Scientists Release First Photo of a Black Hole

An artist's rendering of the black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy.

Copyright American Institute of Physics (reprinting information)

(Inside Science) -- The first-ever photograph of a black hole looks something like a cosmic wedding ring. Bright light encircles the void of a supermassive black hole billions of times the mass of our sun, which lurks at the center of an elliptical galaxy located 55 million light-years from Earth, known as Messier 87.

"We have now seen what we thought was unseeable," said Sheperd Doeleman, a Harvard astrophysicist who is the director for the Event Horizon Telescope project, a global collaboration to observe the immediate vicinity of what he called the most mysterious objects in the universe. Doeleman spoke in Washington D.C. at a press conference unveiling the photograph today.

"One of the great privileges of being a scientist is we get to see something new first," said Avery Broderick, an astrophysicist at the Perimeter Institute and the University of Waterloo in Canada. "Our eyes are the first to see an image of a black hole or discover a new physical process, or some way in which the universe has unfolded itself. And then we have the privilege of sharing it."

Today, a team of researchers unveiled the above image of a black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, 55 million light years from Earth.

Credit: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration

Although scientists have studied black holes for decades, they had never actually seen one until now. They constructed this first-ever image by observing light in the radio wave part of the spectrum that had just barely escaped the black hole's clutches. The light was born millions of years ago in the violent neighborhood surrounding the M87 black hole, where superheated gas whips around at near light speeds. The light ring glows more brightly on the bottom half of the image because this material is being flung toward Earth. In the center, the black hole has cast a silhouette by severely contorting the very space-time that the light travels through.

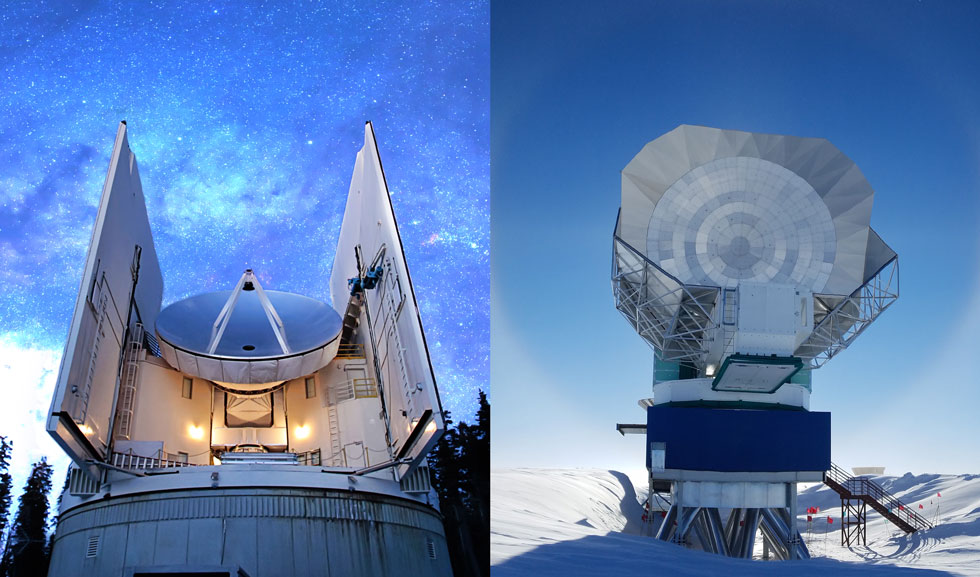

To take the picture, scientists braved some of the most extreme environments on Earth, from the thin-aired, high Atacama Desert in Chile to the subzero icebox of Antarctica. They gathered data using 8 far-flung radio telescopes to create an image with the same resolution as if it had been taken by one gigantic Earth-sized telescope -- 1,000 times more fine-grained than any space picture taken before.

The effort combined "the most advanced electronics, with a planetary-scale collaboration, with the most advanced statistics, with new imaging techniques," said Peter Galison, a science historian from Harvard who spoke about the symbolic meaning of the EHT project as part of a panel discussion held at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas in March.

The Submillimeter Telescope in Arizona (L) and the South Pole Telescope in Antarctica (R) two of the telescopes in the eight-telescope Event Horizon Telescope Array.

Credit: David Harvey (L) and Junhan Kim, The University of Arizona (R)

The scientists collected the data that went into making the image -- so much that it had to be stored on a half a ton of hard drives -- in the spring of 2017, and spent close to two years calibrating, analyzing, checking, and re-checking it. They released the image this morning to reporters and the public and have published several scientific papers describing the findings.

"When I saw the picture, I was thrilled by it," said Roger Blandford, a black hole expert at Stanford University who was not directly involved in the project.

Initial measurements of the black hole's shadow suggest that the theory of general relativity -- Einstein's explanation of gravity -- holds true even in the most extreme conditions.

More stories from Inside Science about black holes

Every Black Hole Contains a New Universe

Black Hole Cores May Not Be Infinitely Dense

A black hole is like a stage, said Blandford, and the new observations seem to confirm that Einstein was right about how it is set up.

But a second part of black hole investigations is about watching the scenes that unfold on this stage, Blandford said. "The play is what happens to the gas around it. It's like predicting the weather; it's hard."

In that sense, the first-ever photo of a black hole is more of a beginning than an end point, he said.

For example, the initial data gathered in 2017 covered a time span of about a week, but it would be possible to watch how the M87 black hole changes over the course of months or years, Broderick said.

"Now we are prepared to move on from black hole portraiture to black hole cinema," he said.