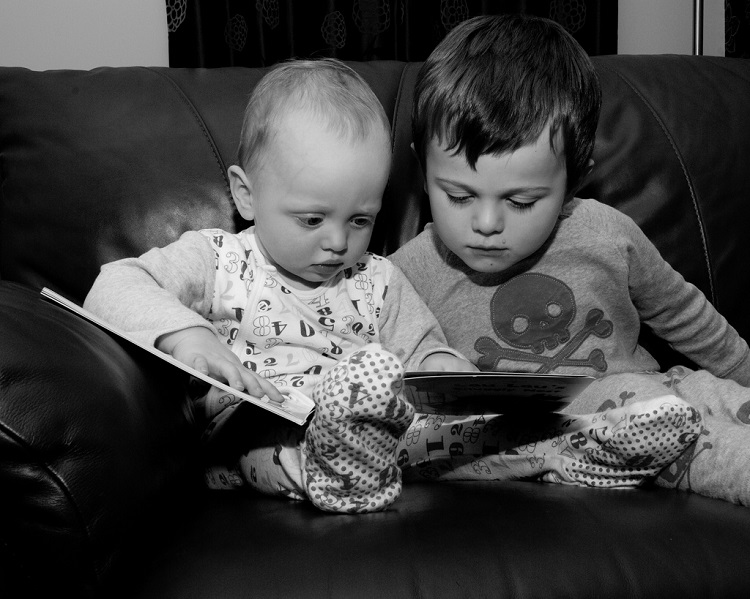

How Does A Young Brain Read?

DarrelBirkett via Flickr | https://www.flickr.com/photos/34459996@N04/5579865025/

By: Chris Cesare, Contributor

(Inside Science Currents Blog) – Cozying up with a good book can transport a reader anywhere, from Victorian England to the desolate craggy plains of Mordor. We take for granted how seamlessly our mind's eye paints these elaborate pictures, but it's natural to wonder how our brains learn to associate a word like "horse" with the image of a real horse and how important that association is while learning to read.

Neuroscientists are curious about that, too. They thought that understanding concrete nouns like "butterfly" or "fork" involved forging image, word and meaning in the brain. New research has shown that the situation might not be so clear-cut. Researchers found that children – even those who could understand words and match them to pictures – activate different networks of neurons than adults when they read.

"It's particularly surprising because these networks are thought to play a massive role in our understanding of the world," said Tessa Dekker, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London in the United Kingdom and lead author of the new study.

For more than a decade, neuroscientists have known about a striking connection between images and the in-brain responses they evoke. For instance, looking at a picture of a hammer activates motor neurons in the brain responsible for grasping, providing evidence for how the brain stores the idea of a hammer. Reading the word "hammer" also activates these areas in adults. Dekker and her colleagues assumed the same would hold true for children who understood the word "hammer."

To test this hypothesis, they designed an experiment to measure the brain activity of adults and children while they looked at stylized pictures and their corresponding words. The researchers chose 20 different tools and animals to display, with two different examples of each — two different images of cats, for instance, and two different fonts and colors for the word "cat."

First, the team verified that all the subjects could match the words to their pictures and read the words aloud. Then, they used an MRI machine to scan the subjects' brains while they looked at images and words for about two seconds each. They asked the subjects to press a button each time they saw the same picture or word two times in a row.

"The button-pushing made sure that the children weren't zoning out," Dekker said.

Every participant performed well on the task, and their brains responded similarly when they saw animal and tool images. But only in adults did the brain areas associated with the pictures activate when viewing the corresponding word. The children had not yet formed the connected network of motor, sensory and language centers scientists had thought was integral to reading comprehension, the team reported in the December 2014 issue of Brain and Language.

Given that the children could read, it's not clear what kids miss out on without these simultaneous firings, Dekker said.

Still, the study is an intriguing first step toward understanding the brain development of young readers, said Jessica Church-Lang, a neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the new study. It seems that the development of the brain regions involved in reading is not fixed even in proficient young readers, she explained.

"They don't hit some kind of plateau really early on — there's continued refinement going on as they become more and more exposed to print material," she said.

Dekker would like to do the same study with older children to search for the emergence of adult-like brain activity.

"It's a new way to tap into how children make sense of the words that they're reading," she said, adding that it's even interesting to think "that children might experience the words they're reading differently than we do."

Chris Cesare is a science writer based in Santa Cruz, California. He tweets at @chriscesare.