Sick Plants May Attract Distant Bacteria as Medicine

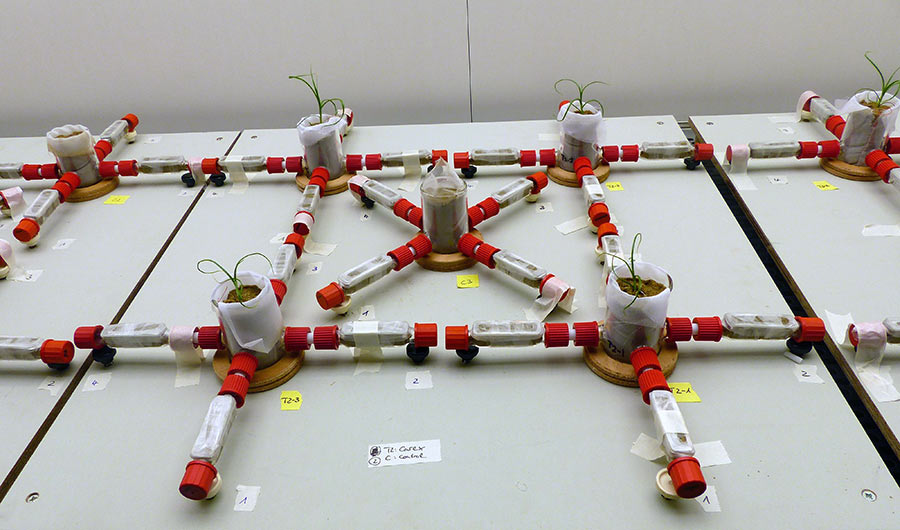

This experimental setup allows researchers to place bacteria at the ends of the glass tubes, then measure how much bacteria moves toward the plants.

Kristin Schulz-Bohm

This photo can be reproduced only with this Inside Science article.

(Inside Science) -- If there were a prize for long-distance, interspecies communication, few people would think to nominate a bacterium and a scraggly, grasslike plant. But according to a recent study, the roots of one such plant can call bacterial allies several inches away -- a veritable marathon for tiny soil bacteria. Preliminary data suggest that the plants may even adjust their messages when they get sick, calling in different bacteria to act as medicine.

Scientists already knew that plants send signals aboveground to communicate with animals. Flowers, for example, attract bees and other pollinators using color and scent. Some plants also use scent chemicals to call for help when they are attacked by plant-eating insects, luring in parasitic wasps that attack the insect herbivores.

But comparatively little is known about how plants communicate with microbes belowground. Plants rely on a complex microbiome to help them obtain nutrients from the soil, but most research on plants and soil microbes has focused on interactions that happen right at the edges of plant roots, said Paolina Garbeva, a microbial chemical ecologist at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology in Wageningen.

Garbeva and her colleagues suspected that plants use volatiles -- substances that easily evaporate and can diffuse through air and water -- to send long-distance "scent" messages belowground as well as above. In a study published this past January in The ISME Journal, they collected and analyzed the volatiles released by sand sedge roots, and then tested how bacteria responded to those volatiles.

To test the responses of bacteria, they filled glass cups with sterilized soil that contained no living bacteria, and used some of the cups to grow sand sedge plants. Each cup was connected to four horizontal glass tubes about 4 inches in length, which were also filled with sterile soil. The researchers placed a mixture of bacteria at the outer ends of the tubes, then measured how much of each strain of bacteria traveled through the tubes toward the cup.

Cups that contained plants attracted up to three times as many bacterial cells per strain as cups without plants, suggesting that bacteria were detecting the plants' presence from 4 to 5 inches away, said Garbeva. The bacteria were presumably responding to volatiles released by the plants' roots, since only volatile compounds could effectively diffuse so far through the soil, she said.

Next, the researchers infected some of the plants with a fungal disease. The infected plants released a different mix of volatiles from their roots, which in turn attracted a different suite of bacteria. When the researchers grew these bacteria in petri dishes with the infectious fungus, they found that the bacteria halted the fungus's growth, raising the tantalizing possibility that the plant was recruiting specific bacteria as medicine.

The medicine-recruitment idea is still highly speculative, noted Garbeva. She and her colleagues are currently testing whether the bacteria attracted by sick plants can effectively combat the disease on the plants themselves. They have not yet compared the antifungal properties of the bacteria attracted by sick versus healthy plants, so it's possible that healthy plants' bacteria are just as good at stopping the fungus.

Moreover, these types of ecological processes are often context-dependent, said Sergio Rasmann, an ecologist at the University of Neuchatel in Switzerland, who was not involved in the study. If the researchers were to repeat their experiments while changing something like temperature or humidity, he said, they might get different results.

Nevertheless, the results are "very exciting," said Rasmann. "The idea of plants recruiting microbes is not completely new. But the fact that they actively produce some chemicals in the soil to attract them -- that's very new," he said.

Garbeva hopes that by examining the types of bacteria plants attract in nature, scientists may someday identify strains that could be added to crops as probiotics. Different strains may help with particular problems such as disease or drought, she said.

"Soil has the highest microbial diversity in the world," said Garbeva. "We can find how plants can attract bacteria that are beneficial for them, and maybe we can use these bacteria in the future for plant protection."