New Worm Species with Jewel-Like Scales Discovered in Deep Ocean Darkness

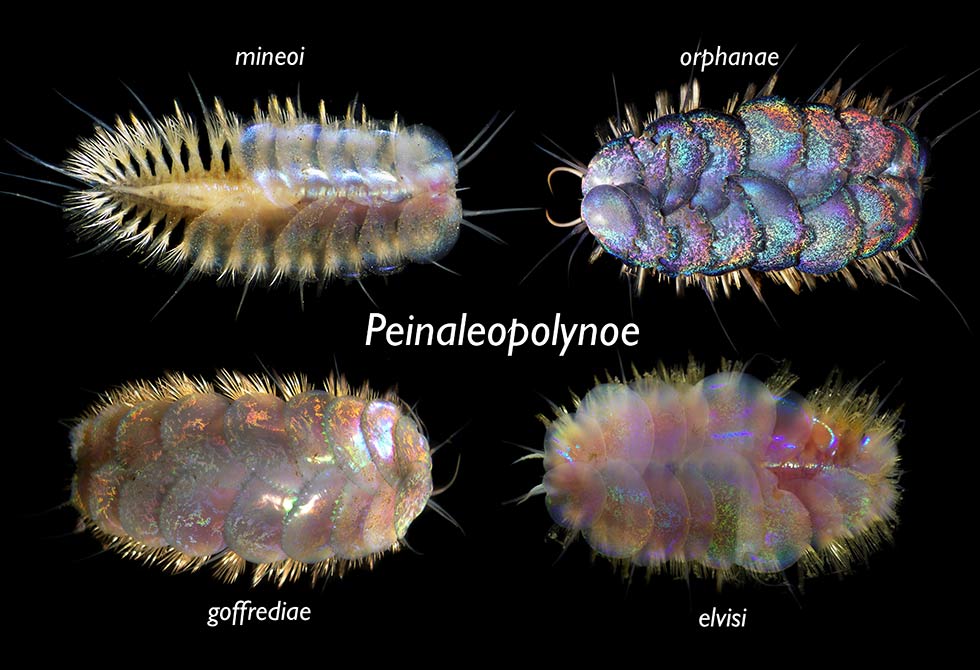

Peinaleopolynoe orphanae, one of four new species of scale worms that researchers discovered thousands of meters beneath the sea surface.

Greg Rouse

This image may only be reproduced with this Inside Science article.

(Inside Science) -- Some of the most brilliant colors in the animal kingdom belong to worms that live in the dark and have no eyes.

Researchers described four new species of deep-sea worms in a paper published today in the journal ZooKeys. They have been collecting the worms for years, but only recently teased apart their species relationships using genetics.

"Our nickname for them was Elvis worms because they look like sequins on an Elvis jumpsuit," said Greg Rouse, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

The new species are Peinaleopolynoe goffrediae, named for marine biologist Shana Goffredi; P. mineoi, named for the father of biotechnologist Chrysa Mineo, who helped fund the research; P. orphanae, named for geobiologist Victoria Orphan; and P. elvisi, whose name is self-explanatory. They belong to a group known as scale worms, distant relatives of earthworms that are covered in large, overlapping plates.

Most specimens were found clustered around the carcasses of whales and other sunken organic matter, although P. orphanae was also found at a hydrothermal vent, said Avery Hatch, a graduate student in Rouse's lab and one of the scientists who conducted the research.

Hatch's favorite part of the worms lies beneath the scales: intricate branching structures that serve as lungs. Hatch and her colleagues suspect these lungs evolved to be large and complex so the worms could survive in low-oxygen environments. The scales themselves come in iridescent shades of pink, blue and purple. Tufts of golden bristles on the animals' feet add extra sparkle.

For human eyes only?

Can anything down there actually see the worms' shimmery colors? No one knows, and opinions are divided. The worms themselves have no obvious eyes, although it's possible they can sense light in some other way, said Rouse. All the specimens were found at or below 1,000 meters, too deep for sunlight to reach.

But the ocean isn't like cave environments, where pallid, eyeless animals feel their way through pitch blackness. Many deep-sea creatures have well-developed eyes.

"Eyes are metabolically expensive. Mother nature isn't going to mess around and give you a huge eye unless it somehow helps your survival," said Tamara Frank, a biological oceanographer at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, who was not involved in the research.

In the deep sea, the main light source is bioluminescence produced by animals' bodies. Clouds of tiny plankton organisms light up when jostled, and many fish have light-producing organs on their sides that glow in species-specific patterns. Some animals even have "flashlights" under their eyes to illuminate objects in front of them.

Elvis worms don't produce their own light as far as the researchers know. It's conceivable their iridescence could serve as a defense, causing predators with undereye flashlights to be momentarily blinded by reflections. But Frank doubts it. Predators with undereye flashlights tend to live higher in the water column, still deep but not on the bottom with the worms.

"There's just no way that's going to be visible to any animal down there," said Frank. "I honestly think the iridescence doesn't have any functional significance."

But Frank's colleague Edith Widder, a deep-sea biologist and CEO of the Ocean Research & Conservation Association, still thinks there may be organisms that can see the worms in their dark habitats. The seafloor at those depths is largely unexplored, and some of its denizens -- for example, fish known as rat-tails -- are known to produce light.

"[Frank] may be right about the likelihood of fish with flashlights, but there are rat-tails down there and they have a different kind of luminescence which oddly enough shines out their ass. We're not sure for what reason," said Widder, who was not involved with the research.

Bizarre behavior caught on camera

Rouse and Hatch agree with Frank that there is probably nothing besides humans observing the worms' colors. The colors are produced by physical structures in the top layers of the scales, and the thicker those layers, the brighter the iridescence. Elvis worms might have evolved rigid scales purely as armor, with the colors arising as a side effect.

A remarkable video from a hydrothermal vent 3,700 meters deep in the Gulf of California may help reveal why the armor is needed. Orphan was operating the camera on a remote-operated vehicle, trying to get a closer look at her namesake species, when two worms began lashing out at each other with parrotlike beaks on the ends of long proboscises.

Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

"I had seen them as these sort of passive, cute worms. But they actually were taking chunks out of each other," said Orphan.

The researchers had previously noted that P. orphanae worms have thicker, more vivid scales than the other species, and the edges of their scales tend to be notched and ragged.

"It wasn't until we saw that video of them fighting that it suddenly clicked. Like, 'Wait -- these things in the scales, these notches, are bite marks,'" said Rouse.

The whole display was unlike anything the researchers had seen before. Widder called it "stunning and bizarre." She was particularly intrigued by the dancelike scuffling motions the worms performed between lunges.

"I really want to know what that jitterbug is about," she said.