Sea Urchins Spew Personal Army of Venomous Jaws

Hannah Sheppard-Brennand

(Inside Science) -- Imagine a swarm of venomous, quivering jaws surrounding the food you are about to eat. Would you change your mind about dinner? Fish do, as it turns out. And that's good news for collector sea urchins, spiky creatures 4 to 5 inches across that live in shallow waters mostly around Australia. Collector urchins' shells are carpeted with tiny, biting appendages called pedicellariae. When threatened, the urchins release the heads of their pedicellariae en masse, creating a snapping cloud of defenders that predators are loathe to approach.

"You can see a pedicellaria head when it's just being released from the urchin, and it's, like, twitching. It's got its jaws open, with the fangs on the end," said Hannah Sheppard-Brennand, a marine ecologist at Southern Cross University in New South Wales, Australia and first author of a new study describing the phenomenon in The American Naturalist. As far as she knows, this is the first documented case of an animal releasing autonomous venom devices -- detached organs that can sense their surroundings and independently deliver their payload.

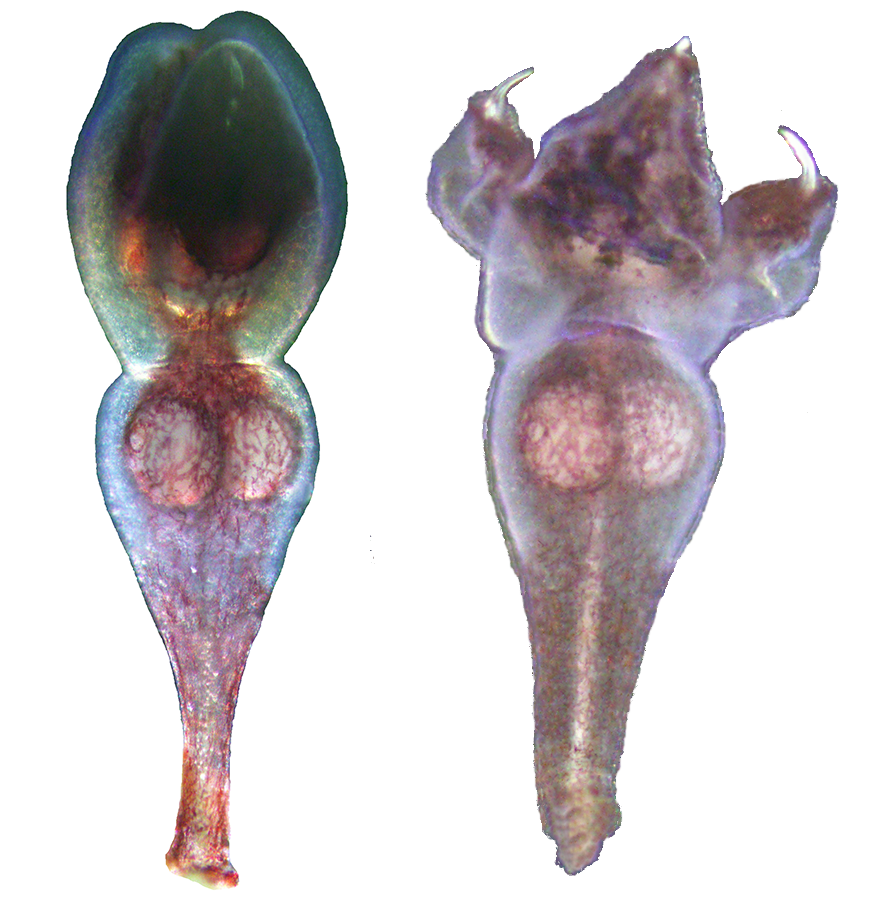

Many people are familiar with the spiny appearance of sea urchins, but most have probably never noticed the pedicellariae that grow between the spines. Each one is less than a millimeter across, and they come in several different types, some of which are more suited to cleaning away algae than fighting off predators. Collector urchins have a particularly fearsome variety of pedicellariae consisting of stalks topped with biting jaws. The three sections of the jaws open outward like flower petals, each one ending in a venomous fang. A dense forest of these structures covers the collector urchin's shell, waving and snapping in response to touch, chemical signals and looming shadows.

"They open and close in response to changes in light," said Sheppard-Brennand. "If there's contact on the [shell], then they all rotate toward that contact."

Researchers have long known that some sea urchins use pedicellariae for defense against predators. But in most species, the organs remain attached, only tearing loose after they have clamped down on an enemy. Sheppard-Brennand and her colleagues suspected that something else was going on with the collector sea urchin, a large species that is sometimes eaten by humans. No matter how gently the researchers handled collector urchins in the lab, their hands soon became covered with detached pedicellaria heads. Occasionally, the tiny jaws managed to bite human skin, often on the webbing between fingers, said Sheppard-Brennand. The bite, she said, feels like a bee sting.

Past researchers have occasionally observed that some urchins seem to lose their pedicellariae at the slightest provocation. But until now, no one had studied the behavior systematically, said Sheppard-Brennand. She and her colleagues gathered sea urchins from five species that live in the same Australian reef, then gently tapped their shells with forceps to simulate a predator attack. Four of the urchin species kept their pedicellariae, but the collector sea urchins released a continuous stream of the biting appendages. In the original experiments, collector urchins released tens of pedicellariae per trial, but in subsequent tests, which have not yet been written up and published, they spewed hundreds over the course of 30 seconds, said Sheppard-Brennand.

Even this loss doesn't leave the animals undefended, she added. Collector sea urchins have so many pedicellariae that they can lose a few hundred at a time and not look any different. The pedicellariae grow back in about 40 to 50 days, she said.

In the second part of the study, Sheppard-Brennand and her colleagues confirmed that the collector urchin's defense is effective against predators. They found that fish were reluctant to eat food with pedicellariae embedded in it, both in the lab and in the wild. Moreover, fish in the lab avoided water downstream of an irritated urchin, perhaps smelling some chemical signal that the urchin released along with its pedicellariae.

"I think this discovery that they've made is very intriguing," said Linda Weiss, an animal ecologist at the Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany, who was not involved in the study. Weiss studies anti-predator defenses, and is familiar with sea urchin pedicellariae. But she didn't know that some urchins could send their pedicellariae "swarming out as little defenders, really deterring predators," she said.

The collector urchin's unique defense could help explain its unusual behavior. While other sea urchins in the same habitat only venture out at night, collector urchins are bold enough to forage throughout the day. Perhaps, said Sheppard-Brennand, the ability to release pedicellariae gives these urchins extra protection, making it worth the risk of exposing themselves in daylight. Still, she noted, the defense isn't perfect, as collector urchins are often found in predators' stomachs.

Perfect or not, pedicellariae are amazing structures. With their twisting stalks and snapping heads, they remind Sheppard-Brennand of the tall, venomous, science fiction plant-monsters known as Triffids.

"If you ever get the chance to look down a microscope at the [shell] of a sea urchin, it's well worth it," she said. "They're so strange, and so sort of terrifying -- just on that minute scale."