Japanese Balloon Attack Almost Interrupted Building First Atomic Bombs

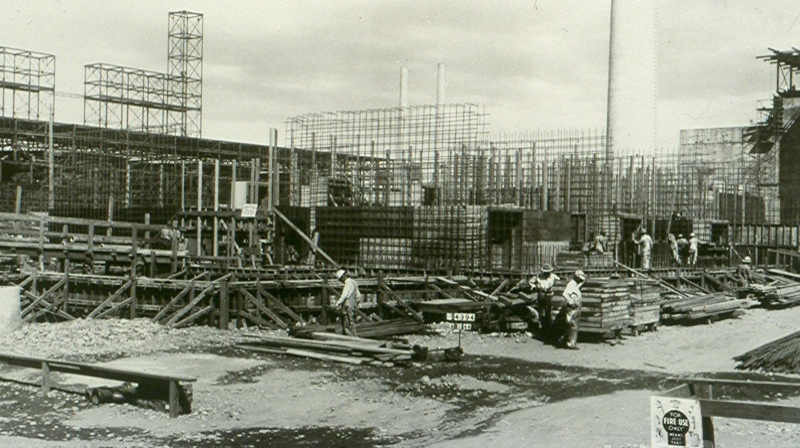

Reactor B at the Hanford site in Washington state, under construction in 1944.

U.S. Department of Energy, http://www.hanford.gov/c.cfm/photogallery/gal.cfm/BReactor/#

(Inside Science) -- On March 10, 1945, five months before World War II ended in mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese accidentally came close to ending production of the radioactive materials needed for the atomic bombs -- using paper balloons.

One of the thousands of bomb-carrying balloons they launched into the jet stream toward North America knocked out electricity for a moment to the plutonium processing plant in Hanford, Washington. Had it not been for conservative engineering, the attack might have succeeded in stopping production.

Only a small percent of the balloons reached land, but six people, five of them children, were killed by one balloon that landed in Oregon.

“They were incendiary devices,” said Charles Clark, adjunct professor and co-director of the Joint Quantum Institute at the University of Maryland, College Park, a native of Washington state. The hope was at least to start forest fires and trigger panic, he told an audience at a meeting of the American Physical Society in Baltimore on Wednesday.

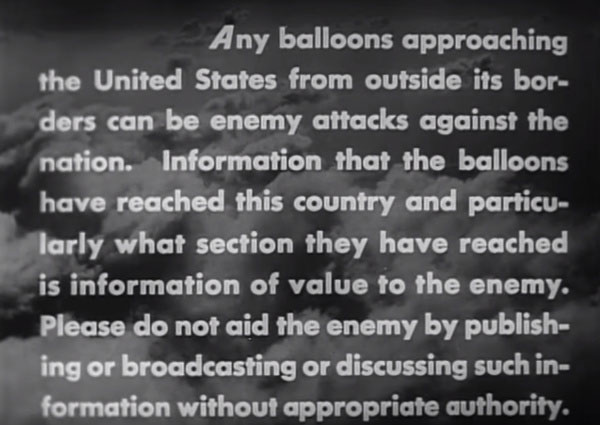

The overall effects turned out to be minimal. The balloons generally were launched during the winter months to take advantage of a strong jet stream, but the forested mountains of the American West were snow covered and unlikely to ignite. Moreover, the attacks were kept from the media to prevent panic so most Americans didn't know about them. The government censorship office, which had authority over wartime news, forbade publication.

Hanford was crucial to the Manhattan Project, because it produced the plutonium needed for the U.S. bombs. It had been created as an adjunct to the Chicago laboratory built for Enrico Fermi, who produced the first chain reaction.

Located in the high plains of central Washington at the junction of the Columbia and Snake Rivers, the area was sparsely populated and known mostly for vineyards and apple and cherry orchards, Clark said.

It was chosen partly because of its remoteness and partly because the rivers never froze in the winter. A thousand tubes of uranium were inserted in the reactor to produce plutonium, and water was needed to cool the reactors.

