Gargantuan Black Hole Discovered in the Young Universe

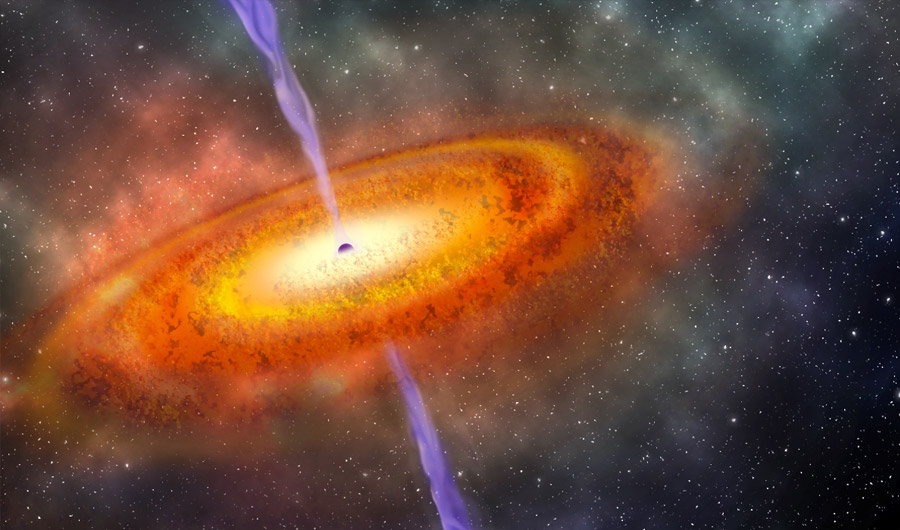

Artist’s conception of the most-distant supermassive black hole ever discovered, which is part of a quasar from just 690 million years after the Big Bang.

Robin Dienel, courtesy of the Carnegie Institution for Science.

(Inside Science) -- Black holes are a bit like children -- the older they are, the more time they have to grow big. But in a rare find, astronomers have just discovered a colossal black hole that’s, cosmically speaking, still a youngster. Weighing in at about 800 million times as massive as our sun, it presents a puzzle to scientists trying to figure out how it could have grown so big so fast.

The so-called “supermassive” black hole is the most distant such object ever observed, which means it dates back to the universe’s early years. It powers an extremely bright quasar, a luminous and remote celestial object that emits enormous amounts of energy, which is how astronomers searching for such quasars with the Magellan Baade telescope in northern Chile were just barely able to spot it in the middle of a galaxy. The black hole reached its enormous size when the universe was just 690 million years old, only 5 percent of its current age. The team published their work in Nature on Dec. 3.

“These [black holes] are super rare. There could be between 10 and a hundred in the whole sky, and the universe is big, so this is really like finding a needle in a haystack,” said Eduardo Bañados, lead author of the study and an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Pasadena, California. “People have been looking for objects like this for decades.”

As long as matter like gas, dust and stars from the host galaxy keeps getting pulled into such a black hole, it gives off bright light in the form of a quasar -- in this case as dazzling as 40 trillion suns. But once the fuel runs out, it shuts off, making the discovery all the more fortunate.

Scientists expected that such a giant black hole would have needed a longer time to develop. The very first galaxies could have assembled when the universe was 180 million years old, meaning this black hole and others like it in the early universe would have had little time from a cosmic perspective to become such behemoths.

“One possibility is that these black holes were born small and grew up rapidly while ingesting vast amounts of material, eating a lot in a short time,” said Rosa Valiante, an astrophysicist at the Astronomical Observatory of Rome, who was not involved in the study. But the supply of gas is limited, and black holes can only devour it so fast.

“The black hole can’t swallow everything. The matter that’s falling in heats itself up and radiates, but this radiation pushes the gas away, so there’s a maximum rate you can force-feed it,” said Tiziana DiMatteo, an astrophysicist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh not involved in the study.

A less extreme alternative is that the black holes were born big and then continued to grow, Valiante said.

Yet another possibility is for already massive black holes to crash into each other, joining to make an even bigger one. The European Space Agency’s Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, planned for launch in 2034, would detect gravitational waves generated by these first black hole collisions, if they indeed collided that early in cosmic history.

In any case, the young yet massive black hole would have needed just the right conditions to develop, such as possibly being in the densest part of the early universe, which would have given it more material to feed on. Astronomers hope to better understand how such enormous black holes could form quickly by searching for more of them, along with distant galaxies, with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in spring 2019.

Bañados and his colleagues also found that their black hole formed among a large quantity of neutral hydrogen gas, with electrons balancing protons. But this gas was gradually becoming ionized by bubbles of energetic radiation from the first stars, galaxies and quasars that stripped electrons away from protons. The scientists’ analysis shows that this ionization process completed slightly later than previously thought, probably when the universe was a billion years old.

The black hole’s host galaxy also turns out to be a conundrum on its own, according to a companion study published in the Astrophysical Journal and led by Bram Venemans of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. The researchers found that the galaxy contains plentiful dust and gas as well as heavy chemical elements that only could have formed from multiple generations of stars. As with the black hole, this means the process must have started early and gotten going fast.

“It’s amazing what you can learn about the early universe from this one object only. Now we want to find more! It’s good for our morale,” Venemans said.