3 Share Nobel Prize For Neuroscience Discoveries

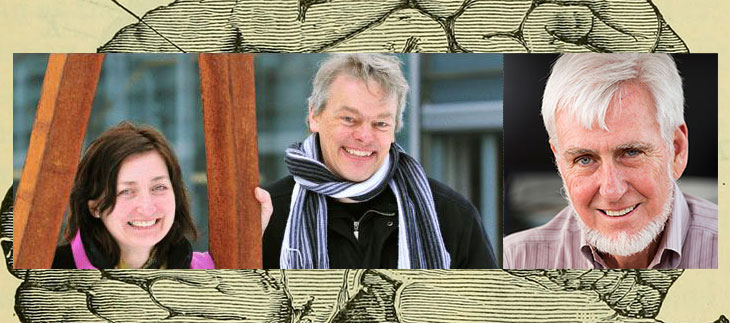

Winners of the 2014 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

Edvard and May-Britt Moser via Wikimedia and John O'Keefe via David Bishop, UCL. Composite image by Laleña Lancaster

(Inside Science) -- The 2014 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine has been awarded to a British-American neuroscientist and two Norwegian neuroscientists "for their discoveries of cells that constitute a positioning system in the brain."

The prize goes jointly to John O'Keefe, from University College London, and to May-Britt Moser and Edvard I. Moser, both from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, in Trondheim, Norway. The prize celebrates research that, for O'Keefe, first took place in 1971, and for the two Mosers, happened in 2005. The findings helped identify the way the brain creates a map of the area around an animal, and how animals use that information to navigate.

The Mosers are the fifth married couple to win a Nobel Prize, a line going back to Marie Sklodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre in 1903.

Their work explains how London cabdrivers can find intersections, why Alzheimer’s patients lose their way, and how we can walk home. They explain how we have a sense of place.

The discoveries can best be explained with the inevitable metaphor of the GPS system in an automobile. In the car, signals from space satellites position the car on the highway overlaying an onboard map. As the car moves, a computer in the car, knowing the position, tracks it along the map. The Nobel scientists found a similar system in two parts of mammalian brains.

The work was done with laboratory rats.

For more than half a century cognitive scientists have believed animals build a cognitive map of their environment and how to navigate through it, but had no idea where and how the brain did the computation. By the late 1950s, scientists developed the technology using tiny wires, to monitor the activity of brain cells.

A decade later, O’Keefe, working in a laboratory at University College London discovered one of the explanations -- place cells.

He found that as rats moved around in a large free-roaming area, cells in the back part of the hippocampus fired off. Individual cells fired off only when the animal was in a certain place, which he called the place field. There was a cell for each place, and the combination of cells and a combination of places, produced a mental map, retained by the rat, a gestalt of its environment. The rat knew where it was, its place in the world.

The rat did not have to relearn its place as it moved around, he found. It could rely on its previous experience -- it had been there before and remembered it.

The Mosers found it was more complex -- and remarkable -- than that. While the place cells in the hippocampus explained place, they did not explain navigation. The map in the GPS was too simple.

In 2005, they discovered that cells in another part of the brain called the entorhinal cortex fired off in a pattern by creating a hexagonal grid, something like a beehive pattern. When the animal reaches a certain location on the grid, a single cell fires and the animal knows where it is, just as a GPS system knows where it is on the map. A complex pattern of these grid cells produces the map.

The grid and place cells, along with cells that detect head direction, and border cells, which keep track of things like walls, tell the animal where it is and how to go from one place to another.

Humans have a similar system.

Other animals such as bats can navigate, suggesting that the system is the product of evolution.

Place cells can not only tell where we are but where we have been and where we are going. All that information is retained in memory. The memory is organized and consolidated as we sleep, scientists believe.

There are practical aspects to this research although it doesn’t offer any immediate cures to anything.

London cab drivers must pass a famous test before getting a taxi license. They must memorize London's entire street grid. Ten years ago researchers found the cabbies had much larger hippocampi than members of a control group.

More seriously, victims of Alzheimer’s disease eventually get lost. They are confused about where they are and how to get where they want to go. The disease may be interfering with the process O’Keefe and the Mosers discovered.

Joshua Jacobs, an assistant professor at the School of Biomedical Engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, said no one in his field is surprised at the winners, although it is a science the Nobel committee has not paid much attention to in the past.

“I think it is important,” he said. “I’ve devoted my life to it.”

Elizabeth Buffalo, an associate professor of physiology and biophysics at the University of Washington in Seattle, said the research could lead to important work in the future.

“The research provides us with the foundation of how memories are organized," she said. "The biggest areas of the brains involved are the areas involved in diseases like Alzheimer’s. If we better understand what happens there we can better understand what happens when it becomes diseased.”

O’Keefe was born in the U.S. in 1939, got his doctorate at McGill University in Canada and did post-doctoral work at London. He remained there and has dual U.S.-British citizenship. He is professor of cognitive science and director of the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre in Neural Circuits and Behavior at University College London.

“I have to say that at the beginning most people were quite skeptical at the idea that you could go deep inside the brain and find things which corresponded to aspects of the environment,” O’Keefe told Nobel Media. “I think it's taken a while, but … now the field has blossomed.”

The Mosers are both Norwegian citizens. May-Britt Moser, 51, and Edvard, 52, met at the University of Oslo. She studied at the University of Edinburgh, and is now professor of neuroscience and director of the Centre for Neural Computation in Trondheim, Norway.

May-Britt Moser was in meetings when she received the call from the Nobel committee. "I was in shock and I'm still in shock. This is so great," she told Nobel Media.

Edvard Moser also studied at Edinburgh and worked in O’Keefe’s lab in London. He currently is director of the Kavli Institute for Systems Neuroscience in Trondheim.

Edvard was in the air, flying to Munich when the prize was announced. He was a bit bewildered when personnel from the airport greeted him with flowers. "I didn't understand anything, and then finally I found out because I saw there were 150 emails and 75 text messages that had come in the last two hours," he said, also in a Nobel Media interview.