Will Hurricane Harvey Launch a New Kind of Climate Lawsuit?

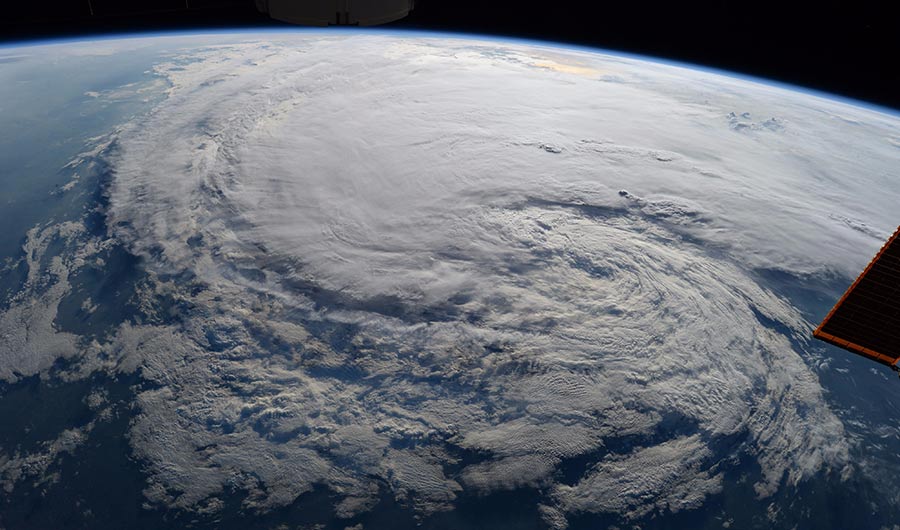

Picture taken from the International Space Station on August 28, 2017 of what was then Tropical Storm Harvey.

NASA/Randy Bresnik

(Inside Science) -- As Houston residents return home to devastation from Hurricane Harvey, Heidi Cullen is figuring out how much of the disaster was our fault.

According to common wisdom, what she's doing is impossible. Scientists have been saying for decades that you can't blame any specific weather event on climate change. But while Cullen and researchers like her still can't say for sure that a particular storm such as Hurricane Harvey or Irma was caused by climate change, they are getting good at determining how much humans have weighted the dice. Now, this field of "extreme event attribution" may be poised to make its debut in court.

"It's not good enough to say, 'You can't attribute an individual event to climate change,'" said Cullen. "We actually have the tools to do this."

In recent days, she has been fielding more and more calls from the legal community, Cullen added. She said she has never been a paid consultant for any legal issues.

Linking weather to climate change is possible

Cullen is chief scientist for Climate Central and leader of the World Weather Attribution program, an international collaboration that aims to analyze the role of climate change in extreme weather events soon after they happen. Her team uses mathematical models of Earth's climate to run simulations of particular weather events, such as the 50 inches of rain that Harvey dumped on parts of Houston last month. Then, they run the same models again, this time simulating an imaginary world where humans haven't released the greenhouse gases that drive climate change into the atmosphere.

By comparing how often weather events crop up with and without climate change, Cullen's team can estimate the degree to which humans contributed to an event's likelihood or severity. For example, when her team analyzed the deadly heat wave that struck Europe this past June, they found that climate change increased the chances of such extreme temperatures in Spain and Portugal by at least a factor of 10.

"When you get to numbers that are that large, it really shows how much risk has increased as a result of burning fossil fuels," she said. Cullen has no current plans to analyze Hurricane Irma, but she is working on an analysis of Harvey, and expects to have results in the next few weeks.

Scientists have had strong evidence for decades that fossil fuel emissions are increasing average global temperatures, and they have long expected that this warming would trigger extreme weather events. But until recently, they were only able to predict general trends in the frequency of extreme events, so most have shied away from linking climate change to specific disasters.

The first study tying a weather event to climate change didn't come out until 2004, making the field of weather event attribution less than 15 years old.

The field has grown quickly since then, thanks largely to improvements in climate models. Now, said Cullen, scientists can conduct robust analyses of certain types of events, including heat waves, cold snaps and droughts. Complicated phenomena like hurricanes are more difficult, but Cullen said that if researchers focus just on heavy rainfall rather than the storm as a whole, they can get a good idea of how climate change contributed. A consensus study published last year by the National Academy of Sciences put it bluntly:

"In the past, a typical climate scientist’s response to questions about climate change’s role in any given extreme weather event was, 'We cannot attribute any single event to climate change.' The science has advanced to the point that this is no longer true as an unqualified blanket statement."

