To Stone The Devil, Safely

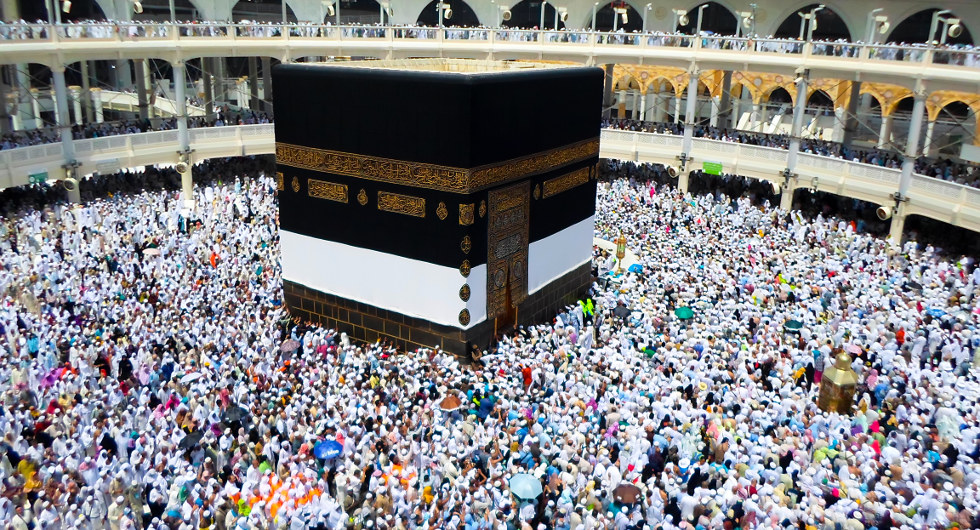

In the Saudi holy city of Mecca, pilgrims circle the Kaaba in the Grand Mosque.

(Inside Science) -- In 2015 the world witnessed the danger of losing control of a crowd when a deadly stampede occurred during the hajj, a massive pilgrimage that brings millions of Muslims to Mecca, Saudi Arabia every year during the last month of the Islamic calendar.

Last year’s disaster happened on the outskirts of the holy city. The pilgrims were making their way to the Jamarat Bridge for an important ritual of the pilgrimage known as the "stoning of the devil." According to the Associated Press, as many as 2,411 were killed, but the Saudi government's public statements claim that 769 people perished.

The actual number of deaths is just one of the many questions that remains unanswered about the tragedy, the largest of which is what caused the stampede in the first place. Systems researchers and security companies are reluctant to talk on the record about who or what may be responsible, and there has been no official, public report from the Saudi government about the details of the disaster.

However, crowd management experts have pieced together educated guesses about what may have caused the deadly crush. It's a frustrating task, said Amer Shalaby, a civil engineer at the University of Toronto, who studies large-scale events such as the hajj.

"You can explain around it, but you can't exactly put your finger on exactly what happened," he said. The cause may not be the result of one single thing, he added. Instead, a number of different factors may have tragically coalesced to cause the disaster.

In conversations with scientists who study crowd control and other experts on the region, Inside Science has learned that last year a new company took over the responsibility of scheduling the crowd's movements in the area where the stampede took place. In addition, experts and pilgrims' groups have questioned whether the travelers were sufficiently prepared, whether the crowd enforcers on the ground were strict enough, and whether the sheer size of the crowd means the risk of a stampede can never be eliminated.

This year, the hajj begins on Sept. 9. The Saudi government says improvements in safety have been made, but because there is still no publicly available documentation of what caused the deadly crush, it remains unclear what areas needed improvement, or what changes have been made to improve safety. That has some experts worried that another disaster could occur.

Protecting the crowd

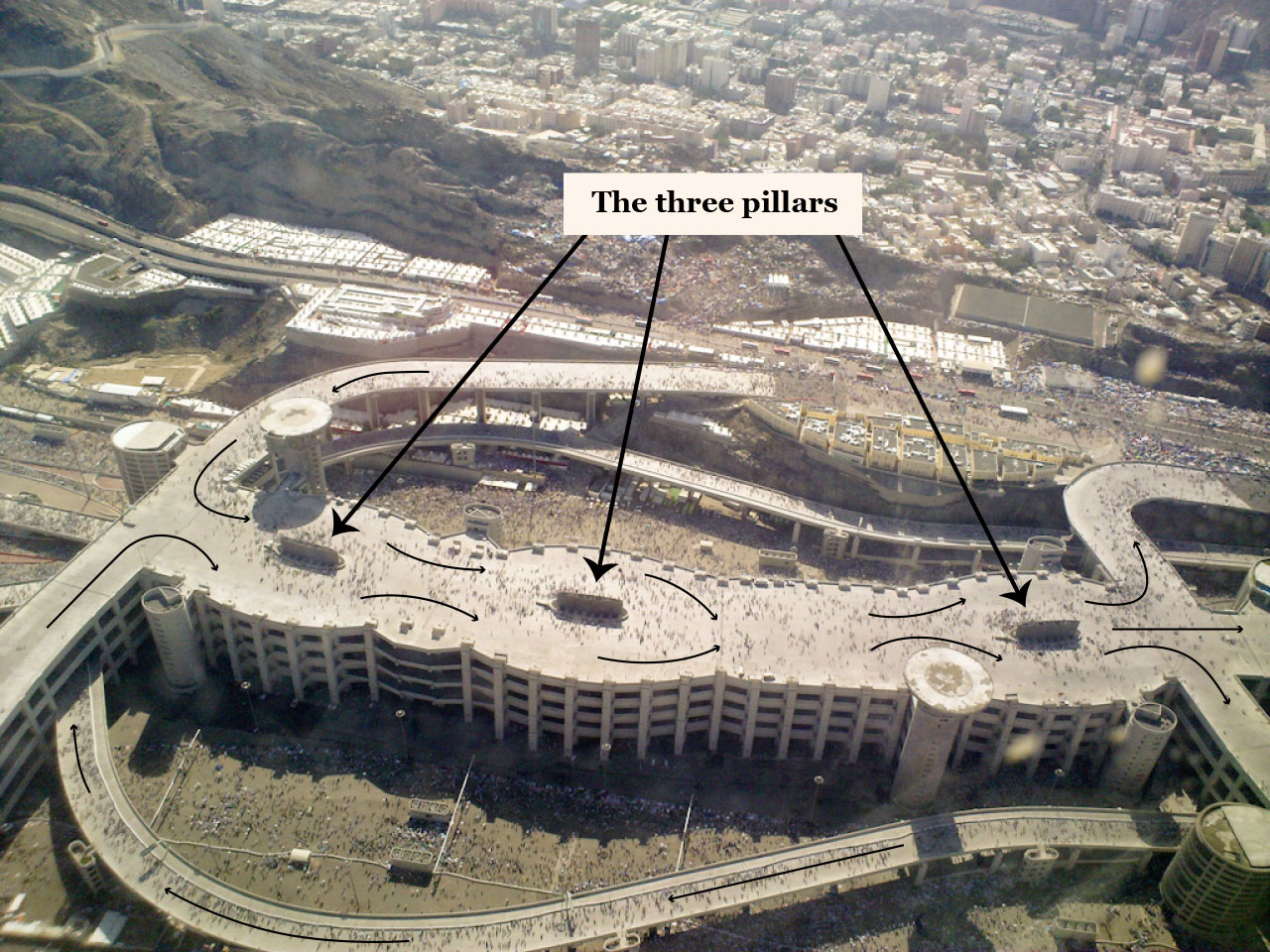

If you were one of the two million or more registered pilgrims who make their way to Mecca every year for the four to five days of the hajj, you would start at the Grand Mosque. With fellow pilgrims, you would circle a shrine in the middle of the mosque called the Kaaba seven times in a counter-clockwise direction. Later, you move on to the Mina neighborhood in Mecca before taking time to pray at the site of Muhammad's last sermon. At the next stop in an open space outside of Mecca called Muzdalifah, you would stop to collect pebbles to be used the next day when you return to Mina and make your way to the Jamarat Bridge, one of the main phases in the pilgrimage. There, on a multi-level conveyance built around three stone pillars you would throw the pebbles and pelt the pillars -- symbolizing the stoning of the devil. Finally, you would return to the Grand Mosque and circle the Kaaba seven more times.

Throughout this journey, you and the other pilgrims would be monitored and your movements controlled by what is thought by experts to be among the most advanced and sophisticated surveillance systems in the world involving cameras, human on-the-ground controllers, and a complicated set of mathematical calculations.

The cameras capture images that are processed to automatically count the number of pilgrims, offering real-time data on the flow of the crowds as they make their way from site to site. This real-time data is designed to act as an early warning system if the crowds become too dense anywhere.

The calculations are used to determine the best time for groups of pilgrims to approach the Jamarat Bridge. These equations also suggest the best route for a group to take from their camp to the bridge, creating a schedule. Human controllers on the ground enforce this schedule and guide traffic, pausing movement when necessary.

Published data from these cameras show that the crowds are sometimes larger than the number of people expected to be present. To go on the hajj, pilgrims must register with the Saudi government, which regulates the number of visas given to foreign nationals to keep numbers under control. But to complicate matters, as many as two million additional unregistered pilgrims, mainly domestic acolytes from Saudi Arabia, also perform the hajj each year. This can bring the total number of pilgrims in excess of four million.

Despite this sophisticated crowd management, the system is not flawless, which last year's stampede somberly demonstrated. It was the worst hajj disaster in decades. There have been a number of similar stampedes in the past, but none with a death toll as high as the figure reported by the AP.

Learning from mistakes

According to consultants who were contracted in the past to help prevent such disasters, in preparation for the hajj, a team of crowd management experts has spent many hours behind their computer screens, running simulations, planning exit routes, minimizing blockages and trying to predict and control the mass movements of the crowds.

But crowd management systems are improved by analyzing what went wrong, which helps experts to learn from mistakes, said Doug Samuelson, a crowd management expert and chief scientist at the logistics and information technology company, InfoLogix in Annandale, Virginia.

While the Saudi government says improvements have been made for 2016, they have given no official explanation of what caused 2015's deadly crush in the first place. So are the lessons learned from last year playing a part in the improvements? Administration for the hajj falls under the jurisdiction of the Saudi Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs. The ministry was contacted via email in both English and Arabic to request an interview. Phone calls were also made, but Inside Science received no replies.

Even with no public comment, Shalaby speculates the lessons may have been taken into account because while the government doesn't always foresee and forestall potential problems, they do embrace hindsight. "They tend to be reactive to the problems that have emerged in previous years," he said.

Moreover, the Saudis take safety on the hajj very seriously, Shalaby said.

"The Saudi government views itself as the custodian of the hajj," he said.

One example of the seriousness of official attention is the Jamarat Bridge itself. It was redesigned and rebuilt just a decade ago at a spare-no-expense cost of $1.1 billion to address safety concerns. Those earlier concerns followed another stampede in 2006 where an estimated 345 people died. The new multi-story pedestrian-only bridge is almost a kilometer long and wraps around three pillars, where the pilgrims cast their stones. Possibly the most expensive pedestrian bridge ever built, the crossing has 11 entrances and 12 exits, escalators and emergency escapes. It is designed to facilitate the passage of 480,000 people per hour.

"Even if you have more than two million people, it's still huge," recalled Dr. Hisham Burezq, a plastic surgeon from Kuwait who has taken part in five hajj pilgrimages. He last went in 2014, the year before the stampede. His experience on the bridge was generally smooth.

"There's a short period of shoulder-to-shoulder crowding, but it's not for more than a few minutes," he added, "It's very well organized." Burezq said he is not making the pilgrimage this year, but that he wasn't put off by safety concerns.

He also points out that things are tightly organized on the ground -- pilgrims are ushered around in groups with chaperones. "They have motorcycles that go on ahead in front of us to check there's no crowds," he said. "Then they'll call the rest of the group to say it's safe to move on."

Figuring out what went wrong

All of this organization and crowd control may reassure Burezq and other hajj goers, but it failed to stop the disaster in 2015.

Some experts point to the limitations of the system. "It seems to have worked well, if organizers stick to it," said Samuelson, "But they found out that if you let it slip, bad things happen," he continued.

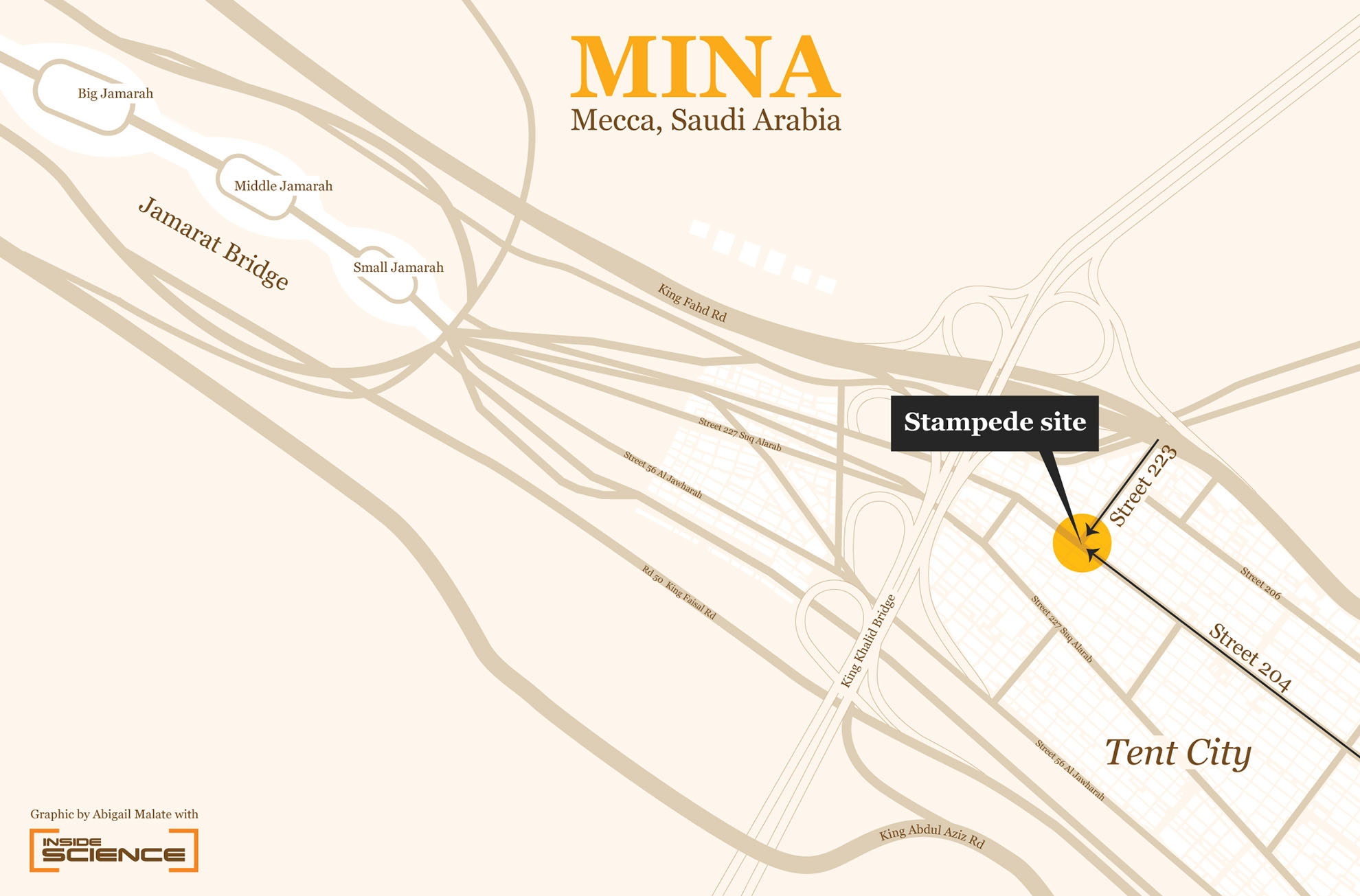

What seems clear is that the bridge itself and the roads leading up to it may still be a pinch point. According to multiple news reports, last year's accident happened when two large flows of people trying to reach the bridge descended on each other at right angles on a street corner in Mina.

Last year's stampede took place at an intersection in Mina as pilgrims were making their way to the Jamarat Bridge.

Abigail Malate

CC BY-ND 4.0

"There are too many potential intersections of crowd flows towards Al-Jamarat," wrote Keith Still, a professor of crowd science at Manchester Metropolitan University, in an email. Still was also a special advisor on crowd modeling from the Jamarat Bridge between 2000 and 2005.

Those who study the science of crowd movement often make comparisons to fluid dynamics. If you pack enough people into one space all with the aim to reach the same place, the mass of people flowing towards that destination ends up taking the path of least resistance. That means the crowd can be managed and controlled much like the flow of a liquid, unless something goes wrong and people panic.

Samuelson said the combination of the two crowds to create a bigger mass didn't by itself cause the panic and resulting stampede. The two groups heading in different directions converged at right angles, intersected and blocked each other’s flow. "That gets problematic very quickly," said Samuelson. "Panic can consist of moving a lot or just freezing."

Recent research explains crowd's vulnerability

While the surgeon Burezq said he has only ever experienced a few minutes of intense crowding, experience and crowd models show that it doesn't take long for overcrowding to cause significant problems. "When crowds exceed 4-5 people per square meter in moving situations, a jam can occur and pressure builds up very quickly," wrote Still.

But according to research published in the journal Interfaces in April, crowds near the bridge can be as compact as 10 people per square meter.

The paper outlined improvements -- such as the counting cameras that help monitor the crowd -- that the Saudi Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs made in the years prior to the 2015 disaster. The study authors, a coalition of two employees at the ministry and five German crowd science experts, helped to facilitate these improvements by finding the right experts to deliver them. But, as the paper points out, last year the coalition was "no longer in charge of the scheduling and routing recommendations for the stoning-of-the-devil ritual."

Just one of the authors, Dirk Helbing, was willing to answer questions on the record -- albeit only by email. Helbing is a professor of computational social sciences at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. Of the other six, four did not respond. The other two simply wrote that they were unable to share any information other than what was already published in the research paper. One of them, researcher Knut Haase, appeared to distance himself from the disaster in his reply by writing that they did not collaborate with the company in charge of scheduling when pilgrim groups made their way to the bridge last year.

"I would not want to be in charge (and have therefore decided not to be) because there are factors that are not sufficiently controllable," Helbing also wrote in another email.

"The planning and implementation process is complicated, so that things can potentially go wrong in different parts of the overall process," he added.

Samuelson said he didn't think there was anything wrong with the crowd management model itself, and he added that there didn't seem to be anything unique to 2015 compared to previous years. "There wasn't a suicide bomb or anything that spooked the crowd," he said, which left him wondering if the crowds are just too big to completely eliminate the risk of accidents.

New company controlled the pilgrim schedule in 2015

Last year, the Saudi government changed the company in charge of scheduling when the pilgrim groups can approach the bridge. The contract was awarded for the first time to a management consulting company called Sejel Technology, which is based in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Haithem Durrah, a spokesperson for the company, confirmed that it remains the organizer for the pilgrim schedule at this year's hajj. He also said it is in charge of managing the pilgrims' applications and data.

At this year's hajj, Durrah said, new innovations will be deployed. "The ministry is working on distribution electronic bracelets to pilgrims to follow up with them and monitor their movement, which should be very helpful," he said.

Concerning last year's stampede, he said, "There were irregular groups, who rushed in at the wrong time during the annual hajj pilgrimage in Mina, Mecca. This year, more restrictions will be implemented to avoid these groups."

When asked if he thought Sejel Technology bore any responsibility for the stampede, he denied it. "Not at all. We are not responsible," he said.

When asked the same question, Helbing said he did not want to engage in scapegoating and declined to comment further.

Shalaby was slightly more forthright about the company. "It could possibly be a contributing factor," he said.

