The Catch-22 Of Alzheimer's Diagnoses And Treatments

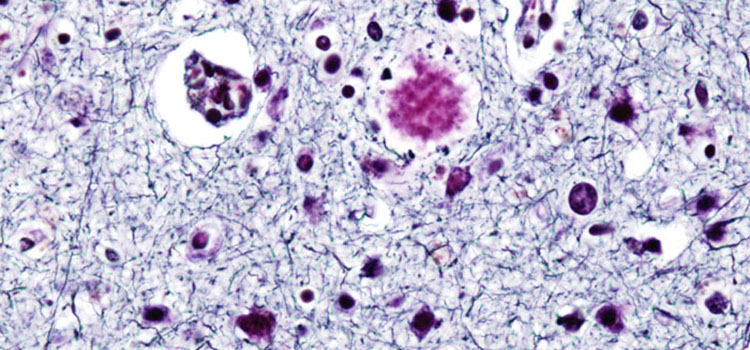

Plaques (shown here in purple) can begin to invade the brain of someone with Alzheimer's disease years before memory loss symptoms begin to show.

image via wikicommons | http://bit.ly/19K7aB0

Editors' note: This is part two of a three-part series on Alzheimer's disease and the current state of research and treatment. Part one is available here and part three here.

(Inside Science) -- One reason scientists haven't come up with a cure or treatment for Alzheimer's disease is that they don't know exactly what it is. They can see what happens to patients and predict what will happen but don't know much about the underlying reasons why the disease affects the people it does, or why the symptoms grow worse over time.

"There are lots of things we don't understand about the physiology," said Reisa Sperling, a professor of neurology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and director of the Center for Alzheimer's Research and Treatment at Brigham and Woman's Hospital.

Alzheimer's has a strong genetic factor. Genetics accounts for perhaps 80 percent of the risk of developing the disease. There are genetic tests for the three common forms of a gene called ApoE. One form of the gene increases the risk of Alzheimer's but the testing for it doesn't reveal anything useful in treatment and is uncommonly used. Having the bad gene does not guarantee you will get Alzheimer's, only that you are somewhat likelier, and there is nothing that can be done to prevent it or treat it.

Finding a cause

It is generally acknowledged that Alzheimer's is an "infectious" disease, an unfortunate way of describing its ability to spread from one brain cell to another — not that you can catch Alzheimer's from someone who has it. You can't.

One explanation, proposed most famously by Nobel Laureate Stanley Prusiner of the University of California at San Francisco, is that the infectious nature is caused by prions, the same misshapen proteins that cause mad cow disease and Creutzfeldt-Jakob. Prusiner won his Nobel in 1997 for discovering prions. A proven link would connect Alzheimer's to several other diseases.

Another interpretation is that Alzheimer's is the result of oxidative stress, the inability of the body to chemically process oxygen correctly — a decidedly minority view.

A more intriguing similarity is between Alzheimer's and type 2 diabetes, both of which involve amyloids. It is possible Alzheimer's is a third type of diabetes, but there is not yet enough evidence to support this view.

Many scientists now believe that Alzheimer's is an autoimmune disease. It involves antibodies to a fatty acid called ceramide, which is linked to amyloid. That could explain why Alzheimer's is more common in women than in men, as is often the case with autoimmune diseases.

There is even evidence that the virus herpes simplex, the same virus that causes cold sores, is implicated, which would open a whole new field of research.

Slip Sliding Away

The main challenge in diagnosing and treating Alzheimer's seems to be timing. The people who've just begun to show symptoms have been having Alzheimer's destroy their brains for 20 years or more.

"We've been starting too late," Sperling said, "because the disease evolves over decades and often has a threshold effect."

People compensate for the diminished capacity until they can compensate no longer, and we "don't try treatments until past that stage, when there already has been very significant damage to neurons." Meanwhile, the amyloid plaques have been growing, particularly in the forepart of the brain, she said.

For a while, researchers were flummoxed by the fact that 40 percent of older people autopsied had the telltale plaques and tangles in their brain but no symptoms of Alzheimer's, leading some scientists to think the cause and effect were backwards — the tangles are the result of a disease, not the cause. It is believed that if those people had lived longer they would have shown the symptoms.

What would help would be tests to detect Alzheimer's before the symptoms show, and that is at the core of massive amounts of research. Until recently, the only sure diagnosis was from an autopsy, of no use to the patient.

Testing for Alzheimer's

As it stands now, people who develop memory and cognition problems are given long tests, some lasting hours. The tests can be psychologically brutal. Patients suddenly are confronted with the basic things they can no longer do, like simple arithmetic, remembering words or names, or reproducing simple drawings. All the activities that they never realized they had lost the ability to do amidst the hustle and bustle of daily living are now staring them in the face.

Alzheimer's patients have a pattern of cognition loss that can be distinguished in the tests. When neurologists see the pattern, they assume Alzheimer's after they have eliminated all other physical possibilities. They have gotten good at it; they are almost always right. But the symptoms must be present for the test to be of any use, and by that time the patient has been living with the disease for 10 or even 20 years.

Clearly finding a test that could detect Alzheimer's before plaque begins to snake through the brain, and a treatment that would prevent cognitive loss would be ideal. Even one that stops the damage once it has started would be a good start.

So far that hasn't happened for a variety of reasons.

This is the second story in a multi-part series about the current state of research into and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. You can read part one here. Part three is available here.