, romantic love, in case you don't know, evolved precisely because we're a bi-parental species. I mean, if you need to have a male and a female stay together long enough to successfully rear children for many years, then you'd want them to evolve the emotional system that permits for romantic love to evolve, right? I'd need to have that romantic bonding mechanism with you so that I can stick around long enough. For a species where you don't have bi-parental investment, then you don't expect this bonding mechanism to occur.

Now, the fact that I just explained this doesn't take away from the magic that we actually experience when we fall in love with someone.