Built in 18 months, the huge facility eventually employed at least 40,000 people, making it the fourth or fifth largest city in Washington. Virtually none of them knew what they were working on until after the Hiroshima attack when they read about it in the local newspaper.

The Japanese plan was audacious.

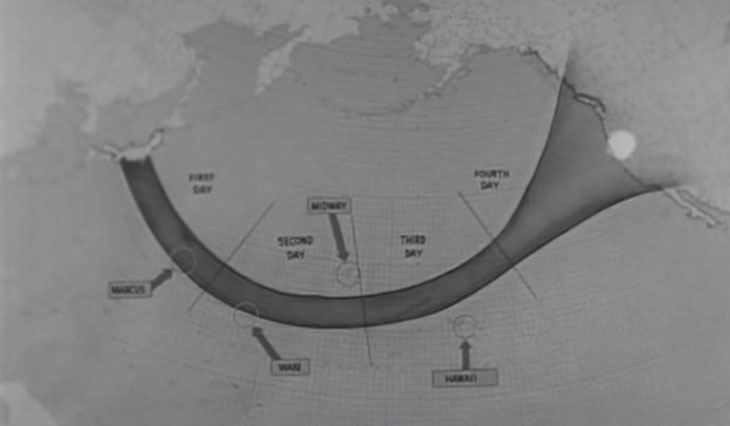

“The Japanese, with their characteristic sense of style, invented some balloons -- some 30 feet in diameter -- made out of paper from mulberry trees and they attached a bomb,” Clark said. A simple timing switch triggered the bomb after three days.

It is believed the Japanese launched more than 9,000 hydrogen-filled balloons, starting Nov. 3, 1944, of which only a small percentage actually made it to land. About 300 bombs were detected, but most landed in remote areas, and as late as 2014 unexploded bombs were being found in western Canada.

The U.S. and Royal Canadian Air Forces shot down several before they exploded, but balloons made it to California, the Canadian Yukon, and as far east as Detroit, where it set fire to a garage, Clark said.

On Feb. 1, 1945, a balloon was spotted by local resident over the Trinity National Forest in Northern California near the town of Hayfork. It landed on a dead fir tree near a road. A crowd gathered to see it and shortly after sundown, it exploded. No one was hurt. The gasbag disappeared, and the undercarriage, including four incendiary bombs and one high explosive, fell to the ground. It was one of the few balloon payloads recovered.

On May 5, 1945, a pregnant woman, Elsie Winters Mitchell, and five children were killed by a bomb near Gearhart Mountain in southern Oregon, the only known civilian deaths in the continental United States in the war.

What happened at Hanford was a fluke, Clark said. One of the balloons draped over the main electric transmission line from the Grand Coulee dam and the Bonneville dam on the Columbia River, causing a short circuit and shutting down the Hanford cooling plant. The Japanese had no idea what was going on at the plant if they even knew it existed, according to Clark.

It happened just as Hanford was producing the plutonium that would be used for the Trinity bomb test in New Mexico and the bomb that destroyed Nagasaki.

The engineers who built the plant, and the DuPont company running the facility, had constructed several backups, including a coal-fired generator that kicked in as soon as the power went down, and the processing continued uninterrupted. The power was off for one-fifth of a second, according to Col. Franklin Matthiass, the engineer in charge of the facility.

The operators had also set up an emergency system designed to drop emergency rods into the reactor to shut it down, but it was not triggered by the balloon attack.

“We never had the guts enough to test that,” Matthiass said in an interview published on the Atomic Heritage Foundation website. The scientists had warned that even the slightest interruption in the cooling system could lead to an explosion of radioactive material, but they weren’t sure. The balloon at Hanford never exploded; it just shorted out.

Had the backup not been there, it would have been “fire city” at the reactor site, Clark said.

Now decommissioned, the Hanford site is one of the largest nuclear waste facilities in the world and a major Superfund site, containing large amounts of liquid and solid radioactive waste, in addition to contaminated groundwater.

Editor's note: The photos used in the body of this story are part of a U.S. Navy training film from World War II, which is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGWvyhYActc