Male Guppies Try to Swim Through Walls; Females go Around

A female guppy ponders her next move in a complex maze task.

Tyrone Lucon-Xiccato

(Inside Science) -- Male fish are better than females at navigating a complex maze, but they flounder when faced with a simple transparent wall, according to a new study. The findings may indicate that females take a more flexible approach to solving problems, whereas males try to power through using sheer persistence.

"When the barrier was transparent, we found that females were much faster than males to perform the task," said Tyrone Lucon-Xiccato, a biologist at the University of Padua in Italy and first author of the study, which was published Nov. 19 in Animal Behaviour. "Males were getting stuck … persistently trying to pass through the barrier instead of detouring around it.”

The researchers hadn’t planned to test guppy persistence. Instead, they set out to test a well-established theory about how males and females evolve different spatial skills.

In monogamous species such as prairie voles, males and females live similar lifestyles, and they tend to be equally good at spatial tasks. But in most species, successful males mate with many females, and that means they have to travel.

"Males, in a way, are competing with each other spatially -- you know, who can patrol the largest home range and encounter the most females," said David Sherry, a behavioral neuroscientist at Western University in London, Ontario, who was not involved in the study. "You'd expect sexual selection to favor males who have good spatial ability."

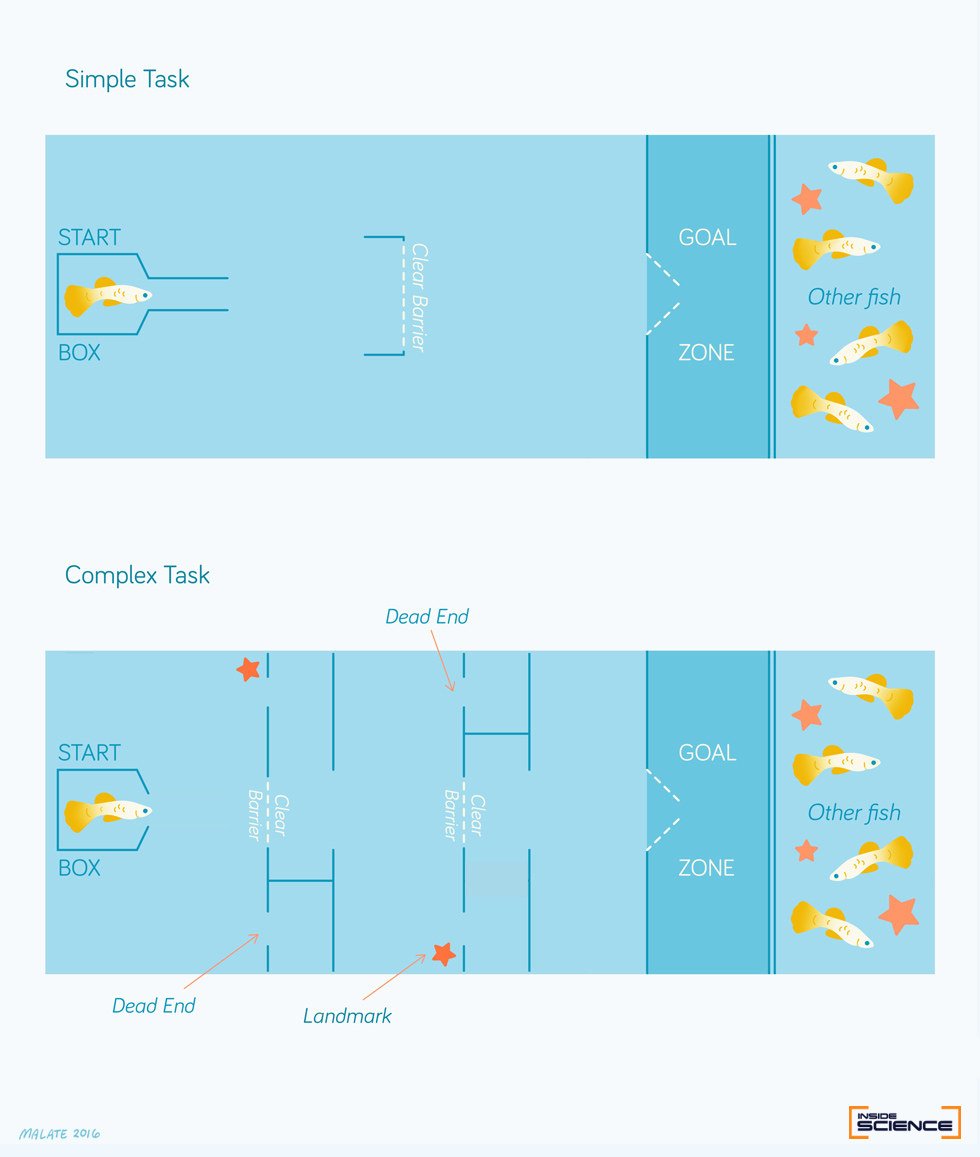

In humans and many other mammal and bird species, males do tend to roam farther and have better spatial skills. To find out whether the same holds true in fish, the researchers turned to guppies, a species in which males mate with as many females as possible. Male guppies travel more than females, often moving to new pools in the river. They also spend more time close to shore, where there are plants and other landmarks to use for navigation. The researchers suspected that males' wide-ranging habits and complex environments would favor keen spatial skills. To test this prediction, they designed two navigation tasks -- one simple, and one complex -- and presented each task to 24 males and 24 females.

In the simple task, fish were presented with a clear plastic barrier, with short side walls to prevent them from slipping around by accident. The barrier let them see a group of other guppies, which the lonely fish wanted to join. When the transparent barrier was covered in mosquito netting to make it visible, males and females navigated the obstacle with equal ease. But when the barrier was completely clear, the average male spent nearly eight minutes just pushing against it, while the average female found her way around in under two minutes.

The researchers don't know why males struggled with the clear barrier, but they suspect it has more to do with persistence than spatial skills. They already knew that male guppies can be stubborn, thanks to a prior study in which guppies nudged aside one of two colored discs to find food. In that study, when the researchers switched which color concealed food, females were quicker to learn that the rules had changed. Similar studies in rats, chickens, and monkeys have also highlighted male persistence and female flexibility. The researchers speculate that persistence may help males overcome female reluctance to mate.

These ideas about persistence are plausible, said Sherry, and they call for further study. Enrique Font, an ethologist at the University of Valencia in Spain who was also not involved in the project, agrees.

"There might be some alternative explanations," he said. "They should perhaps try to do more experiments addressing that particular issue -- the difference in persistence between males and females."

While the simple task raised intriguing questions, the complex task gave answers, confirming predictions that males would do better in a difficult maze. In the complex task, guppies had to find their way past two barriers, each of which had a transparent panel and two doors. Males quickly learned which doors led to dead ends, and which led toward the other guppies visible through the window. More than 80 percent of males went straight for the correct doors on the second attempt. Females, in contrast, never learned the route, choosing doors at random in all five trials.

The results mark the first evidence of spatial skill differences between sexes in a fish, said Lucon-Xiccato. More importantly, they match results from other species, supporting the idea that each sex’s spatial ability reflects how much it travels. This, said Font, is the real strength of the study: By extending the pattern to a new group of animals, the researchers confirm that they understand how spatial skills evolve.