There are multiple stages involved in rolling out a new safety measure, explained Helbing. First, international experts make recommendations; secondly, a team of Saudi experts decides which of those recommendations are to be used. "They may also decide to deviate from the international experts’ recommendations," wrote Helbing. Finally, the Saudi government awards contracts to organizations that then deploy and manage the recommendations.

Perhaps not all safety measures and critical information on how to properly use the crowd management systems were passed on to the contractors, said Samuelson.

"It's possible that the technology transfer wasn't complete," he said. "The job isn't done until you've taught the people who are going to be running the system."

Helbing said he and the other authors were investigating last year's accident but declined to reveal any findings. However, he wrote, there are too many variables for organizers to control all of them.

Are hajj crowds too big to completely prevent accidents?

Every year, the hajj is the largest gathering of human beings on the planet. Although the pilgrims are all Muslims, many may not speak Arabic or English, which adds to the complexity of managing millions of people when orders need to be issued.

The challenge of keeping such large crowds safe is why pilgrim welfare organizations such as the Association of British Hujjaj advocate for Hajj goers to be better educated in health and safety concerns before they leave for the pilgrimage.

It's the biggest gathering on the face of the Earth. -- Farhan Khalid

"The lack of education prior to going is a contributing factor to what happened in 2015," said the organization's spokesperson Farhan Khalid. "It's the biggest gathering on the face of the Earth," he said, "But when people go, they don't take the health and safety concerns to heart."

Khalid explained that many pilgrims don't take enough water or sun umbrellas despite having to walk for long periods of time in temperatures exceeding 100 degrees Fahrenheit. He partly attributes last year's tragedy to this lack of basic protection from the oppressive heat. "People were so weak and dehydrated at the time [of the stampede] so if one person fell they were too weak to get back up," he said.

His organization is calling on the Saudi government to make public their internal reports about the 2015 disaster. "We'd like to see the report published so people can learn lessons. Otherwise what's the point?" he asked, "It's not just for the Saudis to learn lessons but also the people that are going on hajj."

In May, Iran announced its intent to boycott this year's hajj by not sending pilgrims. In a flurry of very public and targeted insults, the Iranian government has accused Saudi Arabia of failing to make sufficient safety guarantees and of being unwilling to accept some of their security requests. "Considering the continuation of Saudi Arabia's obstructive moves, Iranian pilgrims will be deprived of Hajj this year and its responsibility falls with the Saudi government," said Iran’s Hajj Association in a statement.

According to Ross Harrison, a Georgetown University professor and an expert in Saudi-Iranian relations, the two countries are locked in a Middle Eastern regional "cold war," which is fought on many fronts — one them through propaganda. This makes Tehran’s criticisms of Saudi Arabia’s safety measures politically tainted, he said.

Meanwhile, less publicly, some crowd managers and scientists worry that the possibility of a reoccurrence at this year's hajj is not diminished.

"The risks may remain as problems lying in wait," wrote Still. In many other countries, “there would be an enquiry and information would be published for review," he continued.

Reasons for hope

As for the Saudis, Samuelson said that they have made substantial safety investments in the past and commissioned various studies to identify safety risks. The hajj and the security of those taking part are supremely important to the Saudi government, he said. While something in the crowd management system or its operation may have gone wrong or some other, unknown factors may have led to the 2015 tragedy, it was an exceptional event. Ensuring the safety of millions of pilgrims is a gargantuan and complicated task for the government to undertake every year, and it's an achievement that most years pass without a major incident at the hajj, he said.

Indeed, Samuelson said this is the Saudi government's point of view. "The official position is that stuff happened, and we did our best and even in the best circumstances, you get an accident," he said.

Samuelson hopes that privately within the government the real cause of the stampede has been acknowledged, otherwise the risk of a 2015 repeat cannot be ruled out. "I hope to God that somebody in authority will say the fundamental error was X," he said.

Shalaby, for his part, thinks these sorts of conversations are exactly what have been going behind the scenes in government chambers since the stampede. "To give them some credit," he said, "they seem to tackle the problems and devote a lot of resources."

"I think there will be a tremendous effort to avoid this from happening again," he added.

Rasha Faek contributed additional reporting for this story.