When Death Struck at the American Legion

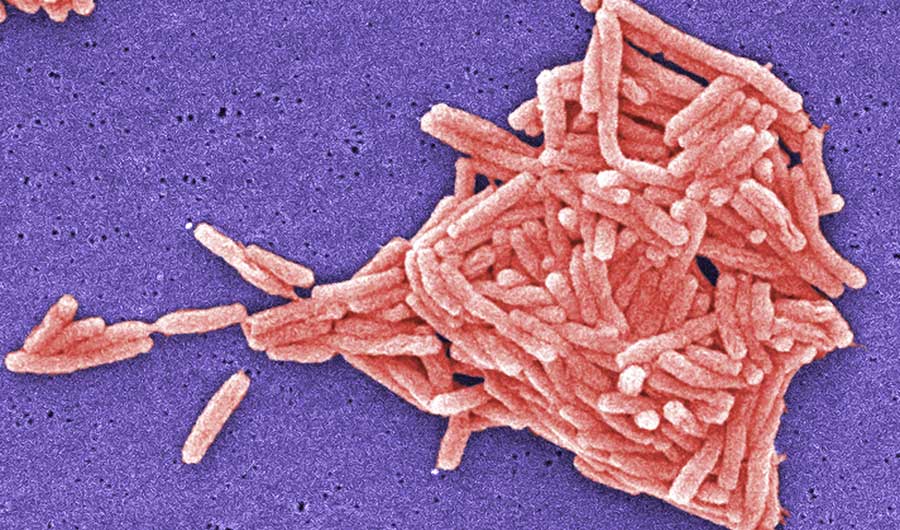

Colorized and magnified image of Legionella pneumophila bacteria

CDC/ Margaret Williams, PhD; Claressa Lucas, PhD;Tatiana Travis, BS

(Inside Science) -- In July 1976, 4,000 World War II veterans, members of the American Legion and their families, met at Philadelphia's Bellevue-Stratford hotel for the annual convention of the Pennsylvania American Legion.

The convention came at a tense time in America. It was just days after America’s bicentennial celebration and only a few blocks from the place where the Declaration of Independence had been debated and signed 200 years earlier. But the country was living in fear. Scientists had warned of a potentially catastrophic outbreak of swine flu, and the administration of President Gerald Ford was attempting to get all Americans vaccinated before it struck.

Horrible images of the great influenza epidemic of 1918, which killed between 20 and 40 million people worldwide, had received considerable attention in the media. So, when the veteran warriors who attended the American Legion convention began getting sick and in some cases dying from an unknown disease, attention locked in on Philadelphia. It took more than six months to find the cause -- which was announced 40 years ago this week, on January 18, 1977.

It was a scientific challenge for science and journalism, and put a then little-known federal agency on the front pages.

The hotel, a gem of Philadelphia’s downtown area, Center City, was built in 1907 two blocks from the city’s rococo City Hall topped by its iconic statue of William Penn, the city’s founding father. The restaurant on the first floor was the meeting place of Philadelphia’s political elite. It was once one of the great hotels of the world; the interior in 1976 was elegant, if faded -- and air-conditioned.

When the convention ended July 24, the men scattered to their homes around the state. Several days later, many of them became ill. Some were so sick they were hospitalized, and one man registered a temperature of just over 107 before he was covered in a cooling blanket. Then some began to die.

The summer they fell

Ray Brennan, 61, a former Air Force officer, one of the first, died at his home, apparently from a heart attack. Frank Aveni, 60, also appeared to have a heart attack and died. Both men complained of feeling tired, congested and fevered. Both reported chest pains. They seemed to have some of the symptoms of the flu, just what people had feared.

Six more died within 24 hours.

The first hint something weird was going on came from a small-town physician, Ernest Campbell, in Bloomsburg, in eastern Pennsylvania, who treated three men, all sick with the same symptoms. He noted the three had all been at the convention. He called the state Department of Health. On August 2, a Veterans Administration physician in Philadelphia called what is now called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in Atlanta, to report four deaths from pneumonia from people who had been at the convention.

The CDC, an agency most people had then never heard of, sent 20 investigators, the largest number they had ever deployed.

The hunt began to find the cause, with CDC epidemiologists interviewing everyone they could find who was at the convention about everything they did, what they ate and where, and where they went.

Several oddities became apparent. Whatever it was, it did not behave like the flu. It was not contagious. In one instance, several men drove to and from Philadelphia in the same car, but only one became ill. Had it been a flu virus most likely some of the others would have become ill as well. No family members or health workers contracted it, but some people who had simply walked in front of the hotel were infected.

Something wicked lurked at the Bellevue-Stratford and no place else in the city. The hotel closed.

Finding the cause

There were three possible reasons for the outbreak: an accidental poisoning with some chemical toxin, like a metal in the air; a deliberate act of terror; or infection with a previously unknown pathogen. The first two were ruled out quickly. That left a virus or a bacterium.

“I did think it was a virus and I certainly wasn’t alone with the thought,” said Harvey Friedman, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, then running the clinical virology laboratory at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “We are more used to viruses being epidemic. They spread by person-to-person contact.”

“If a virus was the right answer I was in position to find what this thing was. It was pretty exciting.”

He kept coming up empty handed.

Months went by and despite all the efforts of the CDC, no answers were found. Tensions rose. The story stayed in the media, concentrating on the fact the experts had no answers. The disease appeared to lead to a form of pneumonia, but what was it? The newspapers were publishing body counts and covering funerals.

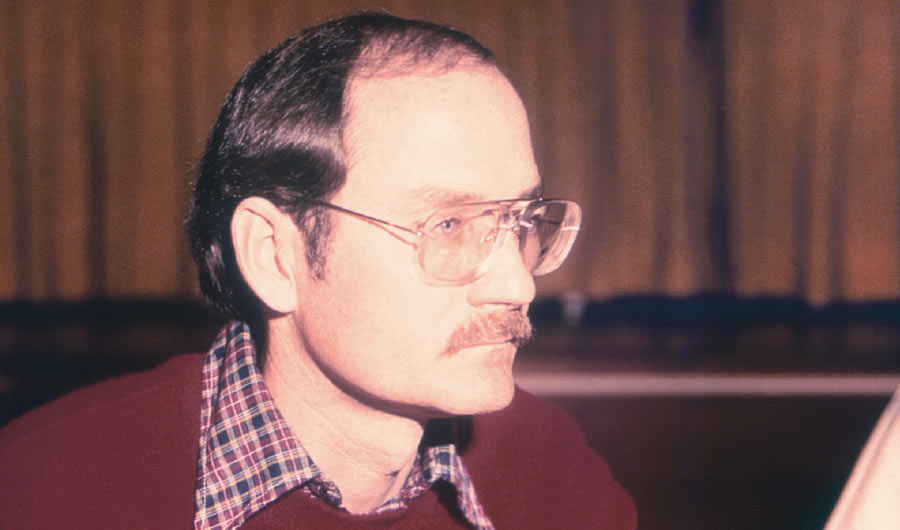

In Atlanta, a CDC microbiologist who called himself a “backbencher,” Joseph McDade, began running tests on tissues from victim autopsies in his lab but all he could do was contribute to a “mountain of negative results.”

At a Christmas party, someone who knew McDade worked at the CDC accosted him. McDade still does not know his name, but the man told McDade he was disappointed in the experts -- that people were dying and they could not find out why.

McDade was upset. Several days later, during the holiday break, he went back to his lab to do miscellaneous chores he usually saved for that time, and decided to look at his microscopic slides once more.

He had noticed in earlier investigations a few rod-shaped bacteria in the samples, that had been taken from patients and subsequently grown in guinea pig tissue and eggs. They had seemed to him initially to be just normal detritus from human lungs. He ran another test, this time minus the disinfectant he had used previously.

“What I saw was one microscopic field teaming with bacteria,” McDade (who no longer does media interviews and declined to comment for this story) told a conference at the CDC. Further testing proved the bacteria was the cause of the outbreak and was not really new. Cases of infection by the same bacteria went back to the early 1940s, and scientists at the Walter Reed Army Hospital had isolated it in 1947. McDade named it Legionella.

The bacteria was traced back to the Bellevue-Stratford air conditioning system’s cooling towers, and the 18,000 cases annually requiring hospitalization today in the U.S. come from similar environments.

The final death toll from the Philadelphia outbreak was 34 dead out of 221 cases. While it remains a serious infection, today doctors know to look for it and it is typically treated successfully with antibiotics, Friedman said.

McDade is now retired as scientist in residence at Berry College near Rome, Georgia.

The hotel, now part office, is open again for business.

The disease still pops up in small outbreaks, including in 2015 at a converted opera house in the Bronx in New York City. Eleven died in Portugal in 2014. In 2016 there were cases in Minnesota, Tennessee, and Washington State among other places, including a pool and spa in Long Island, N.Y.

The death rate is about 10 percent.

A milder form of the disease is called Pontiac fever.