Climate science in court

Courts have already used science to influence climate policies around the world. For example, in 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Environmental Protection Agency has the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions as a form of air pollution, based on evidence that such emissions were changing Earth's climate. In 2015, a court in the Netherlands ruled that the Dutch government must adopt stricter goals to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions, and a Pakistani farmer successfully sued his government for failing to implement its own climate policy framework, leading to the creation of a new court-ordered climate change commission in Pakistan. Other significant cases are still in progress, including one by a group of American youths who are suing the U.S. government on the grounds that U.S. climate policies violate their rights to life, liberty and property.

Climate science is increasingly making its way into lower profile cases as well, according to an analysis published last week in the journal Science. The researchers looked at more than 800 U.S. cases involving climate change or coal-fired power plants between 1990 and 2016, and found a dramatic rise in both the number of climate cases and the proportion that relied on scientific evidence, according to first author Sabrina McCormick, a sociologist at George Washington University in Washington. McCormick and her co-authors reported no conflicts of interest with respect to the new research.

So far, the climate science used in courts has focused mostly on overall trends and gradual processes such as sea level rise, said Michael Burger, executive director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in New York, who said he has no financial stake in climate change litigation.

But it's the extreme events that pose the greatest threat to human health, according to Jonathan Patz, director of the Global Health Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a former lead author of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In addition to causing obvious, immediate dangers such as drowning in a flood, extreme events can leave people without food and shelter, expose them to toxic chemical spills and facilitate the spread of disease. One of the greatest health threats from flooding comes after the waters recede, when people return to homes that may be full of toxic mold, said Patz. Extreme events also carry a heavy financial burden, causing billions of dollars in losses to property, business and tourism.

Scientists have long predicted that climate change would expose more people to such risks. But until recently, it was difficult to point to specific people who had been harmed by climate change, according to Patz. He said as much in 2007, when lawyers consulted him about the landmark case that led to the EPA regulating greenhouse gas emissions.

"I was on the fence back then," said Patz. At the time, he told the lawyers that while climate change was a major threat to public health, "it's going to be really hard to look at the cause and effect." While Patz has advised lawyers on climate cases, he said he has never been compensated for such consultations beyond travel reimbursements.

Now, said Patz, the causal chains are much easier to trace, thanks to weather attribution research of the kind Cullen's team conducts. And that could be important in court, since it could allow people harmed by a disaster to tie their specific injuries to climate change, thus giving them standing to sue governments, agencies or companies over fossil fuel policies and practices.

The ability to link weather events to climate change could also strengthen plaintiffs' arguments that a disaster was foreseeable, according to Lindene Patton, a Washington-based lawyer at Earth and Water Law, LLC. Forseeability is key to determining whether someone has been negligent by, say, leaving toxic waste where it can wash away, or building infrastructure that collapses in a flood. In a commentary in Nature Geoscience last month, Patton and several other lawyers argued that weather attribution science is now robust enough to be important in court and they laid out implications for planners and engineers who want to avoid being sued. Patton said that she has not participated in cases linked directly to climate change in recent years.

Weather attribution research could make a difference in negligence lawsuits in the wake of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, although of course we won't know until the results of the attribution analyses are in, according to Patton. The idea would be that although companies or government agencies may have prepared adequately for certain risks, they could have failed to account for the increased risk due to climate change.

Police and emergency workers have already sued a chemical company for negligence, following a flood-triggered explosion that injured people trying to respond to the disaster. And while Michael Burger of the Sabin Center is reluctant to predict future lawsuits, he does see the potential for more hurricane-related litigation, particularly around facilities leaking toxic pollution.

Burger isn't sure whether extreme event attribution science is strong enough yet to stand up in court, but his team is in the middle of an in-depth analysis to answer just that question. Cullen, for her part, thinks her research is ready for legal applications. She hopes it can make a difference, both in the courtroom and beyond.

"I think as scientists, we have a responsibility to help society understand risk," she said. "The last thing we want to do is prepare for the storm of yesterday, when we know, in fact, that the risk is changing."