Thousands of Hours of Newly Released Audio Tell the Backstage Story of Apollo 11 Moon Mission

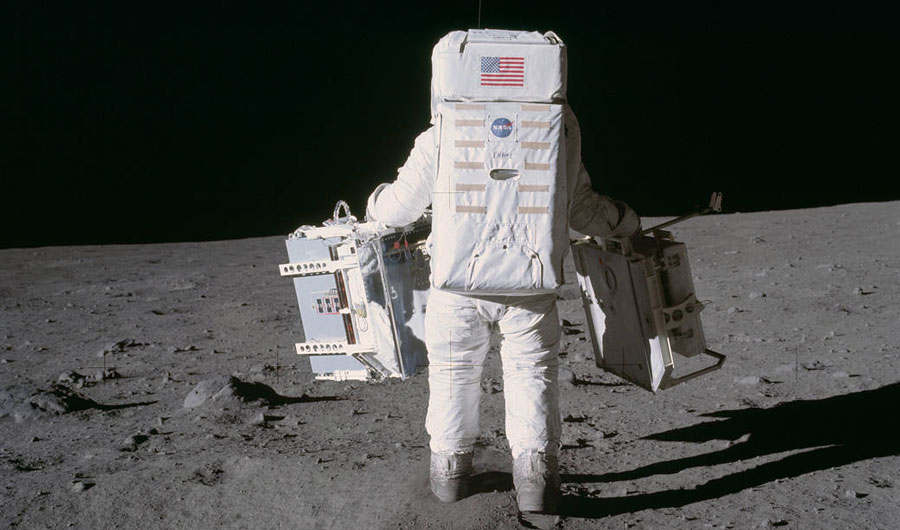

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin carrying two components of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package during the Apollo 11 mission.

NASA

(Inside Science) -- On July 20, 1969, just before 11 p.m. Eastern time, Neil Armstrong planted the first human footprints on another world. It was a defining moment in a journey that had transfixed the planet.

A few days earlier, Armstrong and his fellow astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins had blasted skyward atop a 6.2 million-pound rocket, embarking on an epic eight-day trip to the moon and back that included a brief stay in the moon's Sea of Tranquility and ended with a splash into the Pacific Ocean.

During the entire tense mission, NASA recorded thousands of hours of audio communications between the astronauts, mission control and backroom support staff.

For decades, most of these tapes sat in storage. Only a fraction of the audio -- like Armstrong’s famous first words from the moon -- were ever released to the public. But now a years-long project to digitize and process the audio from the tapes has given this historic record new life.

The original impetus for the project was simply to find a large set of audio data to help develop tools for assessing how teams work together.

But for NASA buffs, students, and the public, the audio also offers an opportunity to relive these historic moments from a new perspective.

“I think that Apollo 11 is one of the biggest engineering accomplishments in human history,” said Greg Wiseman, an audio engineer at NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston involved in the project. “Landing on the moon wasn't just Neil Armstrong. It was an entire team of people working together to make it happen, and all of this audio is their side of the story.”

Only one machine in the world to play the tapes

After the Apollo missions ended, most of the audio tapes eventually made their way to the National Archives and Records Administration building in College Park, Maryland. The first step in the project was to find them.

“There were lots of emails from me to the NARA reps trying to figure out where these tapes are,” Wiseman said. The process reminded him of the last scene in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, where the audience sees the ark being stored away in a gigantic warehouse. “It could be difficult to locate a few boxes of tapes in that vast ocean of historical treasures,” Wiseman wrote in a later email.

The hunt began after John Hansen, an electrical engineering researcher at the University of Texas at Dallas, contacted NASA with a request for audio. Hansen was leading a project to develop speech technology to parse long audio recordings of groups solving problems and was looking for test data. The Apollo audio fit the bill, but the next challenge was presented by mid-20th-century analog technology.

The existing tapes could be played only on a machine called a SoundScriber, a big beige and green contraption complete with vacuum tubes. NASA had two machines, but the first was cannibalized for parts to make the second one run.

“There is literally just one machine left on the planet that can decode [the audio]” said Abhijeet Sangwan, a researcher at UT Dallas who also worked on the project.

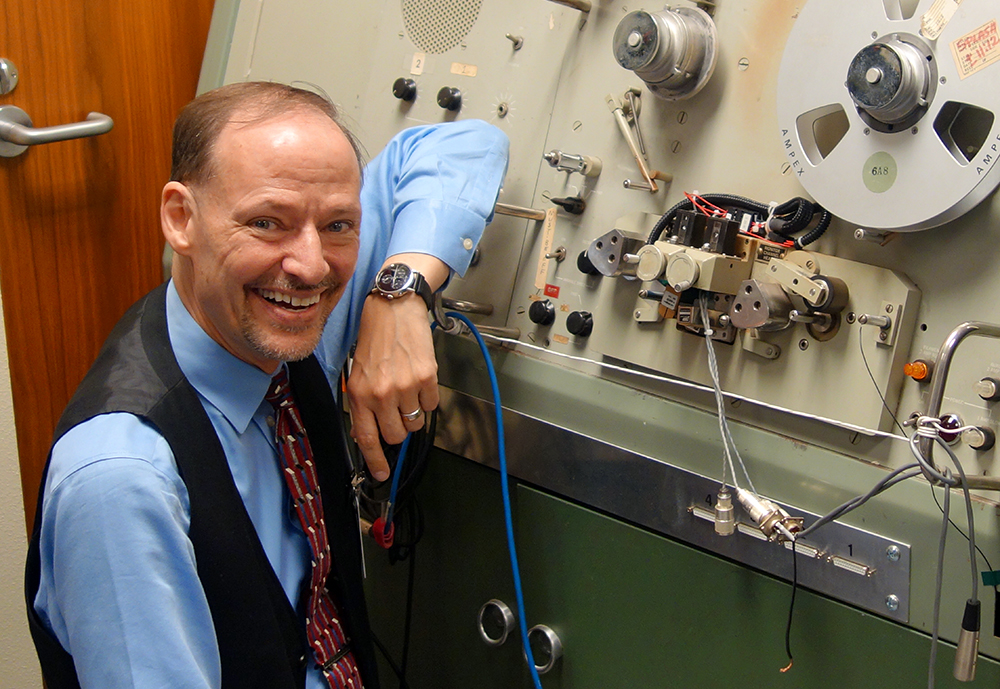

John Hansen posing next to the SoundScriber machine, the only device that could play the analog tapes from the Apollo missions.

Credit: The University of Texas at Dallas

NASA tracked down a retired technician to help refurbish the machine and Hansen and his team designed and installed a custom read head. NASA had recorded the mission audio on 30-track tapes and the team needed to play all 30 tracks at once to minimize the time required to digitize them, as well as to avoid damaging the almost 50-year-old tapes by playing them over and over.

Once everything was operational, an undergraduate student ran the machine five days a week for months in order to capture all the audio from the Apollo 11 tapes, as well as most of the tapes from Apollo 13, Apollo 1 and the earlier Gemini 8. (The audio from Apollos 1 and 13 and Gemini 8 has not yet been cleared for release, and the researchers are now trying to get support to digitize the remaining Apollo 13 data.)

A resource for the speech processing community

With 19,000 hours of newly digitized data in hand, Hansen and his team began the complex task of analyzing it.

They built software programs to detect speech in the recordings, identify the speakers, group the audio by speaker turns, transcribe it, and detect positive and negative sentiments. Most state-of-the-art speech recognition algorithms are designed for short, transactional statements, like asking Siri for the weather forecast, so the sheer volume and complexity of the NASA tapes presented unique challenges.

The recordings had long stretches of silence, and when people were talking, the channels were often noisy or had the air-to-ground communications -- the main mission broadcast -- playing in the background. Plus, the engineers spoke a space mission-specific dialect that contained words absent from the dictionary. Hansen and his team spent about six months researching and collecting all the acronyms used by NASA, specifically for improving automatic speech recognition performance, he said.

After honing the algorithms, the researchers set up three large computing clusters on the UT Dallas campus and processed data continually for about seven months. The transcripts they produced range in accuracy from about 60 to 97 percent -- not good enough to get a true historical record of what was said, but valuable to help analyze sentiments, and when combined with speaker identity, understand the engagement and problem-solving processes of the team members.

The researchers hope the solutions they developed could also be applied to tasks such as monitoring the team dynamics of astronauts during a lengthy and stressful trip to Mars. Closer to home, the techniques could help analyze and improve the performance of large teams who rely on real-time audio communication, such as emergency response units or the military -- or even help analyze something more mundane, like a conference call.

The data is an important resource for the speech processing community, Hansen said, because it is both long and naturalistic. He advertised the data at an international conference on the science and technology of spoken language processing this September and encouraged researchers to use it to develop better tools for key challenges in the field.

But another important mission of the project is sharing the data with the public.

The heroes behind the heroes

In advance of next summer's 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, NASA has cleared the Apollo 11 audio for public release. Student design teams from UT Dallas built a website, Explore Apollo, where the public can listen to some key moments from the missions.

NASA has also uploaded the audio to archive.org, a publicly accessible internet library of cultural artifacts, and it has been shared with filmmakers who are working on new ways to tell the moon landing story. Many retrospective projects on the Apollo 11 mission, such as the recently released movie First Man, focus on the heroics of the astronauts who risked their lives. But there were hundreds of others whose collective work was equally vital, including the more than 600 voices from the tapes.

“These are the heroes behind the heroes,” Hansen said.

Inside the Launch Control Center, personnel watch as the Saturn V rocket carrying the Apollo 11 astronauts lifts off.

Credit: NASA

Ben Feist, a software engineer currently based in Canada, is using the audio to build an interactive website where the public can explore the whole Apollo 11 mission timeline. It will be similar to Apollo17.org, a site he built to showcase a vast array of audio, video and photos from NASA’s last mission to the moon. However, the backroom audio channels from the newly digitized Apollo 11 tapes offer a new type of behind-the-scenes perspective.

For example, when Armstrong first stepped on the moon he was supposed to grab some surface material -- called the contingency sample -- right away, in case the mission had to be aborted. But as he began to explore and take pictures, he did not reach for any material. There was backroom discussion about whether he was going to pick up the sample, and the engineers seemed reluctant to remind him over a mission broadcast that was being streamed live to the media, Feist said. Finally, the CAPCOM -- the person designated to speak to the astronauts from mission control -- solved the problem by telling Armstrong that they see him retrieving the contingency sample, subtly signaling to the astronaut to do so, Feist explained.

Feist has processed the audio to remove a flutter and other distortions, and plans to give the cleaned-up version to the National Archives when the project is finished.

Because the tapes were recording continuously, they captured moments when NASA staff took breaks to chat with each other or call friends and family. “They were people just like us,” Feist said. They would sometimes phone home to say they would be late, or complain about overtime.

But when the engineers were on duty, a cool professionalism came through, according to many of the researchers who have listened to sections of the audio.

“NASA engineers and scientists are just the utmost professional people,” Hansen said. “There are things that would rattle other people and they are just as calm as you can be.”

“They are extremely focused and very calm,” echoed Wiseman.

It was left to the president of the United States, Richard Nixon, to gush. Upon greeting the Apollo 11 crew after they returned to Earth, he exclaimed, “This is the greatest week in the history of the world since Creation.”

And now a much more complete record of that exhilarating and exhausting week will be preserved in digital format for generations